Debt

What does it look like for churches to act faithfully in the current tumultuous political crisis? Prophetic witness and speaking up for justice matters; acting faithfully goes hand in hand with speaking faithfully. Whatever policy priorities churches focus on, they should always look to go deeper into solidarity with those in need in their communities — especially marginalized people who are in danger due to unjust government actions.

Solidarity isn’t affection. Solidarity is, instead, a recognition that our destinies are intertwined because of our common humanity. As Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

FOR SOME REASON, conversations about economics and the church are rare these days — even though scripture includes more than 2,000 verses on poverty, such as laws in the Hebrew Bible on debt, labor, and land ownership. In the gospels, Jesus had many conversations with people about their relationship to money.

Our daily lives wade in the waters of economics, even in the most ordinary ways. When I brushed my teeth this morning, for instance, I used a brand-name electric toothbrush and a brand-name toothpaste, one that claims to be gentle on tooth enamel. After leaving my apartment, I gazed ahead to the street corner, where a man with a familiar face extended his hand in need to passersby. On the streets of New York City, the human cost of economic insecurity is painfully evident. I made my way eastbound toward Park Avenue; the potholes had me pondering how my hood is often overlooked in the city’s infrastructure budget. Yet, somehow, new “affordable” luxury apartments pop up, seemingly out of nowhere; I sometimes wonder if these buildings just appear overnight, ready-made. I’m also reminded that our local community board, through its land use committee, had some say in these new developments.

First Presbyterian, a congregation in the Presbyterian Church (USA) denomination, is one of many across the country raising money through the nonprofit RIP Medical Debt to buy and forgive medical debts owed by people who can’t afford to pay them back. The church hopes to raise $50,000 as one of two mission components to its capital campaign — enough to forgive $5 million in medical debt.

Jubilee is appearing all around us amid the coronavirus pandemic.

THE HOLY SPIRIT has a starring role leading up to Pentecost, not only on the day itself. Jesus prepares the apostles to receive “another Advocate.” Other readings jump forward to what occurs when disciples are filled with the Holy Spirit. This could be an unusual level of holiness meant for a few, but it sounds like a holiness to which we can all aspire. Stephen and the apostles were granted heavenly visions or the ability to speak new languages. The challenge for believers today is to recognize when the Spirit of truth “comes upon” us.

A clue might be found in how Jesus describes the approach of the Holy Spirit to the disciples (Acts 1:8): This verb (eperchomai) conveys the sense of moving from a transcendent position toward one who is less powerful. The writer of Luke-Acts also uses the verb in this way when Gabriel answers Mary’s question about how it could be that she will bear the Messiah.

Mary, the apostles, Stephen, and others weren’t powerful to begin with. It is the Spirit who empowered them, who made risky discipleship possible. And the “signs and wonders” (Acts 5:12) that flow from being full of the Spirit aren’t always spectacular. We could be filled with the Spirit when we turn a vacant lot into a community garden. Or when we register new voters. Or furnish a home for a family seeking asylum. We don’t need a certain level of education, status, or holiness to live into Jesus’ promise that his followers can receive power to do great works (John 14:12).

May 3

Churches ‘Heal’ Debt

Acts 2:42-47; Psalm 23; 1 Peter 2:19-25; John 10:1-10

AMID “SIGNS AND wonders” by the apostles, Acts 2 describes how early Jesus followers provided for each other by selling off possessions and goods, praying together, sharing meals, and holding property in common. That may seem an impossible ideal.

But sharing resources beyond our individual household can be creative while supporting communal stability and security. The early Christians intertwined worship with economic relationships and forged bonds of community. Congregations can do this in diverse ways.

Several Chicago-area congregations have helped to raise money for canceling medical debt through a nonprofit organization called RIP Medical Debt. RIP uses the same method as debt collectors—it buys debt in bulk from brokers at a deep discount—except RIP then collects donations to clear the debt. Individual contributions as small as 50 cents or a dollar from people in the pews together wiped out thousands of dollars of medical debt, freeing a family. Members of the participating congregations rejoiced in worship that they could relieve financial stress, even while many of them also had such debt.

IF JESUS BROUGHT good news to the poor today, it might look like one of Shaunna Burns’ videos.

Burns is an honest-to-God evangelist on TikTok, the fast-growing, Chinese-owned, short-form video-sharing social network. Translate Jesus’ “brood of vipers” and “whitewashed tombs” into f-bombs and salty vernacular and you get Burns’ practical “good news” that’s changing lives.

A former debt collector, Burns knows all about the shady practices of collection agencies. But she didn’t start her 60-second “debt pro tips” on TikTok until she got a call herself from a collection agency harassing her for her daughter’s medical bills.

“Hey, guys. So, here’s some quick debt-collection pro tips,” North Carolina-based Burns starts in her first video in December. She then instructs the uninformed: It’s illegal for debt collectors to call outside of certain hours. Medical debt has a statute of limitations—usually three to six years—that varies by state. Always ask a collector for a copy of your original signed invoice.

CREDIT CARD DEBT plagues our communities. The average U.S. household carries a balance of $6,929 at the end of the month. And if you miss a payment, interest may jump from 15 percent to more than 20 percent.

Credit cards are part of a predatory industry with a history of racial bias. Many people can afford only the minimum monthly payment, barely making a dent in the principal —just as the system was designed.

About 10 years ago at Circle of Hope, my church in Philadelphia, we began experimenting with “credit card debt annihilation.” Our team’s motto came from Romans 13, where the apostle Paul urged believers to “owe no one anything,” except love.

Even many within the Christian universities said they grew too fast, did not allocate money well — or both.

Faith-based agencies that resettle refugees in America stand to gain more than a clear conscience if the United States — after what is expected to be a fierce debate in Congress — accepts a proposed 10,000 Syrian refugees next year.

More refugees also means more revenue for the agencies’ little-known debt collection operations, which bring in upwards of $5 million a year in commissions as resettled refugees repay loans for their travel costs. All nine resettlement agencies charge the same going rate as private-sector debt collectors: 25 percent of all they recoup for the government.

This debt collection practice is coming under increased scrutiny as agencies occupy a growing stage in the public square, where they argue America has a moral obligation to resettle thousands of at-risk Syrian refugees. Some observers say the call to moral action rings hollow when these agencies stand to benefit financially.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio released Nov. 9 the first comprehensive study of the practice of charging people in jail for their time there, also known as “pay-to-stay” policies, reports the BBC.

The study revealed that some inmates have debts of up to $35,000, although the BBC found evidence that one man in Marion, Ohio owes $50,000 in pay-to-stay debt.

Pay-to-stay is not limited to the state of Ohio, however. With the exceptions of Hawaii and the District of Columbia, every state in the U.S. has a law authorizing the practice.

While President Obama's "Student Aid Bill of Rights" is a prudent and necessary step towards aiding college students, his announcement comes late for the seven million borrowers already indentured to their education debt. In "Forgive Us Our Debts" (Sojourners, April 2015), Virginia Gilbert investigates the cause-and-effect battle of education debt and the way it is hindering a generation of college students. How big is the student debt burden? See below for the poor report card reveal.

On Feb. 8, civil rights attorneys sued the city of Ferguson, Mo ., over the practice of jailing people for failure to pay fines for traffic tickets and other minor, non-criminal offenses.

And to this I say: It’s about time.

Growing up with an attorney father — a “yellow dog Democrat” one at that — who often took on poor clients in return for yard work and other non-cash payments, I heard early and often about the unfair — and illegal — practice of debtors’ prison. A poor person could not be jailed for failure to pay a fine, my father told me. I trusted his words were true.

So imagine my surprise when at the age of 18, I was arrested for unpaid traffic fines.

At that time I was a stay-at-home mom, trapped in a too-early marriage I would one day leave. My son was probably 6 months old. When the knock came at my door and I saw a police officer standing outside, I didn’t hesitate to answer.

The officer confirmed my identity and told me I was under arrest for failure to pay traffic tickets I had received for driving an unregistered vehicle.

I know that I should have paid the registration. Once ticketed, I know I should have worked out a payment plan. I know I should have taken responsibility for my illegal actions.

But I was young, inexperienced with the system, and very, very poor. Too poor to keep up with even the most modest of payment plans.

The contemporary fast-paced, capitalistic, U.S. free market society has lost the traditional commitments to and comprehension of ‘church.’ Our parents and grandparents understood church as a community to which they belonged. Church was a place where many aspects of social life happened. The pastor was hired by the church people to care for and nurture the community, both individually and collectively. People looked to the pastor for spiritual inspiration, ethical guidance, sound counsel, and pastoral care. The pastor was an extended member of the family and people were happy to make a personal financial contribution to pay the pastor's salary and to keep the church building in repair. Somewhere along the line our society ‘outgrew’ this version of church.

A recent article in The Atlantic titled "Higher Calling, Lower Wages: The Vanishing of the Middle-Class Clergy" laments the shift away from the traditional model of financing church and clergy as well as the increased costs for training clergy. The average Master of Divinity student (the degree for pastoral training) graduates with tens of thousands of dollars in student loans — sometimes entering into the six-digit category. According to the U.S. department of labor, the median wage for a pastor is $43,800 — not a salary that lends itself to paying off high-end loans.

RECENT YEARS HAVE witnessed a deluge of headlines such as “Jobs Become More Elusive for Recent College Grads” from Reuters and “For Recent College Grads, Recessions Equal Underemployment” from Inside Higher Ed—headlines that make even the most hearty college students experience heart palpitations. According to a 2014 analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “the underemployment rate for 22-year-olds is about 56 percent, indicating that more than half of the people just graduating end up working in jobs that do not require a degree,” jobs for which they are overqualified.

To put this into perspective: I am a 22-year-old senior at a private Christian university. Of my close friends who graduated in the last year or two, the only ones who were able to find jobs in their fields were education and nursing majors.

Don’t get me wrong, I love liberal arts and feel grateful for the critical thinking skills, study-abroad opportunities, and philosophical discussions that attending a liberal arts school has afforded me. But learning in the same analysis that “only 40-to-45 percent of recent college graduates majoring in communications, liberal arts, business, and social sciences were working in jobs that required a degree” is troubling at best.

In addition, seven out of 10 college seniors are graduating with an average of $29,400 in debt due to rising tuition costs for an undergraduate education. The National Center for Labor Statistics found that in the past decade, the cost of “tuition, room, and board at public institutions rose 42 percent after adjustment for inflation.” The situation was a bit (though not much) better at colleges in the private not-for-profit group, like my own, where the average price rise was 31 percent.

Debt from college loans makes some men and women postpone joining a religious community, according to a survey of men and women professing final vows in a religious order.

Ten percent of those who professed final vows in 2013 had an average amount of $31,000 in college debt and the average length of delay was two years, according to “New Sisters and Brothers Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2013.” The annual survey was conducted by the Georgetown University-based Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA).

Read the entire survey here.

I’m a big fan of the TV show Mad Men, which takes place in the midst of the Madison Avenue advertising agencies back in the ’60s and ’70s. Sure, I enjoy the drama and the “cool factor” of Don Draper and his cavalier ad team. But for me, the most fascinating part is all of the cultural norms of the time that seem fairly shocking now, only a few decades later.

Of course, there’s all the drinking and smoking in the office, but beyond that, the way that non-Anglo employees and the women in the workplace are treated would today be grounds for a lawsuit, if not public shaming for such brazen chauvinism. The thing that’s hard to remember is that, although we see such behavior as morally offensive today, it was simply normal back then.

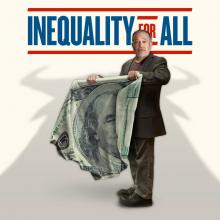

Robert Reich pulls up in his silver Mini Cooper, quipping that he and his car are in proportion to each other. Reich, former Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration, identifies himself with the underdog, the little man.

His new movie, Inequality for All, looks into the effects of wealth inequality in the United States. Throughout this semi-autobiographical documentary, Reich consistently leans on his self-deprecating sense of humor by poking fun at his own physical stature; he’s 4’10 ½’’ tall. The jokes, however, do lead back to the heavier issue at hand – the American worker is getting squeezed out of the middle class.

AS FIGHTS ABOUT the budget and other economic issues are again riveting the nation’s capital, the rest of the country yawns. Possible government shutdowns, threats to default on our nation’s debt, and proposals to decimate food assistance for struggling Americans seem to be business as usual in Washington, D.C. These budget battles have become so frequent that it is tempting to dismiss it all as political posturing. But that would be a mistake.

The biggest challenge facing Congress should be a non-issue. The debt ceiling is simply the amount of debt the U.S. is legally allowed to hold. It is about paying off the bills that Congress has already incurred from past appropriations—not about giving permission for new government spending, as many people falsely assume. Congress has raised it nearly 100 times since the end of World War II, but it only recently became a political football. Because the consequences of not raising the debt ceiling and defaulting on our nation’s obligations could be catastrophic, some leaders have tried to leverage it for political gain. After the country came close enough to a default in 2011 to receive a credit downgrade, President Obama has responsibly refused to negotiate over raising it. His assumption is that GOP leaders in Congress wouldn’t throw the economy off the cliff for their own political gain. The American people are left watching this game of chicken and hoping somebody blinks.

While this is clearly a partisan game, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The U.S. has always honored its debts. Should the country default, the market turmoil and long-term effects could be catastrophic for the global economy. Domestically, it could throw the U.S. back into recession.

Debt, multitudes think, is bad. It could be good, by helping more people manage the energy of money. The Lord’s Prayer helps the confusion along: some pray to be forgiven debts, others to be forgiven trespasses. Good debt does not trespass. Bad debt is most often done by banks, and trespasses inside people, insidiously, and shames them. Religious institutions help the shame along by mispraying the Lord’s Prayer.

Debt might be good. In his book on Debt: The First 5000 years, David Graeber opens with a story. The story is paradigmatic. A woman tells a man the story about a person who is “under water.” “But, shouldn’t she have to pay her debt?” Should. Have. Pay. Debt. Those four words go together. They mispray the Lord’s prayer. Instead we might pray, “forgive the banks their trespasses into our souls first and then our pocketbooks.”