daniel berrigan

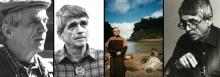

As part of the Catonsville Nine, the rebel priest Daniel Berrigan joined eight other Catholic activists in setting fire to hundreds of draft files with homemade napalm. It was 1968 and he was protesting the Vietnam War. The way he evaded prison was perhaps as memorable as the crime he committed.

FOUR DECADES AGO, when I was a young editor at Sojourners, Daniel Berrigan wrote a poem for a special edition of the magazine. The note accompanying it read: “Here’s the poem—my first on a word processor. Seems a bit jumbled. Might have got a food processor by mistake.”

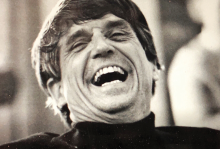

Berrigan has been described often as poet, prophet, and priest. The note reveals another alliterative trio that marked his life: humor, humility, and hospitality. Though I never saw him use a food processor, over the years I enjoyed several delectable dinners he whipped up in his apartment in New York City and his cottage on Block Island, accompanied by his droll wit. Berrigan was engaged in an unflinching, lifelong facedown with the world—observing its worst inhumanities and fully understanding its unlimited capacities for destruction—but he also knew how to be tickled by joy.

Bill Wylie-Kellermann is among those in Berrigan’s close circle who feasted regularly at his table, drawing sustenance from the food, lively conversation, and prophetic insights. Celebrant’s Flame: Daniel Berrigan in Memory and Reflection (Cascade Books) is Wylie-Kellermann’s moving tribute to the man who was first his professor, then his mentor, and ultimately his beloved friend. It is a treasure trove of poems and letters, sermons and speeches, reflections and court testimonies, even a seminary paper—a patchwork sewn into a beautiful whole.

Unsung Belonging

Serenade is a collaborative album dedicated to LGBTQIA+ youth of faith. Produced by Gretta and Kyle Miller of the band Tow’rs, this multigenre and multiartist project explores the “hope and heartbreak” of living as a queer person of faith. Beloved Arise Media.

WHEN DANIEL and Philip Berrigan, A.J. Muste, John Howard Yoder, and a handful of Catholic radicals gathered in 1964 with Thomas Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky for a retreat concerning the spiritual roots of protest, the intercessions of that meeting, I am convinced, not only seeded a movement but summoned my vocation.

Four years later when Daniel and Phil Berrigan and seven others entered the draft board in Catonsville, Md., removed 1A files and burned them with homemade napalm, those ashes too would eventually anoint my pastoral calling. October marks the 50th anniversary of the trial of the Catonsville Nine. Released in February 1973 after 18 months in the federal penitentiary at Danbury, Conn., Daniel Berrigan came to New York and taught the Apocalypse of John when I was a student at Union Seminary. Full disclosure: He became to me not merely teacher, but mentor and friend.

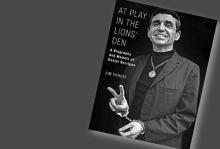

In the year following Dan’s death (April 30, 2016), Jim Forest undertook the heroic literary effort of writing At Play in the Lions’ Den. Perhaps he had a running start. Three things of note up front. One is that Forest’s own life is inextricably tangled with Berrigan’s. He was, for example, editor of The Catholic Worker when Dan first appeared there, was part of the 1964 retreat with Merton, and responded to Catonsville by joining others in a draft board raid in Milwaukee within the year. So, like the Acts of the Apostles, there are whole sections of this book written in the first-person voice. Or betimes, Forest just peeks from behind the elegantly researched narrative to lend a knowing detail. This is a risky wire act. Don’t fall into self-aggrandizement (his genuine modesty saves him that) or the net of hagiography. And best to name this from the start, in the subtitle: “biography” and “memoir,” a difficult art Forest has mastered.

"We have yet to experience resurrection, which I translate: the hope that hopes on…"

On April 30, 2016, Catholic peacemaker and activist Daniel Berrigan entered life eternal. He was a teacher and friend to many in the Sojourners community. Read more reflections on Dan's life and legacy in the August 2016 issue.

"VIOLENCE ONLY EXISTS with the help of the lie!”

With these words Father Daniel Berrigan and I sealed our fate. It was summer 1995. August 6. We’d been invited to read at the Washington National Cathedral’s service commemorating the 50th year since the U.S. used atomic weapons on civilians in Japan.

The cathedral was full. I was supposed to read an adaptation from Thomas Merton’s scathing indictment of U.S. militarism, the poem “Original Child Bomb.” Dan was slated to read from Soviet-resister Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Nobel Prize lecture and from Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish priest who exchanged his life for a fellow prisoner in Auschwitz.

Minutes before the liturgy began, a member of the cathedral staff told us there was a change in the readings. Thomas Merton was too controversial; I should read from Deuteronomy. Dan should also read from scripture instead of from Solzhenitsyn and Kolbe.

On April 30, 2016, Catholic peacemaker and activist Daniel Berrigan entered life eternal. He was a teacher and friend to many in the Sojourners community. Read more reflections on Dan's life and legacy in the August 2016 issue.

I ONCE HAD a conversation with Dan about his death. We were talking late into the night at the Block Island hermitage that his friends William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne had built for him while he was two years in Danbury federal prison, a consequence of the 1968 Catonsville draft board action. He had by then foresworn scotch, on doctor’s orders, so I was being introduced to Manhattans dry, which were somehow allowed. The place suited the topic. On the wall above us was an exorcism poem that he’d hand-lettered in a style familiar to Catholic Worker and resistance houses across the country.

I’m certain it was I who broached the topic. When we met in the early ’70s, it was in the wake of notorious assassinations: Medgar Evers and Viola Liuzzo, the Panthers, Malcolm, King, the Kennedys. There was a certain youthful grandiosity in imagining that he or others who were such troublesome peacemakers would be similarly targeted. I braced my heart. I told him so. (Then he turns around and lives, thanks be, to 94!)

On April 30, 2016, Catholic peacemaker and activist Daniel Berrigan entered life eternal. He was a teacher and friend to many in the Sojourners community. The following article is adapted from the homily Steve Kelly gave at Dan's May 6 funeral Mass in New York City. Read more reflections on Dan's life and legacy in the August 2016 issue.

IN THE STORY OF LAZARUS, told in John’s gospel, seemingly Jesus arrives too late. Humanity, doomed like Lazarus, is sealed under two tons of stone. Is this then an inspired picture of how God sees us? Humanity sealed up in death? Death taunting Jesus until Jesus has a visceral reaction? The hand of death moves the chess piece toward checkmate.

The complexity of the lie goes: “Once you are dead, once afraid, how will God guide you?” If afraid, how can one obey the guidance, dependence on the one who sent him?

“Greater love has no one than to lay down one’s life for a friend.” So God does know what it’s like to encounter death’s whiplash version. Always, everywhere, each time, each encounter, risks are included.

Jesus went the distance in this anguishing scene. To see him at work is to see life itself overcoming death, because he, as a human being, cooperated, obeyed the guidance of the one who sent him. He loved, he lays down his life.

Now there is a different moral power in town. God is going to crack death’s veneer, a chink in the armor. Through Jesus’ obedience, the crumbling begins, and the hidden, insipid hold of death is broken.

WHEN I WAS BORN—the first child of Dan Berrigan’s brother Phil and Elizabeth McAlister—my uncle sent my parents a sheaf of poetry. On it, he wrote a note: “Dears, I send these with trepidation. They are uneven; but then so is life, no? Love, Daniel.”

My parents put the dozen or so poems in a book and gave them to me on my eighth birthday with their own note: “We don’t expect you to understand all of them yet but you can now begin to read and grow with them.” Yet. Right. I am now 34 years older than I was when I first opened the little red bound book of handwritten poems, and I don’t understand them any better.

But now that my dearest Unka has passed from this world, I hold on tight to this collection and try really hard to understand. It is going to be tough. The poems are full of words the dictionary either fails to define or further confuses—supramundane, Blake’s child, Dante’s paradise (what are boys from middle school doing in Unka’s poetry?), “the bodhisattva is neither stuporous nor sleek / he is crucified.”

Fragments of these poems cycle through my head all the time, a sort of back rhythm to daily life, especially when that daily life was graced with Unka.

Uncle Dan and I would walk—down New York City’s Broadway and through Riverside Park. He breathed in such love for the natural world, even amid the Upper West Side’s hustles and bumps. He saw everything, and found the beauty that was there. The only people that made him mad were delivery men riding bikes on the sidewalks—he had been knocked down once by them and he worried about the elderly—and people who lost themselves in their phones.

WHEN WE LOSE a Christian peacemaker such as Daniel Berrigan, as we did in April, it gets very personal for many of us. Berrigan shaped and motivated a Catholic peace movement that became a fundamental and foundational influence on Sojourners and on me personally.

During my early years at Michigan State University, friends were drafted, others feared they would be next, and the Vietnam War consumed the attention of an entire generation. Then I learned about Daniel and Philip Berrigan and the small group of Christian protesters they were inciting. They were the only Christians I had heard about who were against the war in Vietnam.

Here were some Christians who were saying and doing what I thought the gospel said—and what nobody in my white evangelical world was saying or doing. The witness of the Berrigans helped keep my hope for faith from dying altogether. African-American Christians fighting for justice and that “Berrigan handful” of Christians fighting for peace paved the way for my return to faith.

Daniel and Philip Berrigan rose to national prominence after they and seven others burned 378 draft files with homemade napalm taken from a draft-board office in Catonsville, Md., on May 17, 1968. The result was jail sentences for the group and, eventually, Daniel’s play “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine.”

For 30 years, the Berrigan brothers led the nonviolent charge against war, poverty, and racial injustice, writing letters to each other and to other loved ones throughout their years of activism. Their work took them all over the country and world (including to a 1985 Sojourners Peace Pentecost celebration in Washington, D.C.), and these letters catalog their dreams, plans, worries, and prayers during their travels. From news clippings, poems, and reports about trials, to birthday greetings and responses to political elections, the Berrigan brothers expressed honesty, faithfulness, and love for one another and the world.

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan was regularly challenged during his life by skeptics and newcomers to the cause of peacemaking to show the results of the thankless work he had undertaken. He regularly responded that God calls us to faithfulness, not success.

The name Berrigan helped keep the possibility of coming back to my Christian aith alive. Just like the black churches that took me in, here were some Christians who were saying and doing what I thought the gospel said that nobody in my white evangelical world was. I believe the witness of the Berrigans literally helped keep my hope for faith from dying altogether.

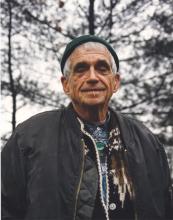

Dan Berrigan published more than 50 books of poetry, essays, journals, and Scripture commentaries, as well as an award winning play, The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, in his remarkable life, but he was most known for burning draft files with homemade napalm along with his brother Philip and eight others on May 17, 1968, in Catonsville, Md., igniting widespread national protest against the Vietnam War, including increased opposition from religious communities. He was the first U.S. priest ever arrested in protest of war, at the national mobilization against the Vietnam War at the Pentagon in October 1967. He was arrested hundreds of times since then in protests against war and nuclear weapons, spent two years of his life in prison, and was repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The Rev. Daniel Berrigan, a Jesuit priest and herald of the Catholic social justice movement whose name — along with his late brother, Philip, also a priest — became synonymous with anti-war activism in the Vietnam era, has died.

He was 94 when he passed away on April 30 and had been living at the Jesuit infirmary at Fordham University in the Bronx.

THE FONDEST memories I have of Kathy Kelly are of her singing. It’s safe to say that her three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize were not for her voice, which is sometimes sweet but often a touch out of key. At times I’ve imagined her feeling briefly self-conscious about this, but that passes. The song remains, and I am again reminded of just how deeply this woman can move me.

In spring 1999, in a small banquet room at Georgetown University, I first heard Kelly sing and speak about the suffering in Iraq. A crowd of about 200 people had gathered to hear about her work. She had been to Iraq dozens of times to put a human face on the conflict there and to defy the drastic financial and trade embargo that the U.N. Security Council had imposed shortly after Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

She briefly went over the statistics—the deep poverty, the lack of medicines, the estimated half-million children who had died, many due to the U.N. sanctions, enforced in part by a U.S.-led blockade—but she quickly moved on. Statistics weren’t her strength.

Instead she spoke from the heart. Kelly talked about the ordinary Iraqis she had met: the worn women who served her tea and biscuits they could barely afford, the countless kids in threadbare hand-me-downs who ran after her merrily in the street, the tired doctors who broke down crying as they remembered all the children they had lost, the stone-faced parents who accepted her condolences because they didn’t know what else to do.

She also told the story of Zayna, a 7-month-old baby girl who died of malnutrition shortly after Kelly visited her in the hospital.

On December 13, a Tacoma-based jury declared five Disarm Trident Now Plowshares activists "guilty" of trespass, felony damage to federal property, felony injury to property, and felony conspiracy to damage property.