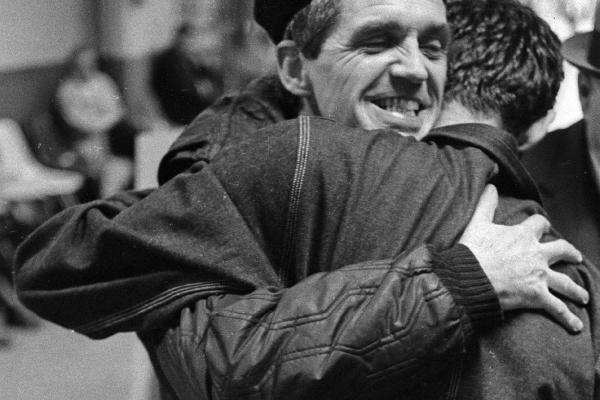

On April 30, 2016, Catholic peacemaker and activist Daniel Berrigan entered life eternal. He was a teacher and friend to many in the Sojourners community. Read more reflections on Dan's life and legacy in the August 2016 issue.

WHEN WE LOSE a Christian peacemaker such as Daniel Berrigan, as we did in April, it gets very personal for many of us. Berrigan shaped and motivated a Catholic peace movement that became a fundamental and foundational influence on Sojourners and on me personally.

During my early years at Michigan State University, friends were drafted, others feared they would be next, and the Vietnam War consumed the attention of an entire generation. Then I learned about Daniel and Philip Berrigan and the small group of Christian protesters they were inciting. They were the only Christians I had heard about who were against the war in Vietnam.

Here were some Christians who were saying and doing what I thought the gospel said—and what nobody in my white evangelical world was saying or doing. The witness of the Berrigans helped keep my hope for faith from dying altogether. African-American Christians fighting for justice and that “Berrigan handful” of Christians fighting for peace paved the way for my return to faith.

Daniel and Philip Berrigan rose to national prominence after they and seven others used homemade napalm to burn 378 draft files taken from a draft-board office in Catonsville, Md., on May 17, 1968. The result was jail sentences for the group and, eventually, Daniel’s play “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine.”

Daniel famously went underground after the sentencing. Life magazine described his August 1970 arrest on Block Island, R.I., where he was hiding at the home of his friend William Stringfellow. “On an ominous morning in August, with a fierce nor’easter blowing up black clouds and spattering rain over the harbor, Daniel Berrigan lay asleep in a manger [a little shed outside the house, which Stringfellow called “Eschaton”] on Block Island, R.I.,” wrote Lee Lockwood in the May 21, 1971, edition of Life. FBI agents, posing as birdwatchers on the island, apprehended Dan and took him off to a facility in Danbury, Conn., to which he had been given a three-year sentence. When Stringfellow was asked about his own potential prosecution for harboring a federal fugitive, he said, “I don’t fear persecution. I know we are in jeopardy, but everyone in this country is in jeopardy.”

The Stringfellow house and Berrigan cottage were to become my primary retreat and only vacation destination in the years to follow, and the place where Dan and I had our most personal conversations—on long walks along the beach or paths around the island, or on his porch overlooking the Atlantic. I remember many a long meal with Bill and Dan, around Bill’s dining room table or at the cottage, for some of the best theological and political conversations of my life. Dan, members of his family, and personal friends came to that cottage for years after Bill died, and it became a sacred space for many of us. I even proposed to my wife, Joy Carroll, on Block Island, and we have taken our two boys there regularly for many years.

Called to be peacemakers

I was always grateful for the way Daniel Berrigan consistently made the connections between peace and justice. In his testimony at the Catonsville trial, he said, “Our apologies, good friends, for the fracture of good order, the burning of paper instead of children, the angering of the orderlies in the front parlor of the charnel house. We could not, so help us God, do otherwise. ... The time is past when good [people] can remain silent, when obedience can segregate [people] from public risk, when the poor can die without defense.”

This is where the vocation of Daniel Berrigan becomes clear. His critics often accused him of disorderliness, creating drama, and causing discomfort—all of which were true. That’s because Dan was not only a priest and poet, he was a prophet, in the biblical tradition of those who caused such trouble on behalf of what they believed God was trying to say to us. It is in that prophetic tradition that Sojourners has tried to stand—and Dan, for all his controversy and confrontational style, has helped us to stand there. Whether we were Catholic or evangelical or anything else, Dan always gave us comfort, encouragement, support, and courage.

One of Daniel Berrigan’s most prophetic challenges was addressed to those of us who believe we are called to be Christian peacemakers. It’s a quote from his book No Bars to Manhood about the cost of peacemaking vs. the cost of war-making—and the observation that war-makers are usually willing to pay a higher price for war than we peacemakers are willing to pay for peace. His prophetic words remain with us:

“We cry peace and cry peace, and there is no peace. There is no peace because there are no peacemakers. There are no makers of peace because the making of peace is at least as costly as the making of war—at least as exigent, at least as disruptive, at least as liable to bring disgrace and prison and death in its wake.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!