Activism

Juliana was in high school when she first joined Our Children’s Trust to sue the Governor of Oregon for a stable climate. During my environmental education classes, I’ve discussed the litigation to illustrate the importance of a long-term view even for an urgent planetary crisis. When my undergraduates prepare conservation workshops for local schools, they know that Juliana once sat in their places. She hopes to advocate for them in the U.S. District Courthouse in Eugene, Ore. in what may be the lawsuit of their lifetimes. And regardless of this Supreme Court’s decision, youth will gather on the courthouse steps to call for their right to a stable climate.

Despite the lack of coverage her faith has gotten, the influence of Christianity on her advocacy has remained constant. It is often difficult for people to associate Christianity with activism because it has become so weaponized, she says. “Christianity has been co-opted by people who have a political agenda, and have a very particular narrative that is steeped in racism, and classism, and sexism, and all of these other forms of oppression,” she tells me, “I’m the kind of Christian that recognizes who Jesus was — and Jesus was the first activist that I knew, and the first organizer that I knew, and the first example of how to be in service to people.”

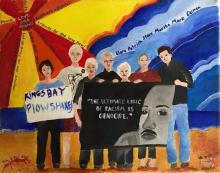

A group of about 20 peacemakers are embarking on an 11-day, 110-mile walk from Savannah, Ga., to Kings Bay, Ga. Named, “Disarm Trident: Savannah to Kings Bay Peace Walk,” the action is a call to abolish nuclear weapons globally and is supporting the seven Catholic activists arrested back in April on the Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base back in April.

“We will walk in nonviolence and prayer with the hope of bending the moral arc of the world towards justice and peace,” Kathy Kelly, one of the organizers of the walk, said in a news release.

“They shall not die in vain,” then, is very different from the concept embedded in “our thoughts and prayers are with them.” The former resounds as a call to action, while the latter connotes resigned quietism. Acquiescence, of course, is not the message that Bush, King, or Wilson intended when they used the phrase. They meant to inspire their listeners to make a change, to reinvigorate their commitment to a cause. They were exhorting people to ensure that the lives of the victims would not be lost in vain. In this version, redemption has not yet occurred. It requires further action on our part.

2. The Online Gig Economy’s ‘Race to the Bottom’

“ … while freelance websites may have raised wages and broadened the number of potential employers for some people, they’ve forced every new worker who signs up into entering a global marketplace with endless competition, low wages, and little stability.”

3. How Some Women of Color Were Left Out of the Minimum Wage Hike

“I see my job as the work of God, but God is angry because he sees that my job is making me sick needlessly and is mistreating me. We have been treated like slaves.”

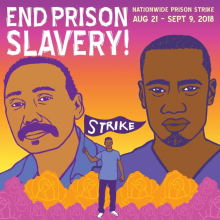

From Florida to California, imprisoned activists are organizing work stoppages, boycotting prison commissaries, and going on hunger strikes to draw attention to injustice in the U.S. prison system. Faith groups such as Christians for Socialism and The Friendly Fire Collective are supporting these prisoners as they hold a 19-day strike protesting what they call “prison slavery.” They see fighting for justice alongside prisoners as an important expression of their faith.

And then jazz enters the scene, a music that grapples with chaos and comes out with soul. In the tension of clashing notes and melodies, fingers flying across valves and keys, the band finds a groove that communicates the experience of the civil rights movement

Ramirez: I think like what you said, it's taking the side of the broken, the beaten, and the defeated. It’s knowing that when you say, “You just gotta lift yourself up by the bootstraps,” that not everybody has boots to be lifted up by. Justice looks like that. It looks like taking the side of the one being accused, the one being pummeled, not even just today, but throughout history because there are whole people groups who have been pummeled. Justice looks like giving people a taste of a true Jesus. Jesus would go to the woman at the well even if all of culture said not to, even if people looked down on him, even if it might have been bad for his reputation, that’s what he did. So often we like to tell good stories and take pictures of refugees and orphans somewhere else, but we very much like to ignore the causes that we should be fighting for here. For me, that's what justice looks like.

THREE RECENT FILMS portray heroism as ordinary people behaving with conviction under extraordinary circumstances. In Sully, an airline pilot lands safely in the Hudson River; in Snowden, a man speaks truth to power when he realizes it has been lying to him; and in the three-minute short We’re the Superhumans, British Paralympians and others with disabilities dance, jump, run, and fly to a big-band soundtrack. They are changing the world by challenging dominant cultural images of “able bodies,” “normal,” and “strong.”

Musician and activist David LaMotte has a theory about effective activism: An individual hero single-handedly overturning monstrous injustice isn’t a harmless cliché trotted out in TV or film dramatizations. Projecting near-supernatural power on such people is not only inaccurate, it denies them an even greater power: to truly influence others. If Rosa Parks or Martin Luther King Jr. were merely magicians, how can any of us respond other than applaud their tricks and despair of our capacity to challenge the oppression we discern in our own times? In World-Changing 101 (a book whose title is both serious and ironic), LaMotte suggests that this harmful fantasy ignores the strategic preparation and community support that nurture effective activism. Montgomery bus boycott handbills were printed by a group led by a teacher, Jo Ann Robinson; she had worked for years as a civil rights activist, including preparing for such a boycott. Printing handbills, sharing cars, telling hopeful stories, serving lemonade to tired marchers—all were vital parts of the body of change. Rosa Parks sat down alone, but she got up with many.

The cinematic heroes who don’t look like real-life activists avoid community, tending to act alone (Batman at least has a butler). Instead of painstaking planning (trial and error too), they spring into action or reaction when the bad guy is already halfway to victory (the villain often confidently explaining his dastardly plan just before it is foiled). They’re typically not around for the work of integrating the aftermath.

But Sully sees heroism as doing what you are trained to do—repudiating the notion that an emergency landing is a “miracle” rather than an act of human skill. Snowden tells how a whistleblower enlisted distinguished journalists so his revelations could be ethically told. And in the most glorious image of the year, We’re the Superhumans parallels one man in a flying wheelchair with another cleaning his teeth. Just getting out of bed can be heroic

Organized by Avaaz, a U.S.-based civic organization that emphasizes global activism, intends for the "Monument for our Kids" to put pressure on Congress to take action on gun control. Images of the striking visual have been widely shared on social media, with the hashtag #NotOneMore.

But it would not be lost on him, the silence — our silence — on the very principles Christianity was founded on: love of neighbor, care for the poor, welcoming all. Blaise had only to renounce these values to stop the horrors inflicted upon him. Just a word to save his own neck. But he refused. Even as he was tortured and executed. How tame our religion would seem to him now, how close to the trappings of the Empire whose politicians had hauled him off to jail.

And this is the America I believe in. No matter how we differ in our beliefs or practices, this country is meant to be a place where all of us feel safe and have the opportunity to thrive. So — despite demeaning rhetoric, stigmatizing policies, and acts of hatred and violence — I have hope, because I choose to see the many ways that people of faith and goodwill are pushing back. I hope that you do, too.

The Women’s March in 2017 was one of the largest protests in history. Why is it that coworkers and friends who are active in social justice movements did not even realize that the march was taking place again this weekend? Why is it that I am still explaining why it was important for me to attend?

MY MEDIUM OF choice is usually words. My activism often takes the shape of a column, sermon, or talk, a march or protest, lobbying representatives, attending meetings “to be a voice,” and voting. But recently, I took on activism with a needle and went back to a hobby of mine to bring my words to life: cross-stitching.

Through the miracle of social media, I was connected to Alicia Watkins—who offers back-stitched pithy sayings, and images of microbes, through her Etsy shop, including a pattern to stitch “Nevertheless, she persisted” on a tiny piece of fabric. Tiny stitches formed the letters and communicated what many women across the globe do, through a type of art form that is often disparaged as “women’s work.” Watkins and I are not alone. Shannon Downey of Chicago calls the activity “craftivism,” and through it she raised more than $5,000 in November 2016 to combat gun violence.

The irony is not lost on me. It’s actually what I love about needlework. Textile art, embroidery, sewing, darning—across time and space they have been women’s work, girls’ work, the work of the poor. Nowadays we can sell the work online and get paid through PayPal, never actually connecting in real life, not even through a middle-person. But I was taught to sew because clothes and socks were not as disposable as they are now, 40 years later.

“I really feel like activism is a form of sharing that love that God has given you,” she said. “Realizing that this world is made for all of us is something that’s transcending, and we have to inspire each other.”

Victims of trafficking get 45 days of what the government calls “recovery and reflection,” and care is offered via the Salvation Army. But traumatized, destitute people need far more than help for just six weeks, Archer discovered. This is where her parish came in.

“These dark times call for a different kind of scholar. We must step into the fray,” Glaude said. He concluded, “If you choose to sit on the sideline, you have chosen a side."

"We must talk about poverty, because people insulated by their own comfort lose sight of it."

If you went to church after Charlottesville, DACA, or the latest racial violence in your community, and were disappointed your pastor didn't speak, then it's time for you to act. Sitting and not liking what’s going on matters as much now as it did to stay in a segregated church back then. It’s time for you to find others in the congregation who are also disappointed. It’s time for you to go to your pastor and other leaders in the church. It’s time to insist he/she begin to speak justice — gospel — from the pulpit. (Pastors, it’s time for you to find those in your congregation who will stand with you as you do the same.)

It is easy to slip from defending the weak to attacking those Paul describes as the "weak person,” those who are attached to rituals and rules that are unnecessary but benign. If I allow myself to be drawn into self-righteousness, I find myself casting judgment for every little disagreement. I want to stop thinking of my opponents as my siblings in Christ. I want to do exactly what Paul cautions against when he says, "let us not pass judgment on one another any longer, but rather decide never to put a stumbling block or hindrance in the way of a brother" (Romans 14:13.)