This interview is part of The Reconstruct, a weekly newsletter from Sojourners. In a world where so much needs to change, Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair. This week features a guest interview by Sojourners online editorial fellow Ezra Craker. Subscribe here.

Growing up, my dad would take me and my siblings out for “presidential pancakes” each election. We’d tag along to the polls and then get treated to a big breakfast before school at a local diner. (In lieu of a sit-down meal, we’ve also done “midterm McDonalds.”)

My dad’s purpose was to instill the virtue of doing one’s civic duty. As I look to November, I see that the tradition can serve another purpose too: drowning election-season dread in copious amounts of butter and maple syrup.

It goes without saying that we’ve got plenty of dread to spare this year. Since President Joe Biden won the presidency in 2020, former President Donald Trump and his allies have falsely claimed that the election was rigged. Millions of Americans agree. Meanwhile, many other Americans fear how far Trump could take his authoritarian impulses in a second term. As our political culture becomes more tightly wound, the nuts and bolts of our democracy seem to be coming loose.

For the average citizen, it can be hard to verify every claim we see circulated in partisan media or online. Despite election law being clear that a party can choose its nominee at convention, for example, many Republicans claimed it was “too late” for Biden to step down from his reelection campaign.

That’s why I wanted to interview Chris Crawford, a policy strategist on free and fair elections at Protect Democracy, a nonprofit dedicated to defeating authoritarianism and strengthening democratic institutions. A Catholic, Crawford helped create the Faith in Elections Playbook, a resource for faith communities who want to support the 2024 electoral process.

Crawford and I spoke last month about the logistics of elections, conspiracy theories, and the role of faith communities in defeating authoritarianism.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ezra Craker, Sojourners: How do we know that American elections are secure in a logistical and technical sense?

Chris Crawford: One thing to understand as we get into the nuts and bolts of elections is that there’s a lot of false information out there, but also people are living their daily lives. They have a lot on their plates. So, people can be confused in good faith or not be paying attention to these kinds of things.

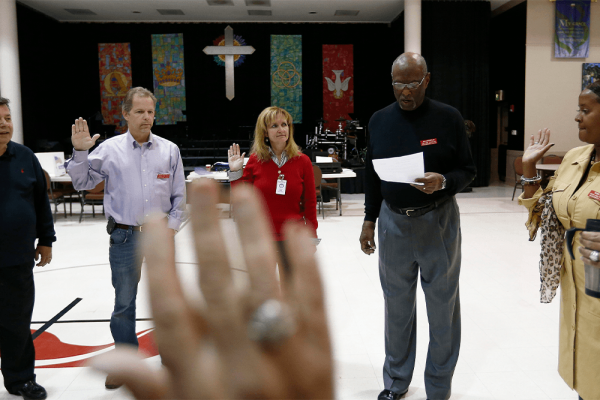

Thinking about our election system, one of the most important things to realize is that the elections are run by everyday people across the country. They are not run from one election hub in Washington, D. C. We have thousands of counties running elections. We have different rules for every state. We have about a million poll workers who are everyday people, who are well trained on the process, who step up and serve their communities.

And there’s also a lot more transparency than I think people recognize. There are opportunities for them to get involved, for them to go watch the way things are going and to verify that the system is working correctly.

And so that’s something that we’re focused on with some of our work at Protect Democracy and with Interfaith America is helping people see themselves reflected in the process as a means of building trust in our elections.

What are some of those specific norms and procedures — ones that might not seem relevant to the average voter — that will be important to observe and safeguard in November?

For one thing, any sort of election equipment that is going to be used by an election system. Every state has a rigorous bidding process for selecting what type of equipment they might use. And then that all has to be tested and retested. Many of the tests are run in public so that everyday people can go watch the process, have it explained to them, and they can see the way that the process actually works, that the equipment actually works. And then they’re stored securely until election day.

The poll workers and election officials at all the different polling locations have very strict guidelines on how to handle all of the equipment, how to handle all of the ballots, for example. You can see these people, in real time, handling these things effectively and following the rules.

We need a million poll workers. The best way for people to increase their trust in the process is to actually sign up and be someone working on the front lines of our elections, helping to check people in when they go to vote, helping to count the ballots, things like that.

I’d love to see more people who have questions about our elections get those questions answered by being part of the process.

Despite these great procedures and checks that make it possible for people to understand how elections work, there is a low level of trust around elections. A May 2023 poll from Monmouth University found that almost one in three Americans believe that Biden only won the 2020 election due to voter fraud. There is, of course, no proof for that, but how would you be able to tell if an election were actually rigged? When would you become worried as an expert on elections?

I’m going to pivot a little bit to describe some of the ways that we know that the 2020 election was legitimate, and also to push back on some of what you hear about the 2020 election and the 2024 election.

You have the testing of election equipment on the front end. You have checks and balances built in that poll workers generally have to be from both parties. There are official challengers in some states appointed by the state political parties watching the process. There are election observers from both parties. And again, each state has different rules on how to do that. The voting and tabulation machines are publicly tested. In many cases, people can go show up and just watch that.

After the election, states have different ways of auditing their results. Something we saw after the 2020 election was people claiming that we needed extra audits that went beyond any of the sort of reasonable guidelines that any of the states have. There might have been an impression that opposition to audits that didn’t follow best practices was actually opposition to auditing generally, but nothing could be further from the truth.

Every state has their own post-election audit system where they check to make sure that the results are accurate. There was a conversation on Twitter recently with Elon Musk, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and some others about paper ballots. And former president [Trump] talks a lot about [how] we need paper ballots. It turns out they’re right in a sense. Paper ballots are good, but the good news for them is that about 95 percent of voters, according to an organization called Verified Voting, will cast their ballot in a jurisdiction that has some sort of paper marking in the 2024 election.

Even if you’re making selections on a machine, for example, results are printed, submitted, counted, and stored. What that means is that you can recount those votes easily. You can check them; you can audit them. And that’s what we saw in a number of states in 2020, including recounting the entire race in Georgia.

So, to your question of, “How would you tell if an election was illegitimate?” You would have to look at all of these different processes that are built into our election system and see them break down or see them overruled. And that’s something that we just have not seen. And I don’t think anyone anticipates seeing it.

I want to go back to what you said about the pushback against the auditing process [and] people wanting more auditing instead of just the standard procedure. Trump’s platform and policies are rightly regarded as a threat to democratic institutions, but the perception of many Trump supporters is that the 2020 election wasn’t democratic, that the will of the people wasn’t honored. We can call it politically motivated, but the value that is being appealed to there is democracy. As someone working on building a broad coalition against authoritarianism, what would you say to someone with that line of thinking?

I think of this both as a democracy advocate and as a Christian. I put a big value on honesty and on the truth. A democracy needs well-informed people who understand what the truth is, and we need leaders who make decisions based on the truth.

I see this especially for Christians involved in politics: We, as an absolute priority, have to be committed to the truth and to being honest. In the 2020 election we saw a lot of people abandoning a commitment to the truth for political gain.

I found that especially disheartening because I think Christian leaders in our politics should be committed to the truth. And if the people they are leading believe a lie, they have an obligation to correct it, not to accommodate it. So, that’s something that continues to bother me the most in this environment.

You mentioned your faith. I know you’re a Catholic. Can you say more about how your faith has led you to this democracy work and how it sustains you?

All of my politics is generally rooted in a position of valuing human dignity and striving for human flourishing. I care about democracy because I think that democracies have proven to be the form of government that best protects human rights and human dignity. I also think that every freedom that we care about — including our religious freedom — rests on a foundation of democratic ideals [and] pluralism and that in turn rests on free and fair elections and other pieces of democratic institutions.

That’s part of why this matters so much to me also as a Catholic. In Catholic social teaching, we value participation and having people participate in building their own future. Building the future of their neighbors is really valuable as well. So that’s at the root of where my Catholic faith informs my democracy work.

You’ve written and spoken about the critical role that faith communities play in protecting democracy. What are the most effective ways that faith groups can help safeguard the democratic process leading up to the election this year?

[During the 2020 election], I was helping to organize faith leaders responding to the multiple challenges facing our democracy, including trying to run an election during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were a lot of religious leaders who were interested in getting involved but worried about seeming partisan. Or they were worried about whether or not they could follow every technicality of the rules. I found myself wishing I had more time and more resources to help them navigate the election environment.

[Protect Democracy and Interfaith America] basically launched a website to help those religious leaders and institutions find nonpartisan ways that they can get involved in our elections. This is called the Faith in Elections Playbook.

[Faith leaders and institutions] can find ways to get involved that are in line with their values, their skill sets, and the needs of their specific communities. As we put this together, we — for the most part — did not come up with new ideas. There are a lot of faith-based organizations and a lot of secular organizations that partner with faith-based organizations who are already doing this work and doing it well.

There are several ways that we are inviting people to get involved. A few of them are recruiting poll workers or signing up to serve as poll workers. Others are providing a peaceful presence at polling locations. For example, serving as a poll chaplain, doing de-escalation training, or providing food and water at polling locations where there are long lines.

I think it would be great to see faith leaders meeting with their election officials, bringing the questions that their members might have and reporting the answers back and building a relationship of trust. This will look different for different organizations in different places. You might have a Christian pastor who has an entire congregation that’s concerned about the integrity of our elections, and they might have a meeting where they just get all these questions answered.

You might have interfaith coalitions that want to meet together and maybe do a public event, something like that.

There’s such a need for poll workers. Specifically as a Christian, being a poll worker [is] a positive contribution [because] it intersects with Christian values like hospitality. There’s a role that poll workers can play in recognizing the image of God in every voter that’s coming forward, the human dignity of that person, and to treat them as valuable.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!