MY FIRST EXPOSURE to writer Lamorna Ash was the thumbnail image for an interview on YouTube, giant text emblazoning her face with the words “The Case for Christianity.” I must admit, I was skeptical. Granted, I am a Christian who has certainly “made the case” for the profound reality of Jesus of Nazareth now and again—but recently, apologetic arguments and “hardened atheist turned Christian” testimonials have left a sour taste in my mouth.

Perhaps it’s the way that media in that sphere tends to be loaded with culture warrior “Christian Apologist DESTROYS Atheist Snowflake” language. Maybe it’s that, frequently, the case for Christianity actually tends to be the case for Western dominance, whiteness, and heteronormativity. Or maybe it’s even simpler than that: Often, the sheer dogmatic certainty with which these “convert influencers” tend to speak just doesn’t feel honest. Either way, as a queer believer, the genre usually feels out of step with my daily walk.

Nevertheless, I decided to give this particular interview a listen—and Lamorna Ash was nothing like what I’d anticipated. A young and openly queer British woman with a lyrical voice and a heart for Palestine and trans people? This was not the person I’d traditionally expected to make the “case for Christianity.”

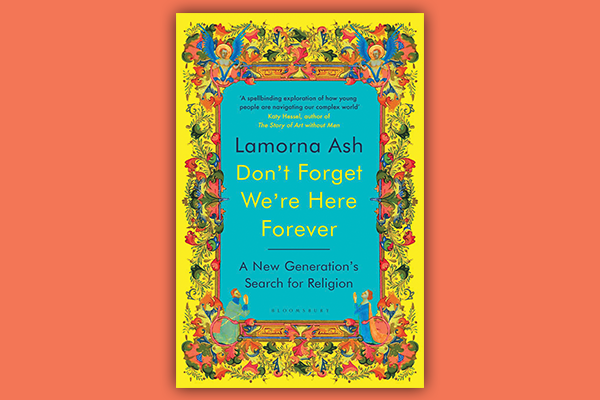

Ash’s latest book, Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion, is a similar Trojan horse—and I fell in love with each empathetic and introspective chapter. Don’t Forget is a self-portrait of a poet and journalist seeking to understand the religious conversions of others while exploring the transformations she increasingly feels within herself. After two of her friends convert to Christianity, Ash decides to see whether this strange religion she’s only ever known through cultural osmosis might have any real substance or implication for her life.

To find that substance, Ash immerses herself in a wide swath of religious communities across the U.K. where she learns what Christianity means to a variety of young (and often recently converted) believers in different denominations. As a relative newbie, she brings wide-eyed curiosity to every community she visits—and her humble sensitivity toward the stories of others, despite their perplexing differences and dogmas, is her greatest strength.

Much discourse has been spun about Gen Z’s return to religion, often in tandem with suggestions of a broader cultural pivot away from progressive values. Bible sales in the U.S. are booming, up 22% in 2024 per Circana BookScan. Christian apologists are appearing on Joe Rogan. For the first time in modern history, young men are attending church as much as—or more than—young women, overturning the long-standing pattern of female predominance in religious life. And that’s not to mention the political realm, where executive orders are attempting to enforce “biblical” models of gender and sexuality, among other Christian nationalist goals.

I’ve witnessed firsthand the spiritual curiosity palpable in Gen Z.

I sympathize with and even celebrate some qualities of this moment, despite its overtly repressive downsides. As a filmmaker whose work often explores the transcendent, I’ve witnessed firsthand the spiritual curiosity palpable in Gen Z. We are an increasingly isolated generation—and our ongoing search for committed rhythms of community inevitably leads us back to the sheer cultural advantage of the church in human life. Many of the converts Ash interviews in her book, particularly the young men, convey as much.

Cultural advantage, however, is not enough to make a society deeply Christian. C.S. Lewis made this point in The Screwtape Letters, with demons as tempters intent on making people view Christianity merely as a means to an end:

[People] or nations who think they can revive the Faith in order to make a good society might just as well think they can use the stairs of Heaven as a short cut to the nearest chemist’s shop. ... Only today I have found a passage in a Christian writer where he recommends his own version of Christianity on the ground that “only such a faith can outlast the death of old cultures and the birth of new civilisations.” You see the little rift? “Believe this, not because it is true, but for some other reason.” That’s the game.

Many of the prominent proponents of this supposed Christian revolution—such as Elon Musk, Jordan Peterson, Andrew Tate, and (comically) Richard Dawkins—are very transparently not even Christians themselves. Regardless, they see “Western Christian values” as a helpful construct to fortify the hierarchies—such as capitalism and patriarchy—that have brought them success. These men may speak with dogmatic certainty about religion, but few of them seem interested in the real Jesus of Nazareth or the Sermon on the Mount. Musk and Dawkins specifically have described themselves as “cultural Christians,” with Dawkins even saying, “I like to live in a culturally Christian country, although I do not believe a single word of the Christian faith.” To put it another way: These “cultural converts” seem to want the fruit but not the tree.

Coley review mid.png

Even Ash is not immune to a somewhat instrumental view of Christianity. As she begins to warm toward a life lived through the lens of faith, she is upfront about the fact that much of her rationale is related to the ways that religious practices—such as prayer, intentional community, and a belief in the possibility of a better world—strike her as personally advantageous. At one point, she writes, “I think I might need the ritual of Sunday worship to discover the courage to become the version of myself I would like to be.”

For Ash, though, the “advantage” of faith lies not in the hierarchies it upholds, nor in any certainties it provides—but in its ability to give people new eyes to see themselves and their neighbors as made in the image of God. The fact that Christianity seems to help leads Ash into a stronger feeling that there must be something true buried within. She trusts, however tentatively, that this fresh fruit must point toward a tree somewhere nearby.

Throughout Don’t Forget, Ash interviews many converts who are radically “sold out for God.” Often, it seems the more unquestioning these new believers are, the more alienated from them she feels—and aware of potential harms. Despite this, Ash’s ability to hold the unique experience of each frustrating individual she encounters with grace is powerful. In the end, it’s the converts who feel most questioning of their presuppositions, and yet carry on anyway, who convince Ash that it might be possible to embrace Christianity herself.

Anne Lamott said that “the opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty,” and Ash likewise makes repeated use of Jacob’s wrestle with the angel as a metaphor for what real religion looks like.

Nearing her conclusion, she writes, “My belief is not founded on certainty, and I don’t want to persuade anyone else of it ... [but] I’ll try to sing in tune with my cracked voice.” Ash’s trepidatious singing is a picture of an ideal that Gen Z often seeks: to remain conscious of potential pitfalls and still attempt sincerely to believe in something anyway. In a conversation often dominated by brash and dogmatic pundits, I found this “cracked voice” to be uniquely beautiful, curious, and faithful in all its honest wrestling.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!