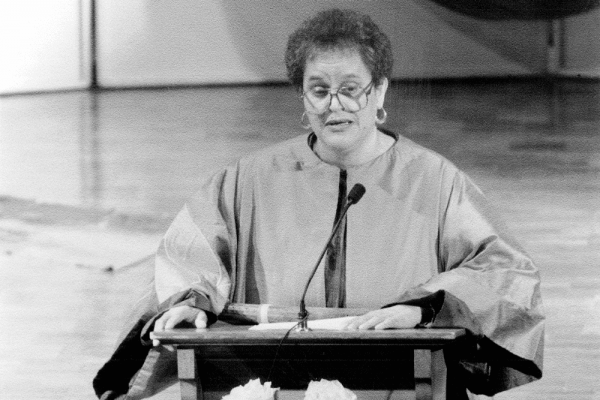

Delores S. Williams, a trailblazer and founder of womanist theology, died on Nov. 17 at 88. She was the author of Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk and a professor of theology.

Williams earned a doctorate from Union Theological Seminary in 1991, where she later became the first Black woman to hold a named chair at the school as the Tillich professor of theology and culture. She had four children and was married to Robert C. Williams, who died in 1987. Over her life, she wrote several essays, articles, and book chapters that helped establish womanist theology, which she defined in Sisters in the Wilderness as theology that takes the “faith, thought, and struggle of Black women seriously as a ‘primary theological source.’”

“[Williams] showed me and so many others that our questions and our insights are valuable, and can only enhance the ways in which we understand both the Bible and our faith lives working in the world,” Emilie M. Townes, dean and professor of womanist ethics at the Vanderbilt Divinity School told Sojourners by email. “She gave me the courage to dare.”

Serene Jones, president at Union, told Sojourners in a statement that she was “deeply saddened” at Williams’ passing.

“Her passing is a great loss to the world, to theological education, to womanist theology, and to our Union community,” Jones wrote. “Although she is no longer with us, her incredible legacy lives on through the many lives she impacted including myself, her many students here at Union and the many who continue to read her groundbreaking womanist work.”

Life and work

Williams was born in 1937 and grew up in African American communities in the rural South where, as she wrote in Sisters in the Wilderness, she saw the “forces bent on conquering black women’s power to resist and rise above obstacles.”

“But in spite of antagonisms, ordinary spiritual black women continued their struggle to resist and rise above the forces seeking to destroy their lives and spirits,” Williams wrote in the preface. “More often than not, they accounted for their perseverance on the basis of their faith in God who helped them ‘make a way out of no way.’”

She used the term “womanist,” originally conceptualized by author Alice Walker to describe Black feminists. She wrote about that Walker’s use of womanist provided “significant clues for the work of womanist theologians,” in a 1987 article in Christianity and Crisis.

In Sisters in the Wilderness, published in 1993, Williams writes: “While [womanist theology’s] aim is discourse and work with black women in the churches, it also brings black women’s experience into the discourse of all Christian theology, from which it has previously been excluded,” she wrote.

Womanist theology, Williams wrote, joined Black male liberation theology in its call for the freedom of all human beings and joined white feminist theology in its assertion of women’s dignity. Womanism critiqued white racist oppression, but it also identified and critiqued Black male oppression of Black females, and white feminist theology’s “participation in the perpetuation of white supremacy,” Williams wrote.

In the book, Williams builds her theology around the biblical character of Hagar, “a female slave of African descent who was forced to be a surrogate mother.” She saw Hagar’s story as congruent with the predicaments that Black women face in the U.S. and wrote of the African American tradition of appropriating Hagar’s story, reading it from the position of Hagar rather than her enslavers.

Williams did not see redemptive or salvific value in Jesus Christ’s death, telling the New York Times in 1998 that “The ministry of Jesus is what brought salvation to humankind … The cross represents only the results of that.”

Williams wrote for Sojourners in the 1990s on the topics of integration, democracy, and eugenics, writing particularly with an eye toward Black women. In a response to a Sojourners article on building a new economic system, Williams questioned whether the economics of a “living democracy” could be built in the U.S. without addressing racism in the “American consciousness.”

“A ‘living democracy’ cannot be built here as long as the national consciousness is infected with this cancerous ‘anti-blackism’ that is the heart of white racism,” Williams wrote.

Theologians, activists, and authors mourned and celebrated Williams’ life and work.

“Delores Williams was a pioneer of womanist thought who shifted the paradigm of how we think about the cross,” Kelly Brown Douglas, a theologian and dean at Union told Sojourners in a statement. “I remember her as a supportive friend and mentor to me and so many others ... I will miss her spirit, and I pray that we cherish and carry forward her pioneering legacy with the courageousness she demonstrated throughout her life.”

Candice Marie Benbow, author of Red Lip Theology, wrote that no book had shaped her thinking more than Sisters in the Wilderness.

“Womanist theology exists, in part, because of Delores S. Williams. We are better because she lived and dared to think critically about Black women’s relationship with God, the world and ourselves,” she wrote. “May her memory be a blessing and may we honor it through our work.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated on Jan. 3 to correct the date of Williams’ death to Nov. 17.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!