#blacklivesmatter

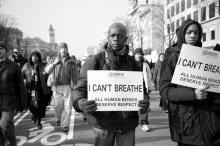

Over the past year, #blacklivesmatter has taught me that the work of theology is not limited to the hallowed halls of academic institutions or sermonic reflections from prestigious pulpits on Sunday mornings. At community meetings and rallies, I learned new hymns in the form of movement chants. I learned that protest can be a form of prayer. #Blacklivesmatter is more than a hashtag. It is a call for repentance. It is an invitation into a state of prophetic grief and collective lament that does not anesthetize us from our pain but allows us to reconnect to the depths of our humanity by feeling, together, the torment our silence on issues of racial injustice has sown. It is only together that we will be able to actualize the transformation God is calling us to effect in this world.

In honor of the one-year anniversary of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Mo., Sojourners asked a variety of faith leaders — Catholics, Baptists, Muslims, agnostics, evangelicals, and humanists — to reflect: How has your faith been challenged, affirmed, or deepened by the Black Lives Matter movement? Has your theology changed? And, most importantly, what are we being called to do?

Here’s what they said.

Even as the disciples of Jesus grieved at the foot of the cross, they understood there was work to be done. The work of justice is deeply political and requires an engagement in this present world. With tears in our eyes, we are called to march, rally, petition, sing, dance, create art, and use whatever gifts and talents we possess for the work of justice. The work of justice is deeply theological. Our church communities must foster a faith that gives people room to grow, to stretch, and to ask the tough questions. A grieving people need a theology for such a time as this, a theology that speaks to this present age. White churches, in particular, must end their silence and address the pain of grieving black lives, because the work of justice is collective. Even if you cannot possible understand all the reasons for our pain, you can come alongside a grieving people in love, humility, and solidarity.

1. Death of a Young Black Journalist

“The most basic instinct of a local reporter is to take the importance of her neighbors as a given. In a community like Anacostia—where more than ninety per cent of residents are African-American, one in two kids lives below the poverty line, and incarceration and unemployment rates are among the nation’s highest—this is another way of saying that black lives matter.”

2. Dear NBC, BBC, CNN, and Others: Mugshots Are for Criminals, Not for Their Victims

“Using a mugshot that has no relevance to the circumstances in which Sam DuBose was killed—up against a fully-uniformed photo of his accused killer—suggests that DuBose did something criminal to instigate the cop in his shooting. As yesterday’s grand jury decision confirms, this is blatantly not true. It warps the real story: a cop who allegedly killed an innocent man for no good reason.”

3. We Need to Talk About Feminism and Vocal Fry

“The clash here is not between anti-feminists and feminists. At its heart, the conflict over vocal fry is a clashing of feminist ideologies. … Wolf suggests that young women’s voices aren’t authoritative enough, and implies that they’re somehow squandering all the hard feminist work that came before them. But what’s really happening is a generational shift, both in feminism and in the workplace.”

Four Confederate flags were placed outside of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s church here July 30. Authorities said they are looking for two white men who were caught on surveillance video.

Authorities have images of the men placing the flags outside Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, said Atlanta Police Chief George Turner.

Local authorities are working with federal authorities and have not determined what charges might be levied, he said. They have not ruled out a hate crime, Turner said. An officer from the Atlanta FBI’s joint terrorism task force was on the scene “to better determine if any specific threats were received” and to provide support to Atlanta police, FBI Special Agent Steve Emmett said in an email.

The officer indicted for the murder of Samuel DuBose just blocks from the University of Cincinnati campus pleaded not guilty, NBC News reports. Outrage over the shooting death of DuBose, father of 10, during a traffic stop on July 19 has been widespread since video footage surfaced Wednesday, with calls for a murder conviction for officer Ray Tensing.

My people — that is, white evangelical Protestants — aren’t good at talking about race.

This fact has been born out by years of social scientific research. A number of years ago, based on thousands of interviews with evangelicals around the country, Christian Smith and Michael Emerson posited that, "evangelicals have a theological world view that makes it difficult for them to perceive systemic injustices in society."

Unfortunately, the situation hasn’t improved much in recent years. In 2014, the Public Religion Research Institute found that two-thirds of white evangelicals agree that black and white Americans receive equal treatment under the law. More than 80 percent of black Protestants disagreed with the same statement.

Apparently, white evangelicals just don’t think race is that big of a problem. And even if we did, we don’t have the conceptual tools necessary to address the underlying, structural forces at play. It’s time for us to start listening. But how? Where do we begin?

With Ta-Nehisi Coates.

PEOPLE HAVE CALLED me a lot of things: Host pastor of the #BlackLivesMatter freedom ride; student of teenage and Millennial activists; leader of a state commission advocating policy change; bail negotiator; street agitator; and militant mediator. Since the Holy Spirit was poured out onto the streets of Ferguson, Mo., and St. Louis in the wake of Michael Brown’s death, I’ve been called and challenged to play these roles—and more.

Yes, I did say the Holy Spirit. The same Spirit that fell at Pentecost as a dynamic demonstration of God’s power to overcome the barriers of language, ethnicity, gender, class, and sexual orientation. The Spirit of hope that caused a community once rebuked for its broken dialect to speak with one voice. The Spirit of holiness that enabled a people dismissed for “drunkenness” (see Acts 2:15) to form the first fruits of the church.

We may have missed it because those the Spirit fell on nearly a year ago weren’t wearing robes and stoles, but hoodies and bandanas. They weren’t singing anthems and hymns, but chanting what some would call obscenities. They weren’t called saints and disciples by the media, but thugs and outside agitators.

But last summer, in the week between Michael Brown’s death on Aug. 9 and Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon’s declaration of a state of emergency on Aug. 16, the Spirit was poured upon “all flesh” and our sons and daughters began to prophesy.

Week after week, we can take on the biggest issues we face as a society — from continuing racism, mass incarceration, inequality, and poverty to gender violence and human trafficking, climate change, ISIS — and just try to be hopeful.

Or we can start by going deeper, to a more foundational and spiritual understanding of hope — rooted in our identity as the children of God, made in the image of God, as the only thing that will see us through times like this.

I believe we should start there. Because the biggest problem we face — the biggest enemy at the heart of many of the issues we must address — is hopelessness.

And perhaps the most important thing the world needs from the faith community is today is hope.

How does a social movement begin? How does frustration meet courage and conviction to bring a people together to engage in transformative work? What seeds do we plant to change a nation?

Social movements do not form out of thin air. They arise out of people’s suffering. Social movements are rooted in moments when people decide to change the conversation. The growing momentum around this new conversation creates a movement — a swell of influence in society that has the potential to change minds and transform society.

As Christians we should recognize the language of black lives matter. After all, Jesus did not say "blessed is everyone," but "blessed are the poor" (Luke 6:20). He did not say "as you do it unto everyone, you do it unto me," but "as you do it unto the least" (Matthew 25:40). Jesus did not say "love everyone," but "love your enemies" (Matthew 5:44).

Continually Jesus drew our attention not to loving people "in general" but to specifically caring for those we would tend to discount or condemn. Black lives matter is exactly the kind of thing Jesus would say.

Socioeconomic reconciliation is the removal of gaps in opportunity, achievement, health, thriving, and well-being that exist between groups of people in our nation and world. In the face of myriad breaches of the common human bond and experience, a breakthrough act of the Spirit today would activate and agitate the established church in her ministry: a ministry of socioeconomic reconciliation.

The ministry of socioeconomic reconciliation will require a church empowered with tongues of fire and the gift of interpretation. These tongues must speak with a prophetic voice. But we must also have the heart and capacity to translate the words of marginalized communities into the language of policy, power, and program. That is why I thank God for the compelling, confusing roles I’ve been called into over the last nine months. This form of reconciliation requires the church to fulfill of the vocation of the militant mediator, which offers as much renewal in the streets and city hall as we experience in the sanctuary.

Douglas writes in response to the murder of Trayvon Martin, tracing the intellectual and cultural genealogy of a “stand your ground” culture — one that polices our public ‘white’ spaces, and kills men and women of color who are in them. Sadly, as the deaths of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray show, our cops and our culture are still killing innocent people of color. We aren’t a post-racial culture at all.

Stand Your Ground takes a cruciform shape: we face the death of the cross in her depiction of the despair of a culture that kills its citizens, before rising in the resurrection hope of a black faith.

Recent protests in Baltimore are raising the question of (non)violence anew. Should violent protesters be criticized? Should Christians call for nonviolence?

Some bluster “Of course!” while others say that’s not the point.

Over at The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates, who grew up in Baltimore, is challenging calls for nonviolence in an article entitled “Nonviolence as Compliance.” Calling “well-intended pleas” for nonviolence “the right answer to the wrong question,” Coates writes:

When nonviolence is preached as an attempt to evade the repercussions of political brutality, it betrays itself. When nonviolence begins halfway through the war with the aggressor calling time out, it exposes itself as a ruse. When nonviolence is preached by the representatives of the state, while the state doles out heaps of violence to its citizens, it reveals itself to be a con. And none of this can mean that rioting or violence is "correct" or "wise," any more than a forest fire can be "correct" or "wise."

The line bears repeating: “When nonviolence begins halfway through the war with the aggressor calling time out, it exposes itself as a ruse.” Are newly scared white folks simply “calling timeout?”

Coates wants to ground our conversation about violence in the narrative of a larger “war.” For him, violence did not “break out” last night – violence has always been present. Coates wants to shift our focus from the shorter story of rock-throwers to the much longer story of the black experience in the United States.

As the clergy marching in Baltimore put it, “There’s been a state of emergency way before tonight.”

As thousands took to the streets in Baltimore on Monday night to protest the death of Freddie Gray on th eday of his funeral, nearly 100 clergy joined the protesters.

Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black male, died April 19 while in police custody, one week after his arrest. Although one of the officers reported Gray “was arrested without force or incident,” Gray died of severe spinal injury, prompting citizens to question how Gray was treated in custody.

In “A Newsfeed of Fear” (Sojourners, May 2015), Gareth Higgins argues that our newsfeeds often scare us into believing the world is getting worse when the world is actually getting better.

Although I resonate with a call for calm in an age of violent clickbait, we cannot discuss “A Newsfeed of Fear” without talking about race in post-Ferguson America. When we say our newsfeeds are filled with fear, we need to think more about which newsfeeds are making us afraid and whose fear we’re discussing.

For example, when Higgins bemoans “horrifying, brutal videos, edited for maximum sinister impact,” perhaps a reference to the all-too-familiar videos of ISIS hostages, I actually envision Walter Scott and Eric Garner and Tamir Rice and all the others. While the videos produced by ISIS are fearmongering propaganda intended to provoke, we wouldn’t want to call newsfeeds unmasking the reality of police brutality a corrupting influence on our society, right?

And in this context Higgins’ claim that the world is actually getting better is especially dangerous. Advising police brutality whistle blowers to keep their violent videos to themselves because they paint “too cynical a portrait of the improved race-relations in our society” would border on the insane.

The problem with media is not so much that it makes us fearful, but that it makes certain people fear certainthings and certain other kinds of people. It makes my mom fear that her granddaughters will get kidnapped in a very safe neighborhood. It makes me, a white guy, fear walking past black men in hoodies at night, and not white guys in polos. What you fear depends on where you’re standing and what you’re watching.

From where Higgins is standing, “our culture has been hoodwinked by the idea that we’re living in the center of crisis, when actually we’re in the midst of the evolution of hope.” In his eyes, our culture cultivates a false sense of constant terror.

But we need to ask: whose culture? When I read #BlackLivesMatter activists, they seem to say: “no, most people have been hoodwinked by the idea that ‘our’ (meaning American) culture is living in the midst of the evolution of hope, when actually ‘a certain (black) culture’ is indeed in the center of crisis.” So who’s right about the value of violent, fearful newsfeeds?

It depends on where you’re standing and what you’re watching.

Last month I traveled to Selma, Ala., to commemorate the anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches. Fifty years ago, images of the “Bloody Sunday” brought the horrors of racial terrorism into the living rooms of the American public, as brutal images of marchers left bloodied and severely injured dominated the evening news. As a young African-American clergywoman and interfaith organizer, I am the fruit of the labor of civil rights pioneers in places like Selma, Ala., Greensboro, N.C., and Jackson, Miss. Today, the work continues through the organizing and activism of young people across the country catalyzing a 21st century interfaith movement for civil and human rights.

On April 14, I will join together with many of these young leaders in celebration of Better Together Day. An initiative of Interfaith Youth Core, Better Together Day amplifies the power of interfaith cooperation as a tool for positive social transformation.

This year participants are encouraged to have a conversation with someone with a different moral and ethical belief system than their own as a means of breaking down barriers and combatting bias. Research shows that when people get to know someone different from them, their sentiments toward that entire group shift for the positive. Put simply: Our biases decrease when our encounters with “the other” increase. The event could not come at a more timely moment. The headlines of major newspapers over the past 12 months, from the killing of three Muslim students in Chapel Hill, N.C., to the rise of the #blacklivesmatter movement, show that there is much work to do in confronting bigotry and systemic oppression in our nation.

I experienced the transformative power of interfaith encounter and exchange firsthand in the fall of 2009. Fresh out of college, I took a 6-month position as community organizing fellow at a small food justice organization in Nashville, Tenn. My assignment was to support a new campaign designed to engage religious communities as advocates in food deserts — communities with little to no access to affordable, healthy food. New to the South and to the working world, I arrived my first day with a stomach full of butterflies and anxiety. A woman with dark curly hair and slight Southern drawl greeted me at the door and my nerves immediately subsided. Her name was Miriam, and in a few short months, she would change the course of my life.

When The Bible miniseries premiered two years ago, controversy swirled around its depiction of a dark-skinned Satan who some said resembled President Obama, as well as its portrayal of white main characters in the Moroccan landscape.

Fast-forward to the premiere of the sequel, A.D. The Bible Continues, on Easter Sunday (April 5), and you’ll see a decidedly more multicultural cast, the result of “honest” conversations between black church leaders and the filmmakers, Hollywood power couple Mark Burnett and Roma Downey.

“For too long religious programming has neither reflected the look of biblical times or the diversity of the church today,” tweeted the Rev. Barbara Williams-Skinner, a Maryland-based black activist, writer and scholar.

“We made this point to Mark and Roma after #BibleSeries, and quite frankly they listened. I’m glad for that.”

Now, in a partnership with the 12-part NBC miniseries, an African-American Christian publishing house will host online resources to help viewers connect the holy book to Africa.

In the wake of tragic shootings of unarmed black men at the hands of vigilantes and white police officers, many institutions across American society, from the president on down, have sought to foster “national conversations” about race.

Perhaps surprisingly, an agency of the Southern Baptist Convention is sponsoring one of the most important and fruitful such conversations. The SBC’s public policy arm, the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, has hosted a summit on racial reconciliation last week in Nashville, Tenn.

Founded in 1845 in a split over slavery, the SBC has made laudable efforts to overcome its racist past. Some moderate and liberal Southern Baptist leaders prophetically denounced racism and supported the civil rights movement, but those very leaders were forced out of the denomination during a period of conservative resurgence in the 1980s. Today’s SBC leaders are in the tenuous position of saying that moderates were right about race but wrong about everything else.

Southern Baptist leaders are determined to challenge the lingering indifferent or crude attitudes on race where they still exist among the denomination’s mostly white, mostly Southern constituency.

Charged with carrying out the SBC’s political priorities, the ERLC is best known for its advocacy for religious freedom and against abortion and same-sex marriage. Yet in the wake of unrest over last year’s deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., and Eric Garner in Staten Island, N.Y., the ERLC hastened its plans to hold a summit on race.

The Nashville event drew more than 500 clergy, lay leaders, and seminarians from across Southern Baptist life. Thousands more watched a live stream online. The speaker lineup was male-dominated but was decidedly mixed race. The ERLC was much more eager to hear from ethnic minorities at this summit than it was to hear from gay people at its fall conference on homosexuality.

While the sexuality conference projected certainty and unanimity — acceptance of homosexual expression is inconsistent with Christianity and will not be tolerated in Southern Baptist churches — white Baptists came to their race summit with genuine humility and a spirit of repentance for the harm racism has caused.

Dean Inserra, lead pastor of City Church in Tallahassee, Fla., challenged the audience: “When you say a school or neighborhood has ‘gone downhill,’ what are you saying?”

Conceding his own need for greater empathy, Inserra recalled asking a black clergy colleague to help him understand how police violence affects black communities.

While statistics, tweets, marches, and articles can bolster and enliven movements, art brings in the endurance. Art makes injustice a song that gets stuck in your head. Art makes murals out of obituaries, and hope out of statistics. Below, check out some of the art surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement:

1. Epitaph as protest. In “All Eyes Are Upon Us” (Sojourners April 2015) Gene Grabiner references 14 fallen people of color—men, women, and children, from 1973 to 2014—all casualties of “this war against the people.”

2. Nightmares. In her spoken word poem “black. anathema.”Jessica Edwards mourns the feared death of her unborn black child: “My soul mourning you prematurely, / clutching my empty womb bitterly.”