Faith

Editor’s Note: We at Sojourners thought it would be nice to share first-hand reflections on our inaugural annual conference, The Summit: World Change Through Faith & Justice, from participants. Our first post comes from Sara Johnson, who hails from Ennis, Mont. and is the founder of the Million Girl Army, a brand new non-profit launching this year focused on engaging middle school girls in the U.S. on gender justice advocacy. Sara is an emerging leader who was able to attend The Summit because of a sponsorship from one of our Change Maker donors. The donor covered all of Sara’s costs, from registration to travel and had a tremendous impact on Sara’s work, as she shares below.

Although nervous to be a founder of a non-profit that hasn’t officially launched yet attending a conference with heavy hitters in the non-profit world, within seconds of walking into the initial Summit gathering I was glad I came.

If Christians stopped bickering about church, presenting sex as a first-order concern, telling other people how to lead their lives, and lending our name to minor-league politicians, what would we have to say?

We need to figure that out, because we are wearing out our welcome as tax-avoiding, sex-obsessed moral scolds and amateur politicians.

In fact, I think we are getting tired of ourselves. Who wants to devote life and loyalty to a religion that debates trifles and bullies the outsider?

So what would we say and do? No one thing, of course, because we are an extraordinarily diverse assembly of believers. But I think there are a few common words we would say.

“If, as Christians, we believe that peace is rooted in Christ, then how we build that peace within us, in one way, is through the disciplines of solitude and silence; through spending time with God. Solitude is not necessarily extremely easy process, because it will bring to the fore all sorts of things that are within us. We will get to know ourselves in a fuller way. In solitude, where you know that God is with you, you can just be with God, and there is no need for a mask. Also, your humility might grow because you will see yourself as you really are — in a way that needs to be healed and transformed.”

THROUGH THEIR EYES

In 2011, Raul Guerrero provided 100 Kodak disposable cameras and taught basic photography skills to nine young students in the Newlands area of Moshi, Tanzania. The Disposable Project book brings together their images of their community, with text by Guerrero. the-disposable-project.com

JOURNEYING

“Migration has been, for centuries, not only a source of controversy but a source of blessing,” Deirdre Cornell writes in Jesus Was a Migrant. Inspired by ministering among immigrants in different settings, this is a beautifully written set of deeply humanizing reflections on the immigrant experience and Christian spirituality. Orbis Books

LOVE. THAT'S WHAT moves mountains. That’s what the inimitable Dr. Maya Angelou shared with Oprah Winfrey in an interview a year before Angelou’s passing on May 28, 2014, at the age of 86.

In the days following her death, tributes blanketed the television and internet. Perhaps the greatest came on Sunday evening, June 1, as Oprah Winfrey aired a series of exclusive interviews with Dr. Angelou. Thus, the prophet spoke from the grave and this is what she said: “Love moves mountains.”

Jesus said faith moves mountains—faith the size of a mustard seed (Matthew 17:20). Did Dr. Maya Angelou dare to contradict Jesus? The poet/prophet says love. Jesus said faith. Which is it? Perhaps both.

People of faith know—they have witnessed it. Faith does move mountains. But they also know this: Faith’s power can lay dormant until it’s set ablaze by love. Perhaps only love has the power to fortify faith enough to make the earth quake.

Anger can shake earth, but it cannot move it. Rage can break earth, but it cannot move it. What if faith the size of a mustard seed requires the force of love to move the mountain? If that is the case, we are left with one haunting question: Why have we seen so few mountains move in our lifetime?

FAITH-ROOTED Organizing: Mobilizing the Church in Service to the World outlines a theological cartography of social change. In this critical intervention, Alexia Salvatierra and Peter Heltzel reimagine—and as a necessary consequence, rechart—the landscape of vision, action, and strategic planning needed for social change.

Full disclosure: I have attended several trainings conducted by the co-authors. Indeed, the dual authorship of the text is a principal strength. Faith-Rooted Organizing blends the voice of an evangelical-activist theologian in Heltzel with the homespun profundity of a seasoned pastor and campaign organizer in Salvatierra. The authors delight readers with complementary writing styles: Heltzel speaks through theological propositions, interpolated intermittently with jazz references and theological punch lines; Salvatierra communicates through proverbs, organizing anecdotes, poignant biblical passages, and narrative side notes.

The result is a well-argued and accessible text that should resonate from the seminary to the sanctuary. Their driving thesis is that faith communities, especially Christian ones, should organize for social change in a way that is rooted and guided by the stories, symbols, sayings, and scriptures of our faith. Faith-Rooted Organizing functions as an instruction manual on effective advocacy while providing a theological rationale and vocabulary for a vocation marked by tremendous victories and colossal failures, breakthrough partnerships and fragmented coalitions, glimpses of beloved community and portraits of democracy stillborn.

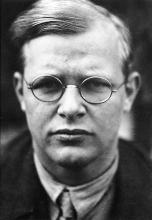

A new biography is raising questions about the life and relationships of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, an anti-Nazi dissident whose theological writings remain widely influential among Christians.

Both left-leaning and right-leaning Christians herald the life and writings of Bonhoeffer, who was hanged for his involvement in the unsuccessful plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler in 1944. Bonhoeffer was engaged to a woman at the time of his execution, observing that he had lived a full life even though he would die a virgin.

The new biography, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, from University of Virginia religious studies professor Charles Marsh, implies that Bonhoeffer may have had a same-sex attraction to his student, friend and later biographer Eberhard Bethge.

“There will be blood among American evangelicals over Mr. Marsh’s claim,” Christian Wiman, who teaches at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music, wrote in a review for The Wall Street Journal. But there’s been no bloodbath yet, at least considering a few initial reviews.

We’re headed home from Wild Goose Festival, a gathering of artists, activists, musicians, and theologians, in Hot Springs, N.C. It was hot, rainy, and messy. My suitcase smells like my fifth grade gym locker.

I can’t wait to go back next year.

The speakers are remarkable; many of them are walking the talk they’re offering, which is an unfortunately rare phenomenon. The music is fresh and exciting, the art is created before your eyes, and there is an energy of hopeful expectation that renews your soul, flushing out the broken-down-ness of daily life.

But the most important part of the whole four-day event lies in the unexpected moments. Sometimes I would walk along the main dirt road in the middle of the grounds, lined with tables, tents, and makeshift gathering spaces, until I saw something interesting going on and just joined in.

In one moment you’re debating the theological implications of the American food-industrial complex. Half an hour later, you’re laughing with new friends in the beer tent. And then, just when the sun sets and you’re sure you lack the fortitude to go one any more, the music on the main stage cranks up and the very earth beneath you vibrates.

I have two daughters.

They are little spark plugs of utter joy and complete chaos. They make me laugh. They make me cry. They remind me to view the world through childlike wonder. They remind me that I am not what I do, but who I am. They teach me what selfless love actually looks like … every day … day after day … early morning after early morning … nasty crap diaper after nasty crap diaper. They make me realize how much I have to learn about parenting and our place in the world.

Most every night from the moment they were born, I have quietly held them in my arms or rested my hand on their backs while they sleep and prayed for them.

I pray for their continued breath. I pray for their development as little, unique human beings. I pray the Spirit of God to fill them and empower them. I pray the Lord’s Prayer over them. I pray for them to be protected from evil. I pray for them to love those who aren’t often loved. I pray for them to live confidently into who they have been created to be, free from the pressure of imposed reputation and expectation.

I pray for their past, present and future.

In learning to love these little girls, I began to ask more and more questions about the place of women in the world, in the church, and in everyday life.

… my cup overflows.

-Psalm 23

Women have a lot to offer — and the problem is that we offer it too often and too long and without a break to fill the fountain. Women, at all ages, even girls, are set up to please and to give. Pleasing and giving are wonderful things — especially if they are appreciated and if they matter. When a womb is a fountain it overflows into goodness. When a womb is disrespected and unappreciated, even it can go dry.

I think of my two grandmothers: Lena and Ella. One was generous, the other stingy. One stretched the soup, the other made sure it was thick for her inner circle. One died happy and the other died sad. You may think I’m going to suggest that Lena, the generous, died happy and Ella, the less so, died sad. The truth is both had a certain joy and a certain regret. Women who give a lot to others often wonder when it will be their turn. Women who are as selfish as men with soup and self get hurt less. Women know we are “supposed” to keep the beat and feed the family. We also experience compassion fatigue, time famine, and wonder when what we give will come back to us. We worry that our fountains will go dry.