Faith

Theology doesn’t save us from spiritual burnout — people do.

No matter how convincing our doctrines and beliefs may be, they’re ultimately empty and unsatisfying if there’s no human relationship personifying them.

Throughout our faith journeys we’ll be faced with moments of suffering, hopelessness, and sheer desperation — sometimes lasting for what seems like forever. We’ll want to give up — sometimes we will.

These hardships can devolve into isolation, bitterness, and ultimately transform what was once a healthy spirituality and turn it into a total rejection of God. Within Christian culture we label this as “burnout,” but in reality it’s more of a “falling out.”

Not only do we have a falling out with God, but we also disassociate ourselves from other believers and those closest to us. When we feel hurt, betrayed, or abandoned by people we assume God is to blame, causing us to doubt God’s love for us — even questioning God’s very existence.

Many quit faith not because of a newfound disbelief in God, but because of broken and unhealthy human relationships — people are the main reason we give up on God.

"Then the LORD said, 'I have observed the misery of my people…I have heard their cry…Indeed, I know their sufferings…’ - Exodus 3:7

For the last few weeks, the eyes of America have been riveted on the town of Ferguson, Missouri, a formerly little-known suburb of St. Louis. It was there on Aug. 9 that an unarmed African-American teenager named Mike Brown was shot six times by police, sparking ongoing protests and demonstrations by grief-stricken and outraged citizens. Clashes between demonstrators and heavily armed local police, highway patrol, and the Missouri National Guard have been the subject of extensive coverage and all manner of commentary across broadcast and social media.

These demonstrations in Ferguson represent something more than just lament for the tragic death of Mike Brown. They are an outcry at the demonization of black men, racial profiling, institutional racism, intergenerational poverty, the militarization of law enforcement, and a culture of incarceration in America. Over the last three weeks, Ferguson has become a flash point for urgent issues facing minority communities, issues which have been largely unnoticed or ignored by the majority white culture. The #Ferguson hashtag no longer just refers to the events happening in Ferguson but has come to represent a national conversation about the toll that institutional racism and its many diabolical expressions have taken on our fellow Americans.

In the days following Mike Brown’s death, columnist Leonard Pitts, Jr. described the protests as “an act of outcry, a scream of inchoate rage. That’s what happened this week in Ferguson, Mo. The people screamed.” These screams echo of the cries that God heard from the Hebrews enslaved in ancient Egypt.

Editor's Note: Spoilers ahead! You've been warned.

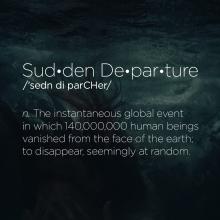

Over the past eight episodes of The Leftovers, HBO’s latest drama based on Tom Perrotta’s play of the same name, viewers have been treated to a case study in grief and faith in the midst of a life-changing event. Unlike the Left Behind series, which incorporated Christian triumphalism with terrible theology, The Leftovers examines the deeper human and spiritual issues of what would happen were two percent of the population to suddenly disappear. It is powerful and beautiful and really hard to watch (especially Episode Five). It asks the question: does life go on when your world is changed forever?

The show offers a variety of responses to the Sudden Departure of October 14: Kevin Garvey, the police chief who seems to be losing his mind after his wife leaves him for a cult and after his father needs to be committed; Nora Durst, who’s lost her entire family, so she keeps everything exactly as it was when the Sudden Departure occurred; Rev. Matt Jamison, Nora’s brother whose faith has been shaken because he was not taken; the town dogs who have become feral; and finally, the creepiest citizens of Mapleton, the Guilty Remnant, or the GR as they’re “affectionately” known.

This past week’s episode gave us a greater understanding of the GR. Although the nihilistic views of the Guilty Remnant are quite different from those of Christianity, I was struck by their powerful and strategic mission of witness. The cult was formed out of the recognition that everything changed on October 14 and that to pretend otherwise was foolish. The group, in their white clothes, their silence, their stripped-down existence, bears witness to the fact that they are living reminders of what happened. They are fundamentalists about their cause and willing to die for it — even if that death comes from their own hands.

It was the beauty on the outside that drew me away.

Before social justice became trendy among evangelicals, people of all denominations, faiths, and philosophies had already been steadily working in the trenches without fanfare, caring for the least of these with a quiet strength.

Through seminary, I learned to grapple with justice being at the heart of the Christian Gospel — dignity, equality, and right to life for all — I marched out into the real world with zeal and vigor to champion the rights of the oppressed in the name of Jesus. However, I discovered the people who were doing this work often had no identification with Christianity, that those outside of church were behaving more Christian-ly than some inside.

I admired Nicholas Kristof, a self proclaimed nonreligious reporter, who tirelessly sheds light on humanitarian concerns.

I adored Malala, a Muslim, who stood up to the Taliban to bravely demand a right to education for girls.

I reflected on the justice heroes of recent history, people like Gandhi and countless other humanitarian workers who don’t claim the Christian faith for their own.

It disoriented me because for so long I believed it was only through Christ that one can walk in righteous paths; that without the Truth (which had been so narrowly summed up for me in John 3:16), everything was meaningless. I didn’t have an interpretive lens to categorize beauty that existed outside of the vessel I was told contained the only beauty to be found: the evangelical Christian church.

I don’t know about you, and the people you know, but most people I know who call themselves Christians are particularly proud of the certainty that they are ‘good enough’.

It’s an odd phrase when you think about it; in a world simmering with chaos, injustice and upheaval, oppression, poverty and human trafficking, in our cities filled with addiction and unrest, our prisons cramped and over-flowing, do any of us really believe that the best we can do is ‘good enough’?

Can many of us actually congratulate ourselves, or our faith communities for our impact on our neighborhoods, schools or cities?

According to one of my favorite authors, Brennan Manning, "The single greatest cause of atheism in the world today is Christians, who acknowledge Jesus with their lips, then walk out the door and deny Him by their lifestyle. That is what an unbelieving world simply finds unbelievable." It is just a much more eloquent way of saying that the world thinks we’re a bunch of hypocrites.

To be quite honest, most of the time, the claim is warranted. I have a friend who wants nothing to do with Jesus because his father, a very religious man, was active in the local church but was abusive behind closed doors. Another friend continues to distance herself from anyone associated with the church because of their judgmental glares about her lifestyle choices.

Whatever their reasoning, I understand. I, too, have personally encountered the hypocrisy they see in our communities of faith. And if I'm at all honest, the number of times I have been the hypocrite who has turned others away are too numerous to count.

I was privileged to attend the ordination of a friend recently. For the first time, Michelle got to say the blessing over the bread, to break the bread and to give it to all of us with her hands.

Many tears, much joy.

As she handed me a small piece of the bigger loaf, I was reminded of how we, like the communion bread, are in the hands of others for so much of our lives. And how religion can be a thing of so much good or so much pain, depending upon whose hands it is in.

In the right hands, it’s a pathway to the divine. In the wrong hands …

It’s important that we always differentiate between religion and God. The two are distinct. God is always much bigger than any and all of our religions.

I went to the mecca of evangelicalism for college — beautiful campus in the suburbs of Chicago, where I received a scholarship from none other than the Pope of Evangelicalism, Billy Graham, for my work in street evangelism. As in, speaking to random strangers on the street in order to convert them to Christianity. Post graduation, I became a missionary, the Protestant equivalent of achieving sainthood.

I look back on that girl on fire and marvel at her earnest faith. If I could, I would reach back and massage the tense knots out of her high-strung shoulders, weary from carrying the weight of her neighbors’ eternal destinies. I would wistfully explain to her that the first person she tried to witness to, that gentle, drunken, homeless woman named Kathy, needed more than my rehearsed Roman Road to salvation. Then I would break the Temporal Prime Directive and reveal to her that one day she would become more interested in being evangelized than evangelizing.

The truth is, I’m just better at being evangelized. It’s probably how I was so easily converted at the tender age of 12. The young Christian is expected to learn how to share their testimony: their story of how God changes your life. By the time I was in my twenties, I had given my testimony a bajillion times.

But my own story often bored me.

PRIOR TO MY conversion to Christianity, I was the roving reggae reporter for High Times, a magazine dedicated to marijuana culture. I also wrote music reviews for NY Press, Virgin Records, and various other publications.

One of my favorite artists from the early 2000s was Cody Chesnutt (he spells his name with two capital Ts at the end), an independent recording artist popularly known for his hit song “Seed 2.0,” a soulful rock and hip-hop hybrid released in 2002 with The Roots.

Chesnutt’s musical debut was a lo-fi soul and rock-and-roll album titled The Headphone Masterpiece. It was a double disc (this was still the heyday of compact discs) that he recorded on a 4-track recorder in the bedroom of his Los Angeles apartment. He played all the instruments—guitar, bass, keyboard, and organ. The sound quality and lyrical content are both intentionally gritty.

Headphone quickly became the soundtrack to my college years. I was a reveler, filled with hypersexual bravado and abundant egotism, and Chesnutt’s music reinforced and undergirded my misdirected youthful zeal. His lyrics were unrepentantly misogynistic, and his strong sense of self pervaded each track. He exploited his infidelity and womanizing in his music, at times in a prophetic way, such as in “My Women, My Guitars,” which he opens with incredibly crude lyrics, but later croons with utmost vulnerability: “Man, something’s been killing me. My women, my guitars. I’ve been living hard. My breakdown is on the way. I know my breakdown is on the way. So I get up on my feet. Falling back on my knees to pray.”

Faith: dealing with the meaning of life, the matter of eternal salvation — the bedrock upon which we build our families and society. This is serious stuff. Irreverence, by definition, is a lack of respect for that which is serious. It would seem that finding faith in the irreverent is impossible, like searching for the sun in the dark of the night.

Irreverence permeates pop culture. From HBO shows filled with crude nudity and violence, to musicals such as The Book of Mormon (where explicit ratings are applied to almost every song), to late night comedies featuring popular hosts like Jon Stewart and Colbert, who play-act a persona speaking exclusively in snark.

The Church, by and large, keeps irreverence at arm’s length. Sure, some pastors like to open sermons with a couple of clean jokes, but that’s about the extent to which humor interacts with the Faithful. While I agree there’s a social maturity required in expressing irreverence through appropriate channels, the Church is missing out on a deep authenticity of the human experience if we continue to fear irreverence instead of finding beauty in it.