Faith

Editor's Note: Sojourners has launched this new blog series to help shed light on the nation's latest "religious" affiliation. Scroll down to read their stories. Or EMAIL US to share your own.

Which religious tradition do you most closely identify with?

- Protestant

- Catholic

- Mormon

- Muslim

- Jewish

- Orthodox

- Other Faith

- Unaffiliated

Given these options — or even if you throw in a few more like Buddhist, Hindu, Agnostic — I would choose “Unaffiliated.” That puts me into a category with one-in-five other Americans, and one-in-three millennials, aptly named the “nones.”

In that vein, I introduce our new blog series: Meet the Nones. Through this series, I hope to encourage discussion, debate, and elucidate the full picture of what it means to be losing your religion in America.

Editor's Note: Would you like to share your story on this topic? Email us HERE.

BEND, Ore. — State labor officials have ordered a dentist to pay nearly $348,000 to settle allegations that he threatened to fire a dental assistant unless she attended a Scientology-related training session.

The Bureau of Labor and Industries contends Dr. Andrew W. Engel repeatedly "badgered" Susan Muhleman about the three-day conference despite her concerns that it would conflict with her Christian beliefs. He also turned down her request to attend secular training instead, investigators said.

As a result, Muhleman quit AWE Dental Spa in August 2009 — weeks before the conference — and moved out of state to find a job, the state agency said.

Muhleman said she was opposed to going to the Scientology conference but worried about losing her job at the height of the recession, when the local jobless rate was about 15 percent.

For Nathan De Lee, going to church as a kid was an ordeal.

De Lee, a Unitarian Universalist, grew up in rural Kansas, where members of his faith were few and far between. Attending services meant an overnight trip to Kansas City, Mo., where the nearest Unitarian Universalist congregation was.

Today, getting to church is easy for De Lee, an astronomer at Vanderbilt University. He's a regular in the choir on Sundays at First Unitarian Universalist Church in Nashville, which has a congregation of about 500.

De Lee is one of a growing number of Unitarian Universalists, a group of people who believe in organized religion but are skeptical about doctrine. The denomination grew nationally by 15.8 percent from 2000 to 2010, according to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies.

EVEN IN AN age of ever-faster news cycles and shorter word counts, some journalists still find ways to dig deep into research and reporting to bring history to life and lift up voices that might otherwise be unheard. Here is an eclectic mix of nonfiction works on issues and people that matter.

Can those who commit violent crimes ever truly be rehabilitated? What happens to them once they’re out of prison? In Life After Murder: Five Men in Search of Redemption (PublicAffairs, 2012), Nancy Mullane follows her subjects from prison to welcome-home parties and beyond. While never minimizing the crimes her subjects have committed, she portrays their full, complicated humanity. Moving insights about the ongoing spiritual, emotional, and practical work of accepting responsibility for great wrongs and rebuilding a life after prison are framed by reporting on the convoluted, expensive prison and parole policies of California.

You might not expect gripping drama from a writer specializing in U.S. Supreme Court history, but that’s what Gilbert King’s Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America (Harper, 2012) delivers. Long before he became a Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall was an NAACP lawyer who risked his life travelling to the Jim Crow South to defend African Americans accused of capital crimes. Devil in the Grove describes his efforts to save a black citrus picker from the electric chair in a Florida county where the Klan and law enforcement were brutally intertwined—and brings alive an era of domestic terrorism against people of color in the not-distant-enough past.

[editor's note: This article was originally published in 2012. References to elections or politicians without specific dates attached are in the context of the 2012 election cycle.]

AS I CAREFULLY watched both the Democratic and the Republican conventions this summer, I realized, once again, how challenging and complicated it is to bring faith to politics.

For example, the phrase “middle class” was likely the most repeated phrase at the conventions. And even though both parties are utterly dependent on their wealthy donors (a fact they don’t like to talk about), they know that middle-class voters will determine the outcome of the election. Now, I believe a strong middle class is good for the country, but Jesus didn’t say, “What you have done for the middle class, you have done for me.” Rather, Matthew 25 says, “What you have done to the least of these, you have done to me.”

When your first principle for politics is what happens to the poor and vulnerable—and I believe that is the first principle for Christians—you keep waiting at conventions for those words and commitments. There were a few moments when the poor were briefly mentioned, but it certainly wasn’t a strong theme in Tampa or Charlotte. “Opportunity” for the middle class was an important word in both conventions this year, but Christians must be clear that creating new opportunities for poor children and low-income families is critical to us.

The conventions also talked a great deal about “success,” but how we define that is very important. Is success mostly about how much money we make, defining the “American Dream” as being able to pass on more riches to our children than what our parents passed on to us? Or is success measured by how we as a nation prioritize, in our spending and political choices, the sick, the vulnerable, the weak, and the elderly? Is it determined more by the values we pass on to our children—evaluating our lives, and theirs, by how much we are able to help others?

America is a nation of immigrants, and how we welcome “the stranger” in our midst is another Christian principle for politics. So is our racial diversity as a nation, where all our citizens must be treated as having equal value. The most inspiring stories at the conventions for me came when that diversity was evidenced on the stage—from a young undocumented “dreamer” and a black first lady on the platform at the Democratic convention to Condoleezza Rice telling her fellow Republicans how a little girl from a segregated Southern city became secretary of state. But little mention was made at either convention of the racial disparities in America’s burgeoning prison industry or voting suppression efforts that most affect minorities and people who are poor.

My neighbors signed my report card.

Having had the same conversation countless times in my life, I have learned that one sentence sums up a cacophony of explanations.

It is tricky, I have found, trying to explain why friends are listed as my emergency contacts, why I wake up Christmas morning in the home of people to whom I am not related, and why my parents — both living — have been anything but.

The separation started so long ago that I struggle to remember exactly when it began. When I was starting middle school my mom’s depression hit hard and fast. My dad, who understands love as a finite commodity, could not muster any for me. Loving her meant giving all of it to try to save her. His attempts and inability to do so created a stress that amplified his MS from inconvenient to disabling.

In a moment, it seemed, they were gone.

We were wealthy and Southern and had everything that went along with both: a close-knit community, punctilious social obligations, and money to stay afloat. In the world in which I grew up, everyone surely knew everything about everyone, but damn if they weren’t polite enough to pretend it was all OK. It was a magnificent masquerade.

But the truth remained: I was an orphan.

ASSISI, Italy — Swimming against a global tide of religious violence and political polarization, about 550 religious and humanitarian leaders met recently here in the birthplace of St. Francis to propose a new way forward: love and forgiveness.

The ambitious aim of the Sept. 19-23 “Global Gathering” was nothing short of putting those values to work in some of the most hate-filled and unforgiving places on Earth. Following the example of Francis, whose feast day is on Thursday, participants pledged to make lofty ideals real through dozens of creative projects researched and funded by the Michigan-based Fetzer Institute, the conference convener.

“There’s a power in love that our world has not discovered yet,” said Fetzer President and CEO Larry Sullivan, quoting the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Let’s put our backs into the work of love and forgiveness.”

I’m Catholic. My father comes from a working class Irish Catholic family; my mom is from a large Catholic family of German and Lithuanian decent. My brothers, sister, and I all attended Catholic school and growing up we attended Friday fish fries during Lent and church polka fests in the summer. I’m an active member of a Catholic church in St. Paul. And soon, my wife and I will celebrate the baptism of our daughter into the Catholic Church.

I’m also voting no on the anti-marriage and voter restriction amendments.

Some have asked how I can embrace a faith whose leadership has taken such a hard line against gay and lesbian equality, and which is painfully quiet on the threat to limit voting rights. I understand why people ask this question. For me, my decision to vote no is not in spite of my Catholic faith, it’s because of it.

When I was 10 my parents divorced. A couple years later my mom came out to my family as lesbian. By then she no longer felt welcome at church and stopped going to mass, though she has remained a deeply spiritual person. This one case of social exclusion is deeply meaningful to me, but is nothing compared to political decision by church leadership to spend millions of dollars to limit the freedom to marry in Minnesota. By doing so church leaders seek to permanently exclude gays and lesbians from the civil rights and benefits straight couples enjoy.

But here’s the thing: I’m still getting my daughter baptized. And I’m still Catholic. And I’m still voting no on both amendments in November.

For most of my life, I have been a “Christian with conjunctions.”

So I’m a Christian BUT… I’m not like that street preacher who yells about hell and damnation on the downtown corner.

I’m a Christian BUT I’m different from the televangelist who raises his fist in the air and screams about salvation.

My own priest, the Rev. Thomas Murphy, first described himself as a Christian with conjunctions in a sermon the morning before our Episcopal congregation took to the streets during a festival in downtown Asheville, N.C. Across the street from a karaoke booth, we handed out cold water to festivalgoers and offered a simple ministry with no judgment or obligation.

For most of us, it was the first time we had prayed the Eucharist in public, with our colleagues, students, and neighbors walking past. The white banner above us proclaimed: “God loves you. No exceptions.”

I have realized that the ubiquitous street preacher has something to teach me: there is virtue in being bold about my faith. Through my research on congregations and climate change, this public witness to God’s love has become easier for me as my church life now reflects my deep value of God’s good earth.

The stakes of silence are high. If we don’t speak out and act on our moral mandate to reconcile with creation, we risk destroying God’s very creation.

“Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

~ Arundhati Roy

Vegetables.

Who could have imagined an economy in which gentle vegetables were subversive?

But this is our world. A world where a vegetable, whose growth is imperceptible to the naked eye, can spider a crack into the concrete of our industrial food system.

We find ourselves in a food economy that sickens us. Health is divided along race and class lines: the food economy particularly sickens those whose wages do not allow them to buy the foods that can cure us of the diseases industrial “foods” cause.

Corporations, which do not speak the language of human love and health, wrangle to profit from the stream of ill Americans falling from the industrial foods conveyor belt. But we know that type 2 diabetes, heart disease, obesity, and some cancers are fully preventable by replacing part of what we eat with fruits and vegetables.

Why, in a wealthy, fertile country are we wrecking the environment to produce foods that kill us?

This past Saturday, on a brilliant fall morning, my eight-year-old son came bounding downstairs for breakfast. I reached into the refrigerator, grabbed a cold Diet Mountain Dew from in between glass-bottled organic milk and tomato juice, and served it to him with farm-fresh eggs, feeling the part of a drug dealer.

We had a long day ahead, and I wanted to see what happened.

I smiled to myself, imagining some upcoming event, the mothers’ conversation all about peanut-free this and local that, when I’d pipe above the crowd to say, Hey sweetheart, how about your Mountain Dew?

The arrival of Diet Mountain Dew in my house is only the first in a cascade of little experiments we are now undertaking as a result of neuropsychological testing in August indicating that my son has a form of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Our house has never lacked order or discipline, and yet now we are thinking about how to structure everything more explicitly.

Diet Mountain Dew, with its massive amounts of caffeine, is our initial effort in our goal of avoiding, for now, giving him any stimulant medications: Did you know that caffeine actually calms down a hyperactive person, allowing them to focus? Maybe that’s why I’ve drunk eight cups of coffee every day since around 1985.

I tried the coffee with my son first, hoping I could cultivate a new bond with him over a shared habit. He detested the stuff. You could always give him Red Bull, one of my brothers said. I couldn’t bring myself to do that, hence the Diet Mountain Dew.

A couple days ago I called my friend Kae so we could talk about this Gospel reading where Jesus takes a child in his arms and teaches the disciples that if they welcome a child in his name they welcome God. And we started talking about the actual reality of children and how difficult small ones can be to manage. Kae told me of this brilliant technique she employs when dealing with toddlers.

She said it really helps her to be patient and compassionate with defiant, emotional, snot-faced toddlers when she just thinks of them like little versions of really drunk friends. Then when they keep falling down and bumping into things and bursting into tears she just treats them like she would a friend who is too drunk to know what they are doing, and who you just try and make sure doesn’t hurt themselves, and who you clean up bodily fluids from, and make sure they drink some water, and then just lovingly change them into their pajamas and tuck them into bed.

Children are really a mess.

We’ve all heard the rhetoric. “We need to take America back for God!”

Why? Supposedly so we can regain some bygone level of ethics or moral standards. Supposedly, if we don’t, God will get tired of us “rebuking” God and remove God’s hand of protection from us. Supposedly, so God won’t test us or judge us or something.

Yet, as Gregory A. Boyd notes in his important book The Myth of a Christian Nation: How the Quest for Political Power Is Destroying the Church, taking America BACK for God assumes we were at one really belonged to God, followed God, listened to God. Boyd goes on to ask, when was this glorious age in the history of the USA?

Let’s start way back. We’ve been taught that many people migrated to North America for religious freedom. So was this glorious time when some of our forebears imprisoned, tormented, and/or hanged many suspected to be witches? Is that what so many want to take us back to?

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the United States currently spends more than $711 billion per year on military expenditures, which is – by far – the most of any country in the world.

In fact, if one were to combine the totals of the next fourteen nations on the list (China, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Japan, Saudi Arabia, India, Germany, Brazil, India, South Korea, Australia, Canada, and Turkey), their combined amount is similar to the USA. All together, the USA provides about 43 percent of worldwide military costs, and in addition, the USA per capita ($2,240) and percent of Gross Domestic Product (4.8 percent) in relation to military funding is far greater than any other nation in the world.

With these statistics in mind, one is provoked to ponder some important questions. For example, what is revealed to us about the USA – and our world in general – when military expenses constitute such a significant percentage of a government budget?

In specifics, why does the USA spend far more on its military than any other country? In addition, what is revealed to us about the condition of our global village when $1.73 trillion is allocated each year to military funding? As stated by Sojourners CEO Jim Wallis, “A budget is a moral document. It clearly demonstrates the priorities of a family, a church, an organization, or a government. A budget shows what we most care about.”

Cheerleaders at an East Texas high school are fighting their school district’s orders to stop using Bible quotes on their signs at football games.

In August, cheerleaders at Kountze High School, a school with fewer than 500 students 30 miles north of Beaumont, Texas, began painting Bible verses on large paper signs football players burst through at the beginning of games.

But this week, Kountze Independent School District Superintendent Kevin Weldon called for an end to the banners after consulting with a legal adviser at the Texas Association of School Boards.

“It is not a personal opinion of mine,” Weldon told KHOU, a Houston television station. “My personal convictions are that I am a Christian as well. But I’m also a state employee and Kountze ISD representative. And I was advised that such a practice would be in direct violation of United States Supreme Court decisions.”

That prompted the cheerleaders and their supporters to launch a Facebook page, “Support Kountze Kids Faith,” which attracted 34,000 members in its first 24 hours — more than 10 times the population of Kountze.

Parents of at least three cheerleaders have hired an attorney and are considering suing the school district.

I’ve been reflecting on the recent events in Libya involving the death of Ambassador Chris Stevens, and every time, I arrive at a different feeling about it all.

There’s the obvious tragedy of a life unnecessarily lost. By all accounts, Stevens was a humble, passionate man who had invested his life in the betterment of the infrastructure for the Libyan people. He was not, as some dignitaries or diplomats tend to be, resting on his credentials in an easy gig, waiting for retirement. He was living out what he believed in a terribly volatile corner of the world.

Jacques Berlinerblau wastes no ink in his new book trying to flatter his fellow nonbelievers.

"American atheist movements, though fancying themselves a lion, are more like the gimpy little zebra crossing the river full of crocs," he writes in How to Be Secular: A Call to Arms for Religious Freedom.

Ouch.

"In terms of both political gains and popular appeal, nonbelievers in the United States have little to show. They are encircled by cunning, swarming [religious] Revivalist adversaries who know how to play the atheist card."

Berlinerblau, a Georgetown University biblical scholar who teaches a course on secularism, wants to rescue that little zebra. But his plan may be a hard-sell with some atheists — he wants atheist groups to drop their black-and-white opposition to religion and its adherents in order to preserve the Constitution's guarantee of freedom of religion.

"The gimpy zebra remark was a little goofing on this over-the-top chest-thumping that emerges from Movement Atheists," he said in an interview, referring to atheist organizations with political goals, like American Atheists. "They wildly overestimate their numbers. They tend to overestimate the efficacy of their activism. They underestimate how disciplined and organized their adversaries in the religious right are, too."

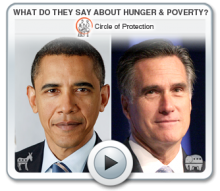

Christian leaders asked, and the presidential nominees answered. The poverty rate in America is still at a staggering 15 percent and 46.2 million Americans remain in poverty — what is your plan to address the problem?

The Circle of Protection, composed of Christian leaders from across the religious spectrum, released President Barack Obama's and GOP nominee Mitt Romney's video responses today at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C.

(VIDEOS from Obama and Romney after the jump.)

Good and gracious God,

Today we come before you with heavy hearts

as we remember the events of 9/11.

For some of us today is a mixed bag of emotions.

We hurt deeply for those who lost their lives

and those who lost their loved ones.

We mourn the nearly 3000 who died that day.

We are humbled by the bravery of the first responders.

We continue to grieve with our neighbors

in the loss of our national innocence -

our false sense of constant safety.

Out of the chaos, to the rhythm of the Lord’s Prayer, John Mahony, a retired U.S. Army colonel who was managing projects for Blue Cross/Blue Shield, sensed something that reminded him of when his mother would wrap him up as he’d climb out of a cold swimming pool, and he would be held, safe and warm, in loving arms.

“As I walked down that stair, somewhere between the 12th floor and the 10th, somewhere between ‘Our Father’ and ‘Thy will be done,’ that same feeling came over me," Mahony said. "Suddenly, I was wrapped in warmth, and love, and comfort. In that smoky, wet stairway, in a burning building, surrounded by a thousand frightened people; I felt wonder. I felt God’s peace, and I knew that regardless of the physical outcome, everything would be all right.”