Sep 10, 2012

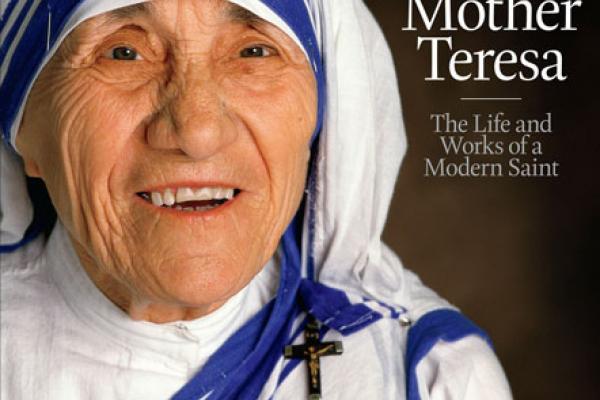

On Sept. 5, 1997, the world mourned when Mother Teresa, whose work with the poorest of the poor made her a global icon, died of a heart ailment at age 87.

Exactly 10 years later, the world did a double take, when a volume of Teresa's private letters revealed that the tireless, smiling nun spent the last 39 years of her life in internal agony. Jesus, she wrote, no longer seemed present to her, in prayer or even in the Eucharist. In letter after tormented letter she described an unrelenting spiritual "dryness,” a "torturing pain." Her smile was "a big cloak" of deception. She admitted at one point to doubting God's existence. Eventually she apparently became more reconciled to her condition; but as far as we know, she died with it.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login