creation

St. Bonaventure (d. 1274) once said, “Whoever is not enlightened by the splendor of created things is blind; whoever is not aroused by the sound of their voice is deaf; whoever does not praise God for all these creatures is mute; whoever after so much evidence does not recognize the Maker of all things, is an idiot.”[1]

If Bonaventure was right, then we’re all idiots.

The first time I travelled to Rome was an experience second to none. Never, in my young travels, had I ventured to a place so layered with history and significance around every corner that one literally couldn’t escape it. Even the Roman suburbs were historical. We were amped to see it all. Our approach was simple: we would incrementally make our way through the city over the course of 10 days with a plan that would make any explorer proud.

The sheer magnitude of historical and ecclesiastical sites to be seen in the city was overwhelming at best. Then it happened. I had a unique moment near the end of the trip. We’d been walking nonstop through museums, ruins, churches; we’d even heard the pope preach a sermon, when I started to lose my attention. Many travelers or art buffs will resonate with this — there came a point during our endless walk through Rome where I had seen so much beauty and splendor and history that I just started taking it all for granted. The last two days consisted of me walking around blindly and numbly, room-to-room, ruin-to-ruin, as though what I stood before was of little or no value.

I called it “beauty exhaustion.”

From white villages Easter bells resound.

Rejoice! Give thanks! I raise my voice

Evil disappears from the world.

And that means somewhere God must be.

Andrew Bird is one of my favorite musicians. I love the way he makes a one-man band, looping over his own violin playing, singing, whistling, and stomping to create beautiful songs. No two live performances are the same. And once, when I saw him in D.C., he played a new song that was still being written — one that had come from his heart, but he hadn’t yet finished and didn’t think it had an end.

He told us he wrote the song during the BP oil spill, often called “Deepwater Horizon,” that happened in the Gulf of Mexico. During that disaster, over 200 million gallons of crude oil spewed into the Gulf for days on end from a hole nobody could plug, and the whole country watched it happening live.

Last Sunday in Los Angeles, Cathleen Falsani sat down with Ari Handel, a screenwriter and frequent collaborator with Noah director Darren Aronofsky, with whom he co-wrote the film and the graphic novel, Noah, upon which it was based, to discuss some of the extra-biblical elements of the $150 million movie.

Longtime friends Handel and Aronofsky were suitemates at Harvard University. Before becoming a screenwriter and film producer, Handel was a neuroscientist. He holds a PhD in neurobiology from New York University. He was a producer on Aronofsky’s films Black Swan, The Wrestler, and The Fountain (which he co-wrote with Aronofsky), and had a small role as a Kabbalah scholar in the director’s debut film, 1998’s Pi.

Editor’s Note: The following Q&A contains some spoilers about the film. It has been edited for length.

Last fall, on a Sunday afternoon, as I walked out of the church, a young man tugged on my Franciscan habit. It was Miguel, a member of our Latino choir.

“Father,” he said, “please, pray for the people of my home parish back in El Salvador, especially for one of the priests who has received death threats.”

Startled, I asked: “What is happening there?"

“These priests are organizing against the multinational companies,” he said. “The companies are looking for gold. What will be left for our people? Only poisoned water, a wasteland, and death.”

A few weeks later, I had another similar conversation with a group from Guatemala. Theirs was a similar tale of how indigenous communities were being threatened by mining projects.

As a Catholic and a member of the Franciscan Order, I believe that we are called to “read the signs of the times” and to listen to the cry of the poor and the “groaning” of God’s Creation.

THE STILL, ATTENTIVE, affectionate, at times lamenting, always sagacious, well-defined, occasional poems in This Day, Wendell Berry’s most recent collection, are a magnificent gift to American letters.

For nearly 35 years Berry has kept the Sabbath holy. His practice is either unorthodox or so deeply orthodox that professional religionists may not recognize it. On Sundays Berry walks his Kentucky “home place,” the roughly 125 acres of bottom land in the region his family has farmed for more than 200 years. From the seventh-day silence, solitude, and natural world, Berry has crafted his Sabbath poems.

“Occasional poems” commemorate public events, but here Berry lays quiet markers to remember personal days in the life of one man. He writes in the preface: “though I am happy to think that poetry may be reclaiming its public life, I am equally happy to insist that poetry also has a private life that is more important to it and more necessary to us.”

A new film charting Charles Darwin’s passage from Christian to nonbeliever propelled its maker on a similar journey.

“Questioning Darwin,” a new, hourlong documentary airing on HBO throughout February, juxtaposes the story of the 19th-century British naturalist with looks into the lives of contemporary American Christians who believe the world was created in six days, as described in the Book of Genesis.

Antony Thomas, the 73-year-old British filmmaker behind the camera, said while his goal was to highlight the way his subjects answered big questions about the origins of life, a loving God, and the purpose of suffering, he found his own answers to those questions changing.

“This is a personal feeling, but I do believe the two [a belief in God and in evolution] are not compatible,” Thomas said by telephone from New York, where he is working on another documentary. “And that is what made this worthwhile for me.”

Whenever I hear about someone else making a case for Young Earth Creationism in the name of Christianity, I’m embarrassed, once again, to associate myself with them. And people wonder why many of us prefer to identify as “Jesus followers” or “Spiritual but not Religious” rather than be lumped in with the Ken Hams of the world.

Duh.

The thing is, a healthy number of us who consider ourselves to be Christian embrace science. We think critically. We accept the likelihood that much we think we understand about the world, the universe, and about our faith can (and should) change as we learn new things. We understand that faith is more about questions than answers, and that the prime mover in our faith practice is to be more like Jesus in our own daily walk, rather than focusing so much on making others more like us.

The desire of a vocal minority (yes, that’s what I said, and I meant it) of Christians to cling to a notion that the entire universe is a few thousand years old, despite the clear physical evidence to the contrary, points less to a reasonable alternate view of the observable world. Rather, it points to a desperate attempt to maintain a dying voice in the cultural conversation.

Recently, I presented this piece at the Christianity 21 Conference in Denver, and then at South Broadway Christian Church later that same week, also in Denver. I’ve been asked by several in attendance to post what I offered, so here’s the text below. The talk was accompanied by a slide show that depicted a combination of Hubble telescope images, electron microscope images and artists/musicians. I considered making that into a video, with me narrating the text underneath, but it takes a lot of time. So let me know if this is something you have particular interest in and I’ll try to make it happen.

In the Beginning

Art Saves lives because art is at the source of all life.

It is the taproot to the dormant breath of God,

Dwelling within all of creation, waiting for invitation.

What we think of today as art is not art.

It has become another product to be consumed,

Rather than a phenomenon to be engaged,

And experience to we have to submit ourselves to,

Allow ourselves to be changed,

And in doing so, catch a fleeting glimpse of

The author, the wellspring,

The essence of what it means to be a soul draped in skin and bone.

[Poem continues after the jump.]

When you hear about stewardship in church, you probably think of your checkbook. Stewardship is the term we use to talk about financially supporting our churches and organizations. But another holy use of the word involves being stewards of creation.

When I hear the word stewardship, I feel the crunch of snow and branches under my feet. I see the trees and paths of the woods owned by my parents’ best friends, where I spent much of my childhood hiking, hunting, skiing, picking apples, and feeding chickadees out of the palm of my hand. It’s one of the places where I gradually heard my calling to work for the care of creation. And the word stewardship transports me to a specific day in my childhood, walking in the woods with my dad’s best friend, Leo, when he pointed to a tree and said he would have to take it down.

How could he kill a tree? I hassled him; I got indignant. I said that nature should be left alone to do her thing. But Leo explained that I was wrong — he managed the land. It wouldn’t be just fine on its own; rather, it needed his careful eye to manage the trails, cut down sick trees, and hunt deer.

MY MOTHER-IN-LAW wears a bikini. She is 70 years old and decades of gravity have done their work. But she wears a bikini nonetheless, with a devil-may-care nonchalance to what others her age are more inclined to cover in sarongs, ruffles, and cruise-wear.

She’s my hero.

Her okay-ness with her body has a twofold source. First, she’s Finnish. Do you know any Finns? Untouched by the Puritan prudishness that is historically English and North American, they share a continental European lack of modesty concerning the body, but to the extreme. While other Europeans are going topless on the warm and sunny beaches of the French Riviera, the Finns are flinging themselves buck naked from their saunas into the snow. There’s a reason to take off your shirt in the south of France—it’s hot! But why subject your private parts to the crunch and scrape of ice in the dead of winter? I don’t have an answer, even though I live with a Finn who regularly goes in for the naked sauna/snow frolicking thing. But, the point is, Finns are profoundly okay with their bodies.

How does this relate to Christian theology? My mother-in-law is also a devout Christian, and I think her embrace of the bikini as her swimwear of choice goes beyond her Finnish heritage to her biblical understanding of creation. She understands that when it says in the Bible that Adam was formed out of the dirt (adama in Hebrew), that she too is a human formed out of humus and that humus is good. She actually believes that when it says, “God saw all that he had made and it was good,” that means her body as well. It also means mountains and trees and iguanas, but one’s body is a great place to start.

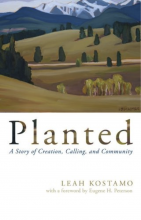

I MET MARKKU and Leah Kostamo of A Rocha, an international Christian environmental organization, on the set of a television show in Toronto. The show was Context, hosted by the welcoming Lorna Dueck. This show explores the stories behind the news from a frankly Christian viewpoint.

I had been invited to talk with Dueck about my MaddAddam future-time book trilogy, and in particular about characters in the second book, The Year of the Flood, called the “God’s Gardeners,” a green religious group that raises vegetables and bees on flat rooftops in slums. It is headed by a man called Adam One and includes a number of ex-scientists and ex-doctors who have withdrawn from a too powerful, greedy corporate world in which they can no longer function ethically. The God’s Gardeners group represents the position—probably true—that if the physical world is going to remain possible for human life, religious movements of many kinds will be an important element. We don’t save what we don’t love, and we don’t make sacrifices unless “called” in some way to make them by what AA refers to as “a higher authority.”

Dueck and I talked a little about that, and then—surprise—right before me were two people who closely resembled the God’s Gardeners of my fiction. Leah and Markku Kostamo are walking the God’s Gardeners walk—through A Rocha, a hands-on creation-care organization. A Rocha’s origins go back to the Christian Bird Observatory (cf. St. Francis) founded on the coast of Portugal by Peter and Miranda Harris in 1983. Leah met the Harrises in 1996 when she took a class they were teaching at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia, and A Rocha Canada was born. It was soon augmented by Markku, an environmental scientist. A Rocha is now running 20 projects around the globe, engaged in everything from habitat restoration to organic community farming.

Many Christians these days are trying to consume less, and they’re doing so for a variety of reasons. For some, in the wake of the economic downturn, thrift is a simple necessity. Others, inspired by books such as Shane Claiborne’s The Irresistible Revolution, Jen Hatmaker’s 7: An Experimental Mutiny Against Excess strive for simplicity for the sake of the health of God’s creation and for the sake of our neighbors, both local and global, who must do without even the basic necessities of life. It’s no secret Americans spend — and waste — a lot.

But how do we begin to consume less? And once we become aware of the horrific conditions under which much of our stuff is made, how do we avoid being overwhelmed by all the injustice that may lie behind our new phone or pair of jeans? And even if we simplify by paring down our wants, what do we do when we actually need to buy something?

Here are some simple strategies to help you live lightly without being overwhelmed by it all.

What would the world be like if we were all more alike?

This isn’t just a philosophical question. In many ways, we live as though we wished others were more like us. We spend time with those who are similar to us and avoid those who seem to be different. We enjoy being around those who share our viewpoint and avoid those who challenge it. We accept the parts of others that make us comfortable and ignore or reject the rest.

But what about our diversity? Do we embrace it, or do we merely tolerate it?

Over time, I’ve grown to appreciate the importance of our differentness. I’ve gotten to the point where I think of this incredible diversity — within our universe, within our human family — as one of our greatest blessings.

The world as we know it may end on Oct. 17.

This statement seems hyperbolic. It sounds like another absurd prediction of the end times that garners far too much attention from the media. But this isn’t about the fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Unless the Congress raises the debt ceiling, Oct.17 is the date that the United States government runs out of money to pay its bills.

The consequences could be catastrophic.

Defaulting on our financial obligations would shatter the global confidence in the U.S. dollar that has made it the worldwide reserve currency. U.S. Treasury bonds would no longer be perceived as safe investments, which means creditors would demand higher interest rates to purchase the bonds because of the increased investment risk. The rise in interest rates would make U.S. debt more expensive to finance, leading to more government spending and slower economic growth. The U.S. Treasury believes a default could cause another recession far worse than what we experienced in 2008.

Of course, this pending crisis is completely manufactured and entirely avoidable.

The bearer of Good News, the one who carries the message of Resurrection, is not motivated by fear of punishment (either for herself or others) but by confidence in her experience of the love of God. She knows God's love is greater than anything in herself or in her hearers; that Jesus can conquer anything in them that is not controlled by holy love.

"Such love has no fear, because perfect love expels all fear. If we are afraid, it is for fear of punishment, and this shows that we have not fully experienced his perfect love." 1 John 4:18

God's love has the final word, for Jesus has conquered the sin of the whole world and has defeated the grave. Christ's best messengers know this love by its all-consuming redemptive activity in themselves and confidently carry this love to others, without fear.

Two things are clear in both creation stories: 1) both men and women are created to exercise equal dominion, and 2) according to Genesis 1:31, this relationship between men and women was “very good.” This is what right relationship between men and women looks like. It is only after the fall of humanity — when we decided not to trust God’s ways, when we decided to grab at our own way to peace and gratification — that women were subjected to men. And I see nothing in the text that says this is the way God wanted it. Rather, I see this is the natural result of choosing to exercise a human kind of dominion rather than one that reflects the image of God. Humanity grabs at its own peace at the expense of the peace of all.

Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from Fred Bahnson's new book Soil and Sacrament: A Spirtual Memoir of Food and Faith.

The garden is our oldest metaphor. In Genesis God creates the first Adam from the adamah, and tells him to “till and keep” it, the fertile soil on which all life depends. Human from humus. That’s our first etymological clue as to the inextricable bond we share with the soil. Our ecological problems are a result of having forgotten who we are—soil people, inspired by the breath of God. “Earth’s hallowed mould,” as Milton referred to Adam in Paradise Lost. Or in Saint Augustine’s phrase, terra animata—animated earth.

The command to care for soil is our first divinely appointed vocation, yet in our zeal to produce cheap, abundant food we have shunned it; we have tilled the adamah but we have not kept it.

In his letter to the Romans, the apostle Paul writes: “I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God …” (Romans 8:18-19)

And who are God’s children in the immediate context? Paul explains the “children of God” are those whose spirits cry “father” when referring to God. “For,” according to Paul, “all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God.” (Romans 8:14) If this is true, then why is creation longing for the children of God (those led by God’s Spirit) to be revealed?

In Genesis 1, the author writes, “God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good.” The Hebrew words for “very good” are mehode tobe. Mehode means “forcefully” and in the Hebrew context tobedoes not necessarily refer to the object itself. Rather it refers to the ties between things. So, when God looked around at the end of the sixth day and said, “This is very good,” God was saying the relationships between all parts of creation were “forcefully good.” The relationship between humanity and God, men and women, within families, between us and the systems that govern us, and the relationship between humanity and the rest of creation — the land, the sea, and sky and all the animals and vegetation God created to dwell in those domains—all of these relationships were forcefully good!

It's no secret that most of us find ourselves longing for chances to vacate our normal scenery and the bustle of our everyday activities. It is, of course, a luxury and blessing of the modern world — and definitely of our country — that many of us have expendable income and time, but the ability and desire to take a break is something most of us would say that we need on occasion.

I think there is a biblical tie-in here as well. One of the spiritual revelations during my seminary years was one professor's focus on the “eighth day.” You are familiar, I am sure with Genesis' seven-day creation narrative. God created the heavens, the earth, animals, and mankind in six days. Then on the seventh day, God rested. This Divine day of rest then became the basis for God's gift of the Sabbath. It was a law (or was it Gospel?) given to God’s people in the book of Exodus, commanding that they break from work on the seventh day of the week — traditionally Saturday for the Jewish people. This day of rest was given so the people could find peace in not working, but also peace in God's presence. For the Jewish nation just released from slavery in Egypt, this day revealed a stark contrast from their lives as slaves — they now lived their lives as a chosen people of God.

This Sabbath tradition continued through the Old Testament and was even adopted by other cultures. But in spite of this gift, God's people never found true peace. Trouble continued, wars waged, life was still not perfect. Then, in the New Testament something happens. The Gospels each build up to, and point us toward, the cross. We see the seven-day passion narrative unfold beginning with the triumphal entry, climaxing in the cross, and then, following the historic tradition, Saturday becoming a day of rest as Christ is in the tomb.

But something changes.