Creation Care

As climate change devastates communities in Kenya, church leaders are helping to address the crisis locally while also calling on industrialized nations to own up to their responsibilities for spewing greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere.

“But we (in Africa) also have a role to play because we have not been very good stewards of the environment,” added Gichira, a poverty and development expert.“I think they (industrialized nations) are responsible for most of the emissions,” said Peter Solomon Gichira, the climate change program officer at the All Africa Conference of Churches. “They have responsibility to support climate change adaptation and mitigation as a moral obligation.”

People living in the Global South such as Kenya are suffering the worst consequences, climate experts say.

Droughts have become more severe and recurrent and are frequently followed by excessive rains or floods. Temperatures are much higher and weather patterns are now unpredictable.

I GREW UP IN RURAL IRELAND in the 1950s in a world surrounded by trees.

Close to my home, a ribbon of horse chestnuts lined both sides of the road. Each summer their intertwining canopies shut out the light, which gave the road its name—the dark road. In the fields around our house there were stands of oak, birch, elm, and sycamore. About 40 yards to the south and west, my father planted a shelter belt of Leylandii. We had different varieties of apple trees in the orchard, and two pear trees.

In 1962, just as the Second Vatican Council was beginning, I entered St. Columban’s seminary to be a priest. The seminary was located on a large estate called Dowdstown in County Meath. More than 150 acres were covered in woodlands full of indigenous trees such as oak, hazel, holly, ash, Scotch pine, willow, elm, and rowan. There were also exotic species, including a number of the sturdy cedars of Lebanon, a variety of cherry trees, and even a few California redwoods. The folklore in the area was that the trees had been planted in the 1820s by Gen. Robert Taylor, who had fought alongside Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo.

Trees are the dominant life form on land—and the longest-lived creatures on earth. During my seven years in seminary, while studying philosophy, theology, spirituality, and scripture, we never once looked to the natural world or trees for insight into our relationship with God, other human beings, or other species. And there is so much to learn! Sadly, theology and scripture presentations were isolated almost exclusively to the divine-human relationship, with little consideration given to the rest of creation.

Every year on Oct. 4 a strange thing happens outside of an ecumenical list of churches around the globe. As if each church were reenacting Noah’s Ark, a bevy of animals and their human counterparts congregate just outside the doors for a ceremonial Blessing of the Animals to commemorate the feast day of Francis of Assisi. The sight of horses, dogs, cats, birds, snakes, and pot-bellied pigs jockeying for position could be called disarmingly odd to a first timer or refreshingly quaint to the already initiated. As a follower of St. Francis myself, I would label the spectacle as revolutionary in a small way that continues to subtly permeate Christian culture to this day. Rather than celebrate the quirkiness of the ritual itself, I would like to speak to St. Francis as an icon for justice whose way of organizing and advocacy is not only rooted in Christianity, but may just provide the necessary strategy for handling a major justice issue of our time: Do all God’s creatures have a place in God’s house?

From the day Christ spoke through a cross at San Damiano Church, “Francis, go repair my household, which you see has fallen into ruin,” Francis of Assisi was called to restore God’s household. This call echoes the prophet Isaiah who called young people to restorative justice as “repairers of the breach and restorers of ruined dwellings” (Is 58:12). Scripture tells us that God’s household has many dwelling places (John 14:2): our worship spaces are contained in houses (Rom 16:5), our bodies are temples of God (1 Cor 6:19), even the Earth itself is a house within God’s household (2 Cor 5:1). The revolutionary thing that Francis appreciated about God’s household was the significance of the incarnation: Everything came to be through the Word of God (John 1:10) and the Word itself became Jesus Christ. By virtue of Creation, everything is related to Christ and a mirror to God.

Dare to go there with me, if you will. What if we imagine God’s vineyard as described in Matthew 21 to be this beautiful world we inhabit? What will happen if we reject it—if we continue to treat it with disrespect, fail to listen to its natural woes, dismiss the warning signs it gives us? What if God is keeping score? Oh. Dear. Might I remind us all, that if we do not tend to this earth, we are only inevitably hurting ourselves and the lives of future generations?

This is why, like never before, over one thousand groups and individuals, including various faith groups, businesses, peace activists, social justice groups, schools, and environmentalists from all over the country united for the largest climate march in history on Sunday, September 21, gaining international attention. The People’s Climate March, held in New York City, was the perfect moment to take a stand, create a buzz, and create the much-needed public influence and pressure as NYC prepared to welcome decision-makers from across the globe to discuss this very topic.

We all know that the world is moving down a very dangerous path, and that we must reverse our direction. But so far, the credible and persuasive scientific case hasn’t accomplished that. Sensible economic proposals haven’t halted that direction either. And smart political arguments have yet to reverse our course either.

Why? Because we are addicted to fossil fuels. The results are planet-threatening climate change and people-threatening terrorism.

We need conversion. Nothing less. Only our conversion could change our dangerous direction.

Two fundamental things could bring the kind of conversion we need.

One, our faith.

Two, our children.

More important than the celebrities or politicians marching on Sunday, members of the faith community came out in droves to support the rally. The Huffington Post reported on the wide variety of faiths that were represented at the march. A reporter from Christianity Today wrote, “Almost every conceivable strand of society was represented in the huge column of humanity — not only were there groups of Methodists and Baptists rubbing shoulders with Catholics and Presbyterians, there were Christians marching with Muslims, Jews, pagans, atheists and Baha'i. Anti-capitalist protesters stood alongside 'Concerned Moms for the Climate;' doctors, firemen, and vegans held banners next to indigenous people and victims of Hurricane Katrina.”

The reasons that thousands of individuals came out to the streets of New York City on Sunday are vast and personal. But for many members of the faith community, spreading awareness about the decaying state of God’s creation was a moral obligation. Signs such as “Jesus Would Drive a Prius” and a life-size moving Arkrepresented the importance of taking care of God’s creation throughout the rally. In a recent interview with the National Catholic Reporter, Steffano Montano, a theology professor at Barry University in Miami, said as a Catholic, there's a spiritual responsibility to combat climate change.

"By understanding creation, we can come closer to the Creator. It's an added spiritual responsibility. Justice for the earth is something that affects everybody. It's going to affect my daughter, my grandkids. It affects the poor in ways we are still trying to come to terms with. And it's our fault. So that's why we're here. It's on us to make a difference," said Montano.

What an amazing weekend! Barbara, Peter, and I had the privilege of hosting more than forty students from Christian colleges who traveled to New York for the People’s Climate March. On Sunday, we joined with other Christians for a morning prayer service in Central Park, and then squeezed in with an estimated 311,000 people for what is hands-down the biggest climate demonstration ever.

We had our choice of groupings on the march. Leading the way were those already affected by climate disruption, followed by students, youth, and elders. Fifteen blocks back stood those working for solutions, such as renewable energy and environmental justice advocates. Another ten blocks and the scientists and faith groups stood shoulder-to-shoulder. And in the rear was an assortment of cities, states and countries from virtually everywhere.

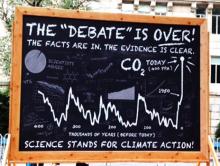

We chose the Science and Faith section. There we were, beneath an enormous blackboard prepared by scientists declaring “The ‘Debate’ is Over!”

Its chalk markings depicted the trends in atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the last 400,000 years, with the unprecedented and terrifying spike in the last half-century; a pie-chart of the 97 percent of climate scientists who agree on the consensus science of manmade global warming; a line graph showing the precipitous decline in Arctic sea ice cover; and the Keeling Curve demonstrating the inexorable growth in greenhouse gases every single year. Around us stood technicians in white lab coats, research scientists of every stripe, Christian college students, university professors, grandmothers demanding climate action, and young parents pushing strollers—including our own kids, Lindsey and Brad, with our beautiful granddaughters.

The debate is over. Right?

On Sunday, Noah's Ark will be rolling through the streets of New York City.

Powered by a bio-diesel truck and paid for by faith-rooted climate activists, it will drive on Manhattan’s West Side alongside hundreds of thousands of climate activists calling for climate justice.

The ark appeared in a collective dream with other faith-rooted activists and organizers about how our wisdom traditions could speak to this urgent moment with radical creativity and dramatic flair.

The same old calls for action aren’t getting through. We don’t have much time to act, yet our world leaders lurch from crisis to crisis while the frog slowly boils in the pot. We are living through one of the greatest extinction in our planet’s history. And even if we did survive the Earth’s death by some technological miracle, what kind of life would that be?

We must help people see that climate disruption is real and that there are solutions. We need to help the media and our political leaders see this movement as truly multiracial, multigenerational, multifaith, and of many economic backgrounds.

Reuters reported today that UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon is starting his drum beat to gets heads of state to his emergency climate conference in New York at the end of the month.

“Ban wants heads of state at a Sept. 23 gathering in New York to outline how their countries will contribute to a mutual goal to contain rising temperatures," said Selwin Hart, the Barbadian diplomat helping to spearhead the conference. The final deal is due to be signed in Paris in 2015, according to Reuters.

This one-day, “leaders-only” Climate Summit is somewhat unprecedented. U.N. climate negotiation meetings are usually called by the executive secretary of the UN’s climate caucus (UNFCCC) and attended by directors of environmental agencies. Ki-moon is switching things up because, as we’ve learned, effective policy to reverse global warming is about economics, not science or technology.

“You don’t control economic policy at national level if you’re an environment minister,” said Michael Jacobs, a former climate change advisor to the U.K. government.

Here in Kabul, one of my finest friends is Zekerullah, who has gone back to school in the eighth grade although he is an 18-year old young man who has already had to learn far too many of life’s harsh lessons.

Years ago and miles from here, when he was a child in the province of Bamiyan, and before he ran away from school, Zekerullah led a double life, earning income for his family each night as a construction crew laborer, and then attempting to attend school in the daytime. In between these tasks, the need to provide his family with fuel would sometimes drive him on six-hour treks up the mountainside, leading a donkey on which to load bags of scrub brush and twigs for the trip back down. His greatest childhood fear was of that donkey taking one disastrous wrong step with its load on the difficult mountainside.

And then, after reaching home weary and sleep deprived and with no chance of doing homework, he would, at times, go to school without having done his homework, knowing that he would certainly be beaten. When he was in seventh grade, his teacher punished him by adding 10 more blows each day he came to school without his homework, so that eventually he was hit 60 times in one day. Dreading the next day when the number would rise to 70, he ran away from that school and never returned.

Now Zekerullah is enrolled in another school, this time in Kabul, where teachers still beat the students. But Zekerullah can now claim to have learned much more, in some cases, than his teachers.

The reality of climate change can be tough information to absorb, and if you’ve known for a while, it can just plain get you down. Yes, rising carbon pollution is leading to global warming. The impacts are already happening now, especially in poor countries and on our coasts. So now what? In the face of a problem on a global scale, what are we to do? Here are four suggestions.

1. Pray.

The massive scale of global warming is a reminder that we are only human. It’s overwhelming to think about and difficult to know where to start. The good news is, God is waiting for us to hand over all our burdens. This is God’s world, not ours – a perspective that can inform not only our outrage over what humans have done to the creation, but also our response. We can be the hands and feet of Christ, doing the work God calls us to do, but we are not the saviors of the world. Knowing that can be both humbling and strengthening. Prayer is a great place to start if you’re trying to figure out what to do about climate change, and it’s an equally important place to return to if you’ve been fighting the good fight for years (exhaustion and burnout are a real thing in this line of work!).

The deep, dark secret of the church is that the beliefs and convictions of Christians are often shaped far more by the hymns we sing than the theological tomes gathering dust on our bookshelves. Songs are avenues for praising God, but they are also tools for imparting knowledge. Singing is a theological exercise, so the words printed in hymnbooks or flashed on screens deserve attention and reflection.

“How Great Thou Art” has been sung in churches, automobiles, and probably the occasional shower since the late 19th century. Long used in traditional worship services, many contemporary artists are offering their own renditions of this classic and adapting it for more contemporary settings. Even Carrie Underwood (no relation) is getting into the act.

This is an ode to God’s majesty and power. It testifies to the beauty created by God’s hand and witnesses to the connection between the love behind God’s creative acts and the love poured out by Christ on the cross.

The famous opening line, “O Lord my God, When I in awesome wonder, Consider all the worlds Thy Hands have made” sets the stage. They also easily get stuck in your head playing on endless loop.

Creation – stars, thunder, forest, birds, majestic mountains, gentle breezes, and everything else – indicates the greatness of God. It provokes wonder among us humans, forcing us to acknowledge the subordinate relationship between creature and Creator. We cannot do what God has done; our accomplishments will always pale in comparison.