Abolitionists

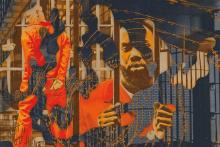

AMERICAN HYPERPOLICING and mass incarceration are products of 50 years of cynical politics, vicious economics, and unconscionable racism—as the mass uprising in the wake of George Floyd’s killing has brought into ever clearer focus. Across the country, organizers on the ground are pushing to defund the police. Meanwhile, for people Left, Right, and center, “ending mass incarceration” has become a standard political talking point. But what precisely would “ending mass incarceration” entail?

Imagine that tomorrow we were to enact the most radical reforms to the prison system conceivable—reforms tailored to mass incarceration’s political, economic, and racial dimensions. First, to scale down the war on drugs, we could pardon every person in state and federal custody who is incarcerated solely on the basis of a nonviolent drug offense. Second, to stop caging people simply because they are poor, we could release every pretrial defendant who is sitting in jail solely because they are unable to make bail. Third, to end what’s been called the New Jim Crow, imagine if every Black state and federal prisoner—who constitute one-third of those in prison—were freed, regardless of whether they were guilty of a crime. By committing to these three measures (which, needless to say, aren’t being seriously considered in Washington or in any state capital), the U.S. would reduce its prison population by more than 50 percent, to a tick over 1 million people. In the COVID-era especially, when prisons and jails are incubators of the virus, many lives would be saved. Families would be reunited. Much suffering would be forestalled.

What such a robust menu of reforms would not meaningfully do, however, is end mass incarceration. Even at half its current size, the U.S. incarceration rate would remain three times that of France, four times that of Germany, and similar degrees in excess of where it was for the first three-quarters of the 20th century. Given the massiveness of the American carceral edifice, we cannot reform our way out of mass incarceration. Nor does the reformist impulse address the crux of the problem.

In her sermon on the last Sunday of Black History Month, the Rev. Maria Swearingen preached about her belief that black lives, “queer lives,” and immigrant lives matter.

And since it also was Transfiguration Sunday, she pointed to the story in the Gospel of Matthew where God declared Jesus “beloved.” That is a term, she said, that can be used for everyone.

I can remember hearing several times as a middle and high schooler that Christians lie the most when they sing. These claims generally came from the mouths of college-aged worship leaders during emotional praise segments at mission camps and conferences. They were usually followed up with a heartfelt plea to raise honest words and promises to God during the next song. (And if we really meant it, we would ignore the burning stares of our judgmental, worldly peers and come down front for our seventh altar call.)

Though I generally don’t remember these scenes and indictments fondly, I have recently been contemplating the idea of honest worship, especially in relation to the Christmas season. I mean, how often do we memorize a whole song and sing along to it regularly without really stopping to contemplate the lyrics? And even when we do realize what we’re singing, how often do we actually let those words transform our hearts or actions or perspectives?

All of these thoughts started stewing in my mind during my Thanksgiving vacation two weeks ago. Per usual, I started playing Christmas music the day after Thanksgiving (and by the day after I mean a few days before). As I was washing dishes, belting out my favorite version of “O! Holy Night,” I was suddenly struck with the thought What am I singing? Read the lyrics below to see if you get what I mean. (Hint: my moment happened somewhere around the second verse.)

They say at some point in their lives great leaders experience a "dark night of the soul," or a period in life when your feet, knees, and face scrape and stick to the proverbial bottom." It is a time when even your soul feels forsaken. Ultimately, the dark night is not about the suffering that is inflicted from outside oneself, even though that could trigger it. It is about the existential suffering rooted from within. St. John of the Cross, the 16th century Carmelite priest, described it as a confrontation, or a healing and process of purification of what lies within on the journey toward union with God.

"Whenever you face trials of any kind," explained the apostle James, "consider it nothing but joy, because you know that the testing of your faith produces endurance; and let endurance have its full effect, so that you may be mature and complete, lacking in nothing." (James 1:2-4)

Yesterday, I posted a blog about how to get beyond labels when engaging in discourse with another individual. Today I'd like to share some tips on how to get beyond labels and have civil discourse with a group.

Certain moments in our nation's history have consistently opened the door for the least civil voices to enact evil through civil policy: think the institution of race-based U.S. slavery, the Indian removals, Jim Crow laws, legalized segregation, the federal protection of lynching mobs, and, don't forget, the Japanese internment camps, among others.

Some years ago on a trip to the U.K., I walked through the historic Holy Trinity Church on Clapham Common in South London.

Through faith and business savvy, the Hagar Project gives new life to freed slaves in Cambodia.

The 18th and 19th century movement to abolish slavery, with its many Christian leaders, has much to teach us.

Dr. Samuel Cotton, a pioneer of the modern anti-slavery movement, died in December after a protracted battle with cancer.