Articles about giving thanks, while keeping in mind past—and current—injustices that concentrate abundance in the hands of too few.

Thanksgiving. That word holds profound meaning for Americans, most of it nostalgic. I remember in grade school when our classes would present Thanksgiving pageants that retold the story of Thanksgiving. We all know it by rote:

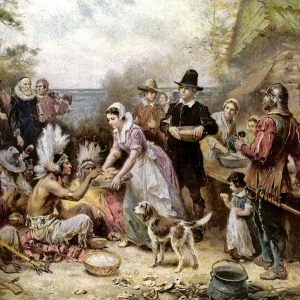

The pilgrims were persecuted in England (probably because the men wore buckles on their hats, culottes, and white stockings — who does that?). Anyway, in 1620, they got in a boat and sailed to America, where they met brown people in paper cutout, feathered headdresses and hand-me-down 1970s fringe vests and wrangler jeans. The pilgrims said “Hi!” and the headdress people (called “Indians,” for no good reason) said “How!” When the pilgrims realized they didn’t know how to cook the food in this “new world,” the Indians showed them how to cook cornbread, cranberry sauce, and collard greens (or at least that’s how the story went in my school). Turkeys were plentiful in the new world, so when the hat buckle people and the headdress people held a feast in November of 1621 to celebrate their new friendship, a turkey sat at the center of the table.

Gratitude reminds us that a better world is possible.

WE HEAR A lot about gratitude as both spiritual practice and a boost to our mental health. But I confess: Lately I’ve caught myself asking what, exactly, is there to be so thankful for?

In the U.S., Thanksgiving is upon us. We are expected to be thankful and celebratory. In the face of so many national and global crises, however, feeling gratitude can be challenging. Authoritarianism and political violence are rising in the United States. Preventable suffering and death around the world are surging due to ongoing war in Ukraine, the Middle East, Sudan, and beyond and the Trump administration’s dismantling of foreign assistance programs for health and food security.

Many of these prayers grapple with what it means to give thanks for God’s abundance in a world that fails to share that abundance equally, on a holiday that is a painful reminder of how poorly European Christian settlers repaid Indigenous hospitality.

I’m not suggesting we not be thankful. But if it were up to me, I’d repeal the official day of Thanksgiving that was sanctioned by Congress because no matter how we want to re-tell or re-write that story, we are marking an event of injustice.

In removing this day, I’d encourage the whole country to express sorrow for such a grave injustice to the Native Indians and create events and various forms of curriculum in parallel. I’d express gratitude and celebration of the story and legacy of the native Indian people. And I’d put into law that ensures reparation for every single descendant of Native Indians. Furthermore, I’d create a fund to guarantee 100% funding to college for any descendants of Native Indians. This is just for starters….

In my opinion, our treatment of the Native Indians is one of the greatest human tragedies and to ignore its story and context may be the pinnacle of historical revisionism.

An Interview with 'Grateful' Author Diana Butler Bass

Woodiwiss: We're coming up on Good Friday and Easter. And a lot of strains of Christianity teach the story of Good Friday as, “God also gave us this gift of Jesus’ death. It was horrible, but Jesus did it to pay for our sins, so we have to worship him.” There's this implied debt.

Bass: It makes absolutely no theological moral or biblical sense at all. So where do we get that? It's very complicated, but Protestantism was built on this idea of faith: On one hand, they said that salvation was a free gift, that it was the act of grace. On the other hand, they complicated that free gift with this idea of economic exchange.

When we think about the meeting of the first pilgrims and the Native Americans, we usually connect vicariously to one side of that old Plymouth encounter, mysteriously linking our faith journey to the early pilgrims’ faith journey. But what about those long-ago Native Americans? Is there a reason to remember them as more than a foil for the pilgrims?

Year after year we think warmly of that first union of the pilgrims and the Native Americans — and then we continue on in the supposed faith tradition of one of those peoples without another thought to the fate of the others.

So what role do those old Native Americans play in our faith today, and how might we bring them to mind or honor them? Here are a few ways you can faithfully honor both sides of the Thanksgiving table this year.

Genuine gratitude brings us humility and reconnects us with God and each other —especially those who need us in some way. It erases our society’s illusions about winners and losers. It directly challenges our judgments about who is deserving and who is undeserving. It reminds us of our total dependence on God for everything.

Sometimes we don’t know what to pray,

or how to talk to you about fixing what’s broken.

We pray in generalities, that you’ll

“be with us, guide us, restore us”

but sometimes, that’s not the tangible need

we really want to name.

IMAGINE AN UNLIKELY DUET. One singer is National Review senior editor Jonah Goldberg, a conservative political columnist who admits he indulged in “smash-mouth” rhetoric and once did a video mocking “social justice” as meaningless mush. The other is religion scholar Diana Butler Bass, a progressive liberal and author who champions social justice as central to a life of faith. Both published books this spring, and as they made separate media rounds, they sang the same song—an ode to gratitude.

Gratitude is having a big turn in the spotlight right now as influential writers, university researchers bolstered with millions in foundation grant funds, #blessed social media mavens, and more tout thankfulness as a boon to one’s spirit and health.

In my research and experience as a teacher educator, I have found social studies curricular materials (textbooks and state standards) routinely place indigenous peoples in a troubling narrative that promotes “Manifest Destiny” – the belief that the creation of the United States and the dominance of white American culture were destined and that the costs to others, especially to indigenous peoples, were justified.