Oct 11, 2019

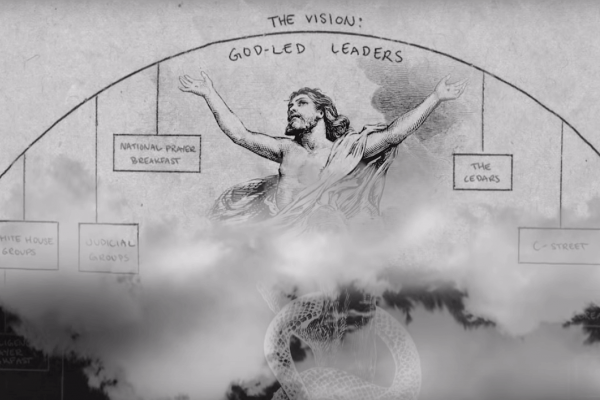

The message we’re sending to people in power is possibly not the Gospel message.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login

The message we’re sending to people in power is possibly not the Gospel message.