WHEN I WAS IN COLLEGE, I asked one of my faith leaders at the time why no women were in positions of authority in that ministry. He said that the male leaders’ wives were always available to serve as mentors. Besides, he added, if they hired a woman, she would just get married and quit to raise a family.

I left, I fumed, and then I read Sarah Bessey’s Jesus Feminist, which told me that not only could women serve as pastors and leaders in the church, but that Jesus wanted them to.

If that were so, I wondered, why had I encountered so few female faith leaders?

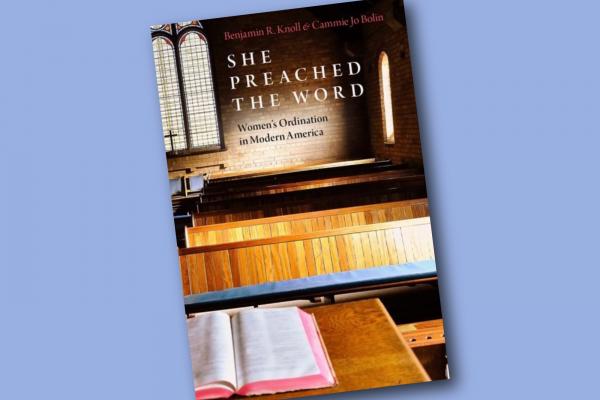

Benjamin R. Knoll and Cammie Jo Bolin have provided an answer. In She Preached the Word: Women’s Ordination in Modern America, Knoll and Bolin examine why women still make up just 15 percent of congregational clergy.

Read the Full Article