Culture Watch

Old New Soul

Leon Bridges is a 25-year-old gospel and soul singer from Texas with a vintage sound and sheepish stage presence. In six months, Bridges went from washing dishes full-time to selling out multiple SXSW shows. His new album, Coming Home, features smooth love songs, both romantic and religious. Columbia

JEFF SHARLET, author of nonfiction books about faith including New York Times best-seller The Family and Sweet Heaven When I Die, isn’t so much interested in religion as he is in belief. “That interest sometimes leads me to people who might reject the term religion altogether,” he writes of drinking whiskey with Mormons and marching in Spain with Jewish-American veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a volunteer group of up to 40,000 men and women from 52 countries who traveled to fight fascism in the Spanish Civil War.

In his newest book, Radiant Truths, Sharlet collects stories like these, stories about what happens when religious ideas meet social practice. He attributes this concept to anthropologist Angela Zito. In her essay “Religion is Media,” Zito ponders, “What does the term ‘religion,’ when actually used by people, out loud, authorizein the production of social life?” Using Zito’s question as a jumping off point, Sharlet dives into 150 years’ worth of literary journalism at the intersection of religion, culture, and politics.

I’M IN THAT cohort of earnest, educated, now-middle-aged North Americans who fell in love with Dave Eggers’ sprawling, sometimes unapologetically self-indulgent memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. All my life I had lived with an ongoing inner monologue of exaggerated self-consciousness, but I’d never read anyone who could articulate the experience as precisely, never mind playfully, as Eggers.

Eggers could have made a fortune repeating the same entertaining self-indulgence, but he’s shaped his career into anything but navel-gazing. He’s formed writing workshops for kids; started two long-running magazines; cofounded an oral history book series on human rights crises; and written a string of beautiful, compassionate books of fiction and nonfiction with an unmistakably critical eye.

In his latest novel—Your Fathers, Where Are They? And The Prophets, Do They Live Forever?—Eggers uses a dialogue-only form to tell a compact story that thunders with probity and timeless, existential urgency. The main character, Thomas, a middle-aged man with psychological issues, has conversations with six different kidnap victims—an astronaut, a former member of Congress and Vietnam vet, his high-school teacher, his mother, a policeman, and a woman he meets during walks on the beach—holding them on an abandoned military base on the California coast. He doesn’t physically harm any of them; he just wants to know where everything went wrong. Why do our friends die? Why do our career dreams come to naught? Why do the mythical promises of science, democracy, education, nationalism, law, progress, and even love fail to deliver?

CHRIS HOKE’S Wanted isn’t a spiritual memoir in the sense of chronicling revelation over time, and while Hoke, as his own character, grows through the book, he isn’t tracking the movements of his own soul. Wanted recounts the moments in Hoke’s life as a pastor and friend to prisoners, migrant workers, and gang members when something else broke in. Whether or not it intends to, Wanted is a way of answering the question that plagues a lot of contemporary spiritual writing: What does spiritual mean, anyway? Outside the religious patterns we already know, how would we recognize it?

Hoke goes looking, and finds himself drawn to a jail in Washington’s Skagit Valley as an unofficial chaplain, leading Bible studies and hanging out with the men who soon request his visits. Many of them listen to the stories where Jesus dines with the people society rejected and ask if that could mean them too.

AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON asks what happens when you give a computer the ability to think for itself. To which we could add, what happens when you make a science fiction film that assumes the audience can think for itself?

Sadly, in the case of Age of Ultron, writer-director Joss Whedon’s serious attempt to make a smart blockbuster collides with corporate cookie-cutting and the belief that stockings are best overstuffed, even if what’s in them is just cotton wool or dead weight. Too much is going on, and not all of it is good. Thor, the Hulk, Iron Man, Black Widow, and the other guy with the arrows are still looking for a magical object, but when they find it we’re none the wiser about what it’s for. Bad guys still threaten the safety of the world, and the Avengers still think that only maximum force can secure a result.

THE CLUB WAS full by the time New Jersey’s The Gaslight Anthem took the stage. Lead singer and songwriter Brian Fallon stepped to the mike in denim jacket and jeans, and the band lit into their song “Howl” (yes, a Ginsberg reference). That’s when I heard a strange doubling sound on Fallon’s vocal. The Gaslight Anthem is very much straight-ahead, meat-and-potatoes, guitars-and-drums. Why would they use that weird effect on the vocal?

Then it hit me. That sound wasn’t coming from the sound board or the speakers, but from us. The audience, en masse, was singing along with every word, on time and in tune. It was what happens when rock and roll is working right: The performers and the audience become one and are swept up into something much larger than themselves.

THE DEVIL HAS long been wildly popular on stage, dating back to the Middle Ages when church authorities routinely cancelled performances because they worried that representations of the devil were so deliciously tempting that weak believers might falter. The dualistic image of a good, sweet angel on one shoulder and dirty demon on the other has infiltrated popular culture from children’s cartoons to adult sitcoms, signifying the struggle of our tempted conscience. And the devil always has the better jokes. In literary works, such as Paradise Lost and Doctor Faustus, the devil’s presence has driven plots forward through acts of temptation, leading the protagonist into some lusty or murderous act. The cliché is brought to life: “The devil made me do it.”

In 2015, the devil makes a serious comeback on Broadway in a successful run of Robert Askins’ new play, Hand to God, nominated for five Tony Awards, including best play and best direction. Askins takes his audience on a different kind of devilish journey.

AT THE WORLD Christian Gathering of Indigenous People in 1996, our North American Native delegation was unable to find any “Christian” Native powwow music that we could use to dance to as part of our entrance into the auditorium. This was important at the time, as we didn’t feel the liberty to use “non-Christian” powwow music for a distinctly Christian event. A contemporary Christian song by a Caucasian worship leader using some Native words and a good beat was selected.

Except in a handful of cases (believers among the Kiowa, Seminole, Comanche, Dakota, Creek, and Crow tribes, to name some)—and those always in a local tribal context—Native believers were not allowed or encouraged to write new praise or worship music in their own languages utilizing their own tribal instruments, style, and arrangements.

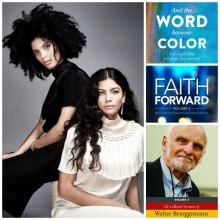

Contemporary History

The duo Ibeyi are Naomi and Lisa-Kaindé Díaz, 19-year-old French-Cuban twins with Yoruba roots—a West African culture transplanted to Cuba during slavery. Ibeyi’s self-titled album begins and ends in prayer; in between is a fusion of English and Yoruba, minimalist piano and percussion, jazz and hip hop. XL Recordings

WITH A LONG history of involvement in the evolution of the Social Security program, Nancy Altman and Eric Kingson are the right analysts to explain the program and demonstrate conclusively that, with careful tending by Congress, Social Security will be there for future generations: a critical part of retirement finances for the vast majority of the American people and, for many, the only retirement support. They argue that Congress should be strengthening and expanding Social Security—and they show how this can be done and the bill paid.

The book makes clear that Social Security is not an entitlement program but a social insurance program with premiums paid through payroll taxes. Its $2.8 trillion trust fund represents the full-faith support of the American people to provide essential insurance coverage for all our people against the universal hazards of death, disability, and old age. It compares how our system stacks up against those of other advanced industrial societies. (We are distinctly less generous to our senior citizens than other developed nations.)

REBECCA TODD PETERS offers here a concise treatment of the major moral concern of a large part of Christian social ethics: the structures of globalized economic life and their manifest injustices and unsustainability. She also offers a moral framework to guide the thinking of unjustly, and often blindly, privileged First World Christians about the moral situation in which we find ourselves.

She proposes concrete action guides for how such First World Christians can gradually and intentionally empty ourselves of these privileges in order to stand in solidarity with those whose lives are harmed in the delivery of our advantages. In the end what emerges is a kind of liberation ethics for those who didn’t know they needed to be liberated—in this case, from their own advantages.

BIBLICAL LAMENT includes both pleas to God for help and mournful dirges. Sometimes they are rooted in individual travails and grief, other times in anguish for those crushed by injustice or war.

The psalmist and the prophets dig deep into visceral images of bodily suffering—and stretch up, out, yearning to find symbols and metaphors in nature that might capture the mercy and presence of a God who, the psalmist isn’t afraid to say, is sometimes a bit elusive.

EARLIER THIS year came a flurry of new horror stories about the abuses of human dignity that are, apparently, common in many of America’s college fraternities. First came the video from the University of Oklahoma in which a busload of “true gentlemen” of Sigma Alpha Epsilon are seen and heard spewing racist bile. Shortly thereafter the revelation that the Kappa Delta Rho chapter at Penn State had maintained a private Facebook page featuring nude photos of unconscious young women became national news.

The old saying “Once a frat boy, never a man” may be just another sweeping stereotype. But the evidence is mounting that many of the nation’s fraternity houses are the breeding ground for an exclusive culture of entitlement and impunity that their mostly white, upper-class members carry into their future roles in the elite circles of business and government.

It should be noted that when we talk about “fraternities,” we are really just talking about the historically all-white social organizations with Greek-letter names. Historically black fraternities have their own problems, especially with hazing, but they have experienced nothing like the epic bad behavior found among their paler brethren.

IT’S THE 50TH anniversary of The Sound of Music. I never thought I’d write about it here, but someone recently offered me the kind of gentle admonishment that Maria might have given to the von Trapp children. Maria is usually right, and my friend is too. One of the wisest film critics I know, a man dedicated to contemplation and activism and who doesn’t shy away from the more challenging edges of cinema, still considers it his favorite film.

THE EXTRAORDINARY film Leviathan takes place in a tiny coastal town on the other side of the world, but it relates to all our dreams and fears.

A man is tormented by bureaucracy, as the authorities try to take his house. He has an unhealthy relationship with alcohol, and a very unhealthy one with his partner. He works on people’s cars, does favors for people who ask him, and tries to raise his son as best he can. And he’s caught between the wheels of historic oppression and emerging forms.

Leviathan, this year’s Russian nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, is a work of uncommon cinematic bravery, for the people who made it take on the corruption of their current political masters. Vladimir Putin appears briefly, as a portrait looming over the office of the mayor trying to take our hero’s house. But the graft, selfishness, and cruelty of Putin’s imperial reign are palpably present in the mayor, who has been fighting the householder for years to get his property, for reasons that owe more than a little to the legacy of Soviet-era patriotic ideology. Communism has been replaced by a heady mix of nationalistic pride and elitism religion, whose boundaries are enforced with no mercy. Pussy Riot’s punk prayer gets a mention in a priest’s litany of things that are undermining Mother Russia. It’s the same old story, there and everywhere—keep the nation pure, confuse spirit and law, and wreck your own life by denying the glories of human diversity.

OUT WHERE Kentucky meets West Virginia, you’ll find one of America’s cultural seedbeds, where Scotch-Irish immigrant traditions took root in the New World. But on her debut album, American Middle Class, singer-songwriter Angaleena Presley, a daughter of the Kentucky mountains (and no kin to The King), paints a heartbreaking picture of what Appalachia has become.

The people of this region were once mostly self-sufficient subsistence farmers. In the early 20th century, they were drafted into the coal mines but brought their pride and independence with them, waging often-bloody battles to establish the United Mine Workers of America. For over a century now, the region’s economic fate has been hostage to the ups and downs of the energy market. As a result, the coal fields have become one of the poorest parts of the country.

The music that flourished in this region became, along with that of low-country African Americans, one of the two great pillars of American popular music. So many country music greats have come from here that Kentucky has a “Country Music Highway Museum” just to honor all the stars (Loretta Lynn, Ricky Skaggs, Billy Ray Cyrus, Keith Whitley, and many others) born along U.S. 23.

IN A RECENT interview, Wendell Berry reiterated how perplexed he was that many Christians who are guided by a deep love for God can participate so willingly in an economy that is rapidly devastating God’s creation. In his new book One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America, Princeton historian Kevin Kruse offers a narrative that sheds light on how our churches got into the mess that Berry bemoans. As the book’s subtitle indicates, the primary story that Kruse traces is that of the genesis of “Christian America,” which unfolded not in the era of the Founding Fathers, as David Barton and other conservative Christians contend, but rather in the mid-20th century with industrialists who rallied churches to oppose FDR’s New Deal.

“WE ARE AT the moment when our lives must be placed on the line if our nation is to survive its own folly.”

Martin Luther King Jr. gave this stinging critique of the apathetic nature of both the U.S. church and the general public more than 40 years ago. While some things have changed for the better, the truth remains that the three evils of society that King named (racism, militarism, materialism) continue to pervade U.S. culture, crippling our moral and ethical foundation.

It is difficult to imagine that someone the FBI once labeled as “the most dangerous man in America” would one day have his own national holiday. Each year we celebrate the life of King with an incomplete and romanticized retelling of the impact he had on society during and after the civil rights movement. He dreamed of a better nation, but what was it about his dream that made him a nightmare to the U.S. government?

Rosemarie Freeney Harding describes the reaction of her friend—Albany, Georgia-based civil rights leader Marion King—to a physical attack.

In the summer of 1962, in the middle of the Albany campaign, Marion and I were both pregnant. During the campaign, Marion often visited movement workers who were jailed in local facilities throughout Dougherty and Terrell counties—taking them food, checking on conditions where they were kept, relaying messages. On one occasion as she exited a jail, a policeman who felt she was not moving fast enough kicked her in the back so that she fell to the ground. Marion fell so hard that she lost the baby.

EARLY IN Being Mortal, surgeon Atul Gawande tells the story of Joseph Lazaroff, a patient with incurable prostate cancer. His medical team pursued multiple treatments, including emergency radiation and surgery, but Lazaroff ultimately died. What most struck Gawande later was that he and the team avoided talking honestly about Lazaroff’s choices—even when they knew he couldn’t be cured.

“We could never bring ourselves to discuss the larger truth about his condition or the ultimate limits of our capabilities, let alone what might matter most to him as he neared the end of his life,” Gawande writes. “The chances that he could return to anything like the life he had even a few weeks earlier were zero. But admitting this and helping him cope with it seemed beyond us.”

Why is that? For one, Gawande’s medical training didn’t prepare him for dealing with frailty, aging, or dying, he writes. He and his peers were taught to “fix,” to heal people with expertise, tools, and tests. Like most doctors, he approached his patients’ challenges as medical problems to solve, whether they were the accumulations of old age or terminal illness.