Culture Watch

A Good Neighbor

Children’s television host (and Presbyterian minister) Fred Rogers was known for his gentle, soft-spoken manner. Michael G. Long argues in Peaceful Neighbor: Discovering the Countercultural Mister Rogers that Rogers was also a radical, imbuing his show with nonviolence and care for creation. Westminster John Knox Press

I GREW UP terrified, my childhood catechized by the violence in Northern Ireland, each week a litany of murder. I grew used to the idea that killing was the story of our lives. This, of course, was not true—there was also beauty and friendship all around us, all the time, not to mention eventually a peace process that has delivered extraordinary cooperation between former sworn enemies.

But the way we learned to tell the story—from political and cultural leaders, religion, and the media—emphasized the darkness. It’s been a long and still ongoing journey for me to discern how to honor real suffering while overcoming the lie that things are getting worse.

Today, many of us are living with a fear that seems hard to shake. Horrifying, brutal videos, edited for maximum sinister impact, showing up in our newsfeeds are only the most recent example of how terror seems to blend into our everyday lives.

But things are not as bad as we think. What social scientists call the “availability heuristic” helps explain why we humans find it difficult to accurately predict probability. In short, we guess the likelihood of something happening based on how easily we can recall examples of something similar having happened before. Because of this, folk who get a lot of “information” from mainstream media may tend to overestimate the murder rate: Most of us have seen vastly more killing on TV than would ever compute to an accurate estimate of real-world rates of killing.

Going it Alone

CLINT EASTWOOD has made films about the sorrow and repeating pointlessness of war, as seen through the eyes of both aggressor and aggressed-against, with empathic performances and unbearably moving impact. His American Sniper, about the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, bloodied in Iraq and struggling at home, is not one of those films. At best it’s a valuable character study of a confused warrior, revealing the traumatic effect of his service. At worst it’s a jingoistic and xenophobic attempt to put varnish on a terrible national response to the horror of 9/11, a response that became a self-inflicted wound creating untold collateral damage.

A decade ago, Eastwood made Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, which saw World War II soldiers as propaganda fodder and had the moral imagination to show both sides as courageous and broken without denying the difference between attacker and defender. These films are respectful and thoughtful, but American Sniper is arguably a work born in vengeance. Its reception (becoming one of the biggest January box office weekends ever, and a quick right-wing favorite) is part of the failure to deal in an integrated way with the wounds of 9/11, or to even begin to face the reality of the war in Iraq: an imperial conquest using the cover of national trauma as a justification

THE BATTLE over net neutrality keeps getting stranger and stranger.

For years the lines were clearly drawn. On the “pro-” side were the content-providing companies (Google, Netflix, Amazon, etc.) and the public interest and consumer groups that want to preserve equal access to a potential audience of billions. Arrayed against them was Big Telecom (Verizon, Time Warner Cable, Comcast, etc.), which wanted the internet to work more like cable TV, where consumer choice is limited to the menu the provider offers.

But now the idea that internet service providers should be prohibited from charging content providers for faster downloads has become so popular that even its sworn enemies claim to favor it. They’ve even rounded up some of their most fervent supporters in Congress to push “net neutrality” legislation, which may come with a rider proclaiming that “war is peace.”

Comcast, the nation’s largest cable and broadband provider, pioneered this Orwellian strategy. For several months now Comcast has run print, TV, and online ads hailing its support for net neutrality—no “blocking” of sites, no “throttling” of download speeds, and no “paid prioritization” giving faster speeds to the highest bidder. Not only does Comcast support those principles, it says, but it is in fact the only internet service provider that has made a legally binding commitment to abide by them. And, by the way, if the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) would just approve Comcast’s merger with Time Warner Cable, it would extend those protections to all Time Warner customers, too.

WE LIVE IN an age of deep fragmentation. Like the ancient Gnostics, who believed in a deep divide between mind and body, we too are inclined to elevate the mind, or the spirit, over the body. The critic Harold Bloom once suggested that the religious practice of most Americans is “closer to ancient Gnostics than to early Christians.”

Ragan Sutterfield’s new memoir, This is My Body: From Obesity to Ironman, My Journey into the True Meaning of Flesh, Spirit, and Deeper Faith, recounts the story of his own struggles amid the fragmentation of our times. Having wrestled with being overweight since his childhood, Sutterfield eventually finds himself with a failing marriage and at his heaviest weight. He is faced with the incongruity that he is an environmentalist and farmer, doing grueling work to care for the land and creation, and yet taking poor care of his own body.

This is My Body is a compelling story of conversion, not unlike St. Augustine’s Confessions, as Sutterfield finds himself drawn out of the typical U.S. sort of Christianity that has little regard for the body and into a deeper faith in Christ, in which spirit and body are deeply interwoven. After the collapse of his first marriage, Sutterfield surrenders himself to the disciplines needed to care better for his body, specifically controlling his diet and becoming serious about exercise. From this conversion point onward, Sutterfield begins to learn and experience an incarnational faith in which our bodies cannot be taken for granted. He writes:

What if God ... became flesh and remains enfleshed? What if God not only has a heart that longs for our love but also a heart that pounds with blood? What if God has skin that drips with sweat? What if the God who offered his body as a sign of love also wants us to experience our bodies as a gift of ... love? Christians must worship a God who is all of these things because we worship a God who was made manifest to us in the human, embodied life of Jesus.

NOEL CASTELLANOS is the CEO of the Christian Community Development Association, a network of Christians committed to seeing people and communities restored spiritually, economically, physically, and mentally. In order to nurture that holistic work, committed CCDA practitioners move into under-resourced neighborhoods and try to foster community. Castellanos’ experience with CCDA and a lifetime of missional community has informed his new book, Where the Cross Meets the Street: What Happens to the Neighborhood When God Is at the Center (IVP Books), a powerful testament to the necessity of externally focused ministry. He was interviewed via email by Dave Baker, who is responsible for school accounts and diversity initiatives at Baker Book House.

Dave Baker: You write that in terms of diversity, the evangelical community is far behind the rest of society. In what ways?

Noel Castellanos: Most evangelical denominations and organizations are not very ethnically or culturally diverse in leadership. With the amazing demographic changes that are happening in our country, how can we possibly be in a position to effectively reach and disciple people of color if the leadership on boards and in executive positions is all white?

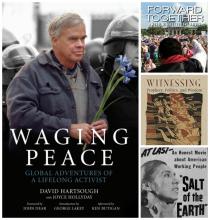

SOME PEOPLE (I was one) will initially read this book to learn what it was like for the author to grow up in Jonah House, a faith-based community of peacemakers in Baltimore, with internationally known activist parents Phil Berrigan and Liz McAlister providing strong ballast when not spending time in prison for nonviolent civil disobedience. I wanted to know what formed the vibrant Frida Berrigan, with whom I work on the National Committee of the War Resisters League. I learned about Frida’s birth in a basement, about Jonah House folks reading the Bible before days of work as house painters or being arrested at protests, about Frida and her sibs watching television on the sly, about the nitty-gritty of dumpster-diving at Jessup Wholesale Market.

But I learned much more from It Runs in the Family, and the “more” is at the heart of this fascinating book, which blends memoir, parenting advice, and connections between the questions parents ask about their children and the questions we should ask about the world. Phil Berrigan and Liz McAlister taught their children about the woes and warfare of the world; in this book, Frida also gently teaches us, while describing both her life as a child and her life as a mother to Seamus, Madeline, and stepdaughter Rosena.

SOME OF THE WORLD’S oldest spiritual music has been recorded, and thus preserved—just in time—thanks to a punk-rock drummer/photographer.

The ancient city of Aleppo, Syria, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and considered one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. Since 2012, when the Syrian civil war moved in to the area, Aleppo has been ravaged by fighting, and many of its inhabitants killed or made refugees.

Several years before the war began, Jason Hamacher embarked on an accidental odyssey to capture the sights and sounds of Aleppo, not knowing he might be the last to do so before the Old City, the historic city center, was destroyed.

Hamacher moved to Washington, D.C., in his teens and spent his high school years exploring a dual identity that would stick: Christian and son of a Southern Baptist preacher, and drummer in D.C.’s vibrant hardcore punk scene. Since 1993, he has recorded and toured with Frodus, Decahedron, Battery, and Regents. When he found himself between bands in 2005, he and some fellow musician friends who were also Christian vowed to search for new sounds in old spiritual music.

Soulful Protest

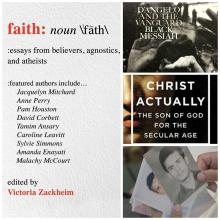

R&B singer D’Angelo ends a 14-year hiatus with the album Black Messiah, on which he sings of prayer, love lost, climate change, race, and violence. He asks, “In a world where we all circle the fiery sun / with a need for love / what have we become?” RCA

FOR TWO YEARS in a row we have seen significant films about oppression and struggle nurture public consciousness. Selma and 12 Years a Slave invite us to reimagine iconic moments closer than we usually think, their protagonists more like us. Slavery had not been portrayed in such visceral fashion in a mainstream film before 12 Years. Before Selma, images of Martin Luther King Jr. had never quite transcended the almost superhuman projections that accrue from his martyrdom and decades of being co-opted by cultural mavens from Apple to Glenn Beck.

These films create new benchmarks for the mainstream depiction of black history, black struggle, and wider perceptions. But entertaining portrayals of inspiration contain a powerfully dangerous substance that needs to be handled with care. The cathartic tears shed at a film about other people’s suffering and heroism can also be a narcotic, implying that the work has been done. Think of all the talk about freedom struggles after Braveheart, or challenging the principalities and powers after The Matrix. The problem was, most of it was just that. Talk.

MANY QUESTIONS remain about the alleged North Korean hacking of Sony Pictures and the U.S. response. But the Christmas controversy, apparently triggered by the Seth Rogen-James Franco satire film The Interview, has made one thing perfectly clear: A lot has changed on the internet since Al Gore didn’t invent it.

Back in the days of Gore, the net was an attempt to provide a secure and resilient military communications network during our Cold War with the Soviet Union. But by the turn of this century, it had become an unrivaled public forum for democratic activism and an absolute paradise for shoppers and porn addicts. Now the internet is getting back to its military roots. It is both the weapon and the battleground for United States’ simmering low-level wars with not only North Korea, but China, Iran, Russia, and anyone else who gets in the way.

For several years there has been a steady trickle of back-page news stories about cyberwarfare. The Chinese military seemed to be hacking U.S. government and business sites for military and industrial espionage. Two years ago the Chinese were said to have hacked The New York Times in revenge for that paper’s reporting on the financial corruption of China’s leadership. North Korea has allegedly attacked banking networks in South Korea. Attacks said to originate in Russia have hit U.S. and European energy companies. In 2009, the ante was upped when the U.S. and Israel unleashed the Stuxnet virus to sabotage the Iranian nuclear program. The virus destroyed Iranian centrifuges, but it also escaped to the broader internet and sabotaged computers at the U.S.-based Chevron oil company.

MARILYNNE ROBINSON’S Lila is the love story we thought we already knew, but didn’t. Lila takes us back to Gilead, Iowa, the same setting as Robinson’s novels Gilead and Home, describing the backstory and courtship of old Rev. Ames and the much younger Lila from a completely new point of view.

In Gilead, Ames describes his immediate, unlikely love for Lila, the hard-working wanderer. But Ames’ description of the feeling of love is more vivid than his description of the woman he loves.

The reverse is true in Lila. We learn Lila’s story through thick third-person prose. Robinson’s narration often reflects Lila’s stream of consciousness—a scattered, questioning pattern of thought, apt for a woman digesting the idea of small-town permanency after an exciting, scary, shame-filled life on the road. In the novel’s opening scene, Lila is just a small child, neglected and dying on the front steps of her house. Doll, a loving and hardened itinerant, kidnaps her just in time. It’s unclear if Doll stole or saved Lila. We can’t ever be sure. Either way, her love for Lila is fierce, and Lila comes to depend on it as they travel around the country, living off of door-to-door labor and inside jokes.

THE LAST THING that Ben Lowe could be accused of is “slacktivism,” which, as he describes in his latest book, Doing Good Without Giving Up, happens when we complain and point fingers about justice issues while being slow to take constructive action to address the situation.

From running for Congress at age 25 to helping to ignite a grassroots student environmental movement, Lowe’s track record for tackling complex and thorny problems where others would throw up their hands is remarkable. Even more remarkable is that after nearly a decade of such work, Lowe retains a gracious hope and steadfast sense of calling, despite being told by other Christians that he was being deceived by the devil, weathering bouts of burnout and depression, and continually facing entrenched systemic problems. This is why I trust him when he writes to encourage those of us whose hearts are heavy for the injustices in the world but often find ourselves stuck in the initial “slacktivist” inertia or dragged down later by opposition, burnout, and cynicism.

In Doing Good, Lowe outlines a sustainable impetus for social action and offers practices to sustain ongoing activism. We cannot be motivated by the desire to see dramatic change, he says, because this only “points people to ourselves and idolizes the change we seek.” It also ultimately lacks staying power. Instead, Lowe calls us to pursue faithfulness in our social action, which “points people to Christ ... and is ultimately the best—if not only—way to bring about the change God seeks.” Staying faithful, which the second half of the book covers, requires a continual reorientation to Christ as center through such practices as repentance, Sabbath, contemplation, and community.

LEONARDO BOFF’S Francis of Rome and Francis of Assisi: A New Springtime for the Church offers intriguing portraits of the current bishop of Rome and the saint that is his namesake. The book provides an introduction to these two extraordinary figures and includes a brief overview of the papacy, tracing how the office of the bishop of Rome eventually became the infallible pope.

The Roman Catholic Church depicted through Boff’s eyes is a church in crisis, reeling from the Vatican Bank and clergy sex abuse scandals. The institution and leadership have lost credibility in the eyes of many and the Roman curia is in need of reform. Yet this crisis is tempered by the election of Jorge Mario Bergoglio as pope, which for Boff fuels a tangible optimism for the church’s future.

Both men in these pages are called to the work of reform. Francis of Assisi’s conversion began when he heard a crucifix in a small church say, “Francis, go and restore my house, because it is in ruins.” Boff depicts Pope Francis as receiving a similar call, to reform the church so that it becomes a church that is poor, emphasizing humility and charity. Boff raises both men as models of living with the poor and like the poor, citing the now famous example of Francis going to pay his hotel bill after being elected pope.

THE GRAINY, STUTTERING surveillance footage shows police milling about, offering no medical assistance to the 12-year-old boy, Tamir Rice, one of them has just shot. They only spring into action when the boy’s older sister runs into the frame toward her brother. An officer tackles the girl, knocking her back in the snow, then cuffs her and puts her in the patrol car, only a few feet from her dead or dying brother.

This extended footage, released in January, and bystander cell phone footage from a few minutes later with audio of the sister wailing over and over “they killed my brother,” brought into my head the Good Friday spiritual “Were You There?” It was another moment, in months of unrest over police killings of black adults and children, when the question pressed in on me as a white person. “Were you there? Were you there when they choked my father dead? Were you there when they shot my son? Were you there when they killed my brother? Were you there?”

While books and other cultural works are no substitute or shortcut to the spiritual work of true repentance and detoxifying from cheap grace, they can be means of deepening understanding and finding the resolve to take action. Along with the film Selma, following are some of the artistic resources I’m turning to this Lent.

Living God's Reign

In Witnessing: Prophecy, Politics, and Wisdom, edited by Maria Clara Bingemer and Peter Casarella, international scholars write on many aspects of Christian witness, including martyrdom (especially Catholic martyrs in El Salvador), personal narrative, the interlocking realities of God’s beauty and justice, and intercultural dialogue. Orbis

THE WEEK leading up to the Michael Brown non-verdict was one in which race was at the forefront of daily life, at least as much as it was in the ancient days of my Mississippi upbringing.

You could say that week started with President Obama’s executive action on immigration. The next morning, I did household chores and listened to NPR coverage of the often-heated reaction to the president’s speech. The next day, my wife and I drove into Louisville to see Dear White People, Justin Simien’s devastatingly clever and thoughtful take on racism and identity politics among the Obama generation.

The movie made me laugh (at a volume embarrassing to my poor spouse) and even applaud in the middle of a crowded theater. It also left me pondering the persistence of the white supremacist virus in the American body politic. Over the past half-century, the film suggests, it may have evolved into a weaker strain, but it’s still lurking in there, and it can still make us sick.

USERS OF MAPS—that’s all of us—may suppose that what we see is factual, accurate, bias-free. Of course location, distance, elevation, and comparative importance are reliably shown!

Not so fast, says social activist and pastor Ward L. Kaiser. A map may be “right” in some ways but still dangerous to the way we live in the world.

Why? Because maps are layered with meaning. Surprisingly, their most important messages may lie beneath the surface. In his full-color book How Maps Change Things, Kaiser helps the reader to dig in and discover some of those hidden, mind-bending messages.

As a college chaplain I am acutely, sometimes painfully, aware of the often-hidden narratives and symbols that define us as individuals and as a culture. This book has helped me analyze how maps—an increasingly pervasive form of symbolic messaging and storytelling in our time—connect us to power and privilege or consign us to society’s also-rans.

PREACHERS, politicians, and other public speakers know that a story is often the best way to get a point across to their listeners. In his itinerant ministry, Jesus was no exception. Some of his most important teaching was contained in stories—parables. Yet often we do not take them seriously enough to seek what he was really saying. Two thousand years of Christian theology has also obscured his original intent, often by considering them to be allegories rather than stories.

In that process, anti-Jewish stereotypes and prejudices have too often come to dominate the interpretation of the parables. Any villain is seen as representing Judaism, while the hero or victim represents the church—and, of course, in this framing God is on the side of the church. This often-unconscious bias affects how we read and understand the story and obscures Jesus’ message.

Professor Amy-Jill Levine, in Short Stories by Jesus, aims to correct that. As a Jewish New Testament scholar teaching at a Christian divinity school, she is uniquely situated to place Jesus and his teaching in their historical and cultural context. Jesus was a first-century Jew speaking to other first-century Jews. If we do not understand that starting point, we cannot understand Jesus or his stories. In an introduction not to be skipped, she points out that the parables often echo themes that appear elsewhere in Jesus’ teachings: economics, relationships, and, most important, prioritizing life in expectation of the coming kingdom of God. To make his point, he uses common, everyday examples of real-life characters and situations his audience would recognize.