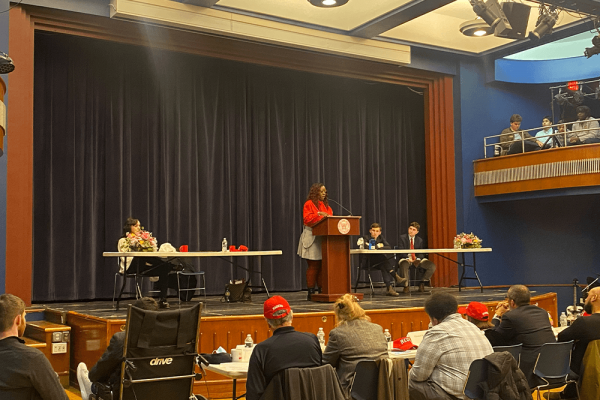

In New York City’s Upper East Side, just down the road from the Met Gala’s red-carpet celebrities and flashbulbs, around 400 high school students, teachers, alumni, parents, and formerly incarcerated people came to Regis High School’s auditorium on Monday night to listen to two high school debate students compete against two alumni of the Rikers Debate Project.

The debate on Monday focused on the question “Should cash bail be abolished?” A coin toss determined which position the teams would argue.

Since the debate was done in an educational context, the results of the coin toss, the sides assigned, and the contents of their arguments were off the record, by request of Regis High School. Although the contents of the debate were off the record, observers told Sojourners that the encounter itself was inspiring.

“Although I learned a lot about bail reform from the evidence presented by both sides, I was even more inspired by the personal stories and successes of the Rikers debaters,” said high school senior and debate team member Brian Mhando who was in the audience.

At the Monday event, Pat Andriola — a co-founder of the Rikers Debate Project — told the audience that debate teaches skills to make your voice not just heard, but persuasive.

Kaamilya Finley, one of the Rikers debaters on Monday evening, joined Rikers Debate Project two years ago, when one of her classmates in Georgetown University’s year-long re-entry program for formerly incarcerated individuals told her she’d be an excellent debater.

While initially resistant, Finley said that debate has taught her valuable re-entry skills.

“Debate is negotiation,” she said. “I’m negotiating with society right now to get my life back.” And she thinks that debate has helped her see the world beyond her own perspective and learn why people think the things that they do, even if she disagrees. “Debate teaches me to see things from both sides, to understand an issue from another person’s point of view,” she added.

In order to achieve a healthy, integrated community, Andriola said it’s paramount to truly listen to the voices of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people.

“We need to have grace to rehabilitate people,” Andriola told Sojourners in a phone interview, “not just nominally, but to listen to them and make them a substantial part of the community.”

The Rikers Debate Project was founded in 2016, and Monday’s event was sparked when Andriola met Regis student Will Liao, a member of the Regis High School debate team. Liao, a senior at the school, is a student leader of Regis at Rikers, a club that brings students to Rikers to build fellowship with inmates. He recently led a supply drive for those imprisoned with the help of the Jesuit-run ministry Thrive for Life, which ministers to currently and formerly incarcerated people. Through these ministries, Liao said he witnessed the isolation incarcerated people are subject to and has been moved to act. After hearing about incarcerated men writing letters to themselves in order to have a piece of mail to collect, Liao helped Regis at Rikers put together a pen pal program.

Regis High School was founded on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in 1912 by a donation from Julia Grant, the widow of NYC’s second Catholic mayor, Hugh Grant. The Jesuit school provides tuition-free education for young Catholic men and maintains a school-wide commitment to social justice. Liao’s teachers celebrated his decision to engage with the Rikers Debate Project as an example of this commitment.

“Will really took the lead on this project,” said his debate coach, Eric DiMichele, director of admissions at Regis, who has been coaching the highly competitive team for four decades. “It’s an example of that Jesuit school commitment to social justice.”

After hearing six speeches of arguments, a panel of 13 judges cast votes to decide the winner. Judges included Atlantic staff writer Elizabeth Bruenig and New York City Council Members Carlina Rivera and Gale Brewer.

One of the judges, Quintin Murray, is a resident at Ignacio House Studies in the Bronx, as he earns his bachelor’s in social work at New York University and continues his work as a re-entry consultant.

“I felt honored to be included as a judge, among assemblywomen and district attorneys,” he said.

He told Sojourners he has always loved debates and that forming arguments on paper in his coursework has helped him hone his debate skills. He noted tonight as a moment of growth for himself as a judge, as he put aside his own experience and biases and let himself be persuaded by the debaters.

“I used to be quick to be judgmental about a lot of different things,” he said, “but now I try to listen to others — listen to their stories.”

Editor's note: This article was updated at 12 p.m., May 5, to correct the number of judges who participated in the debate. There were 13 judges, not 10.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!