Jan 9, 2020

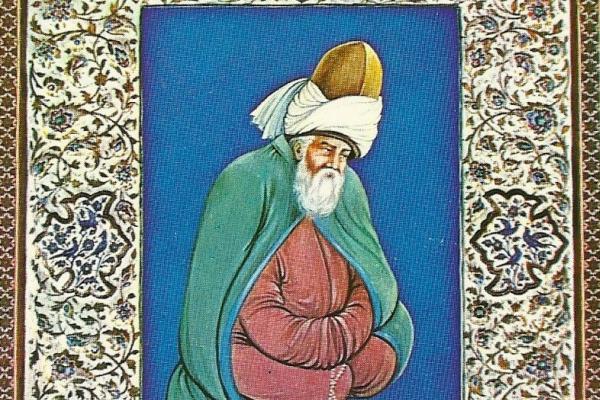

Today, the United States and Iran are two countries on the precipice of war with ruling elites who quote Rumi.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login

Today, the United States and Iran are two countries on the precipice of war with ruling elites who quote Rumi.