Culture Watch

I MET MARKKU and Leah Kostamo of A Rocha, an international Christian environmental organization, on the set of a television show in Toronto. The show was Context, hosted by the welcoming Lorna Dueck. This show explores the stories behind the news from a frankly Christian viewpoint.

I had been invited to talk with Dueck about my MaddAddam future-time book trilogy, and in particular about characters in the second book, The Year of the Flood, called the “God’s Gardeners,” a green religious group that raises vegetables and bees on flat rooftops in slums. It is headed by a man called Adam One and includes a number of ex-scientists and ex-doctors who have withdrawn from a too powerful, greedy corporate world in which they can no longer function ethically. The God’s Gardeners group represents the position—probably true—that if the physical world is going to remain possible for human life, religious movements of many kinds will be an important element. We don’t save what we don’t love, and we don’t make sacrifices unless “called” in some way to make them by what AA refers to as “a higher authority.”

Dueck and I talked a little about that, and then—surprise—right before me were two people who closely resembled the God’s Gardeners of my fiction. Leah and Markku Kostamo are walking the God’s Gardeners walk—through A Rocha, a hands-on creation-care organization. A Rocha’s origins go back to the Christian Bird Observatory (cf. St. Francis) founded on the coast of Portugal by Peter and Miranda Harris in 1983. Leah met the Harrises in 1996 when she took a class they were teaching at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia, and A Rocha Canada was born. It was soon augmented by Markku, an environmental scientist. A Rocha is now running 20 projects around the globe, engaged in everything from habitat restoration to organic community farming.

EVERY SO often an extraordinary book appears with potential to bring change—or at least advance justice by mitigating nationalism or prejudice. Rabbi Michael Lerner’s Embracing Israel/Palestine: A Strategy to Heal and Transform the Middle East is such a book. The appeal is clear: Be both pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli and pray for the best for each.

The book is a gut-wrencher as it describes the results of cyclical violence and reaction that fuels descent into paralyzing trauma and anger for both Arabs and Israelis.

Lerner, an advocate for Middle East justice and founder of Tikkun magazine, speaks truth about the human-made tragedy of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. His transformative counsel about what people and nations can do to participate positively is desperately needed. Social justice advocates have been offered a candid and honest reprise of the tragic thinking and actions of oppressed people who should have known better than to visit the same on “the other.”

Lerner’s way toward peace is grounded in many years of living in and traveling to Israel/Palestine, loving the two protagonists equally, and constantly exploring his and others’ souls. In spite of the victimizing and traumatizing of both Jews and Arabs, he remains hopeful. Embracing makes for a compelling and even inspiring read. I devoured most of it in two sittings, captivated by Lerner’s vision.

NO ORDINARY MEN: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Hans von Dohnanyi, Resisters Against Hitler in Church and State is a tightly woven story framed by the sophisticated historical analysis of its two authors, former senior Farrar, Straus, and Giroux editor Elisabeth Sifton (daughter of theologian Reinhold Niebuhr) and Columbia University professor emeritus Fritz Stern, a famed German scholar. The book profiles two brave young men—Bonhoeffer, a theologian and minister deeply involved in fighting the Nazis’ efforts to control the German Protestant churches, and Dohnanyi, a brilliant lawyer (son of Hungarian composer Ernst Dohnanyi) working in the German Ministry of Justice, who used his key position to methodically collect evidence against the Nazi regime.

Sifton and Stern portray Dohnanyi in detail as a leader in the small but high-powered German resistance movement. Brig. Gen. Hans Oster, a resistance member, hired Dohnanyi away from the Ministry of Justice ostensibly to help run the Abwehr, a German military intelligence organization that was also the center of the anti-Hitler resistance, in 1939. Dietrich Bonhoeffer was then recruited by Dohnanyi to be part of this team. Dohnanyi’s wife, Christine (Bonhoeffer’s sister), is also revealed as a significant influence on and aide to her husband.

The slim, 157-page volume is an important new historical work in the growing field of research on the German resistance movement during World War II. It is a penetrating look at Dohnanyi’s dangerous operations against the Nazis with historical perspective that other books on him and Bonhoeffer lack. Earlier biographies, written mainly by church people, more or less emphasized Bonheoffer as a singular hero fighting Hitler. Bonhoeffer was indeed very brave and traveled thousands of miles abroad while working as an agent for the Abwehr, but he was just one of a circle of resisters.

THE DOMINANT cultures of North America have long struggled to take responsibility for the suffering and injustice inflicted upon the Indigenous Peoples of the continent. The archetypal “us/them” story of cowboys and Indians remains at the core of North American national identities, from derogatory sports mascots and symbols such as the Washington “Redskins” and the “Chief Wahoo” character of the Cleveland Indians to the ignorant “redfacing” by non-Indigenous partygoers and trick-or-treaters in contrived Indian outfits. And this situation is nowhere near ending, despite many years of cultural sensitivity training and education.

Such overt racism should never be acceptable today. Yet it persists in regard to Indigenous Peoples. Why is this? As one friend remarked to me, most modern-day Americans believe injustices done to Indigenous Peoples to be a thing of the past.

But are they? Steve Heinrichs, director of Indigenous relations for the Mennonite Church in Canada, has brought together nearly 40 theologians, activists, writers, and poets—half of whom are Indigenous—to create Buffalo Shout, Salmon Cry: Conversations on Creation, Land Justice, and Life Together, a challenging anthology on Indigenous-Christian relations, stolen land, racism, and the impending environmental crisis that we all must face together.

THE MOST common image of the assassination of President Kennedy is embedded in the collective consciousness due to the fact that it was the subject of what may be the most-seen film in history, Abraham Zapruder’s 26-second home movie, grainy and garish in color and fact. The more recent eruption of reality television may have left us nearly unshockable, but a long, hard look at Zapruder’s short, hard film is still horrifying. The most provocative context in which I’ve seen the film located is Stephen Sondheim’s meaty musical Assassins. The Broadway production had Neil Patrick Harris as Lee Harvey Oswald with the film projected onto his white T-shirt. That the show took place at Studio 54 served to underline the demonic bargain at the intersection of the military-industrial-circus complex: The nightclub theater location satirized the fact that our stories about killing can either critique the cultural appetite for destruction or serve to perpetuate more of it as a form of entertainment.

If Assassins was the most provocative screen for the Zapruder film, the most politically complex is Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie JFK, now being rereleased to mark the assassination anniversary. It’s one of the greatest examples of cinematic craft applied to polemic (current examples are Captain Phillips and 12 Years a Slave)—edited like a dance, with a television miniseries’ worth of big name actors (Jack Lemmon, Sissy Spacek, Walter Matthau, Donald Sutherland, John Candy) in small roles holding up the edifice of big speechifying done by Kevin Costner and Tommy Lee Jones. It’s a thrilling film, and it has intellectual substance—the point is not whether or not the conspiracy theory posited in JFK is true, but that human beings “sin by silence” when we should speak.

FOR SEVERAL years now, a debate has raged over the issue of “net neutrality,” pitting media reformers, digital libertarians, and “content” companies such as Amazon and Netflix against old-school telecommunication giants such as AT&T and Comcast, with the Federal Communications Commission serving as an erratic referee.

Sometime early this year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia may settle the question when it decides the case of Verizon vs. the FCC. If the court decides in favor of Verizon, big telecom companies will have won the right to decide what digital content we can receive, especially when it comes to video and other bandwidth-intense media.

Simply put, the issue in the Verizon case is whether broadband internet will follow the “common carrier” precedent applied to telephone lines and the electricity grid or the model of cable TV. The common carrier principle guarantees equal access to necessary public utilities. Applied to the internet, this has meant that service providers simply supply the fiber-optic cable or wireless spectrum, give equal access to all content providers, and charge the final recipient of the data (you and me) a fee that covers the cost of maintaining an adequate network.

In the cable TV business model, the provider controls the network of fiber optic cable and the content that goes over it. The cable company decides which channels are included in the basic package, which (like HBO) are purchased separately, and which will be unavailable at any price. If you want Al Jazeera instead of Fox News, too bad—it’s a take it or leave it package.

Spirit Connections

Some Western and global South churches have established “sister church” relationships as a more mutual alternative to the old mission field approach. Drawing on fieldwork and interviews, Janel Kragt Bakker studies the give and take of this model in Sister Churches: American Congregations and Their Partners Abroad. Oxford

Border Clashes

The documentary The State of Arizona captures multiple perspectives on undocumented immigration in the aftermath of Arizona’s controversial Senate Bill 1070, dubbed the “show me your papers” law. Directed by Catherine Tambini and Carlos Sandoval, it will premiere on PBS’s Independent Lens series on January 14 (check local listings). communitycinema.org

I MEET Yehoshua November in an empty classroom in Touro College in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he teaches. The chairs and desks are piled to one side, like a barricade. We sit in a clearing beside the clutter, talking about his place as the only Hasidic poet—he is a 34-year-old member of the Lubavitch sect—on the American literary landscape, an entity ruled largely by secular academics far removed from the realities and sensibilities of ultra-orthodox Jewish observance and mysticism.

“They are the rabbis of poetry,” November laughs. He laughs so hard he doubles over in his chair. His laughter is as strange as it is infectious. Yet in all of God’s Optimism, his book that was short-listed for the 2010 LA Times Book Prize, there is not a single laugh line. His poems are serious, if lightly held narratives, some parable-like, most down to earth with a longing for heaven.

“Poetry is their vision of spirituality, their own religion, and they don’t want traditional religion brought in,” he says.

Even November’s long, reddish beard seems delighted at their rebellion against traditional religion. An antinomian Hasid and unashamed of it.

When I first read God’s Optimism, the poem I kept going back to was “Baal Teshuvas at the Mikvah” (baal teshuvas are secular Jews who return to religious observance), a poem of solidarity with those intimate others who came to Hasidism through the tunnel of the profane, commonly marked by drug use and sexual looseness, for the sake of spiritual passion held within a net of restrictions.

THE DAYS shorten and the scriptures get wild and woolly and Advent begins. Meanwhile, the secular holiday season builds in a frenzy of car commercials (does anyone really get a car for Christmas?), sale flyers, and often-forced cheer. Here are a few books—memoirs, spiritual writings, and art—that can be interesting, grounding, and inspiring companions for a complicated time of year. (They also are much easier to wrap than a car.)

Life stories

Good God, Lousy World, and Me: The Improbable Journey of a Human Rights Activist from Unbelief to Faith, by Holly Burkhalter. Convergent Books. Decades in political and human rights work convinced Holly Burkhalter that there couldn’t be a loving God—until she became a believer at age 52.

Hear Me, See Me: Incarcerated Women Write, edited by Marybeth Christie Redmond and Sarah W. Bartlett. Orbis. I was in prison, and you listened to my story. Moving works from inside a Vermont prison.

God on the Rocks: Distilling Religion, Savoring Faith, by Phil Madeira. Jericho Books. Nashville songwriter, producer, and musician Phil Madeira offers lyrical, wry observations on faith and life, from his evangelical roots to musing on a God who “knows she’s a mystery.”

I CAN’T WRITE a completely unbiased, academic review of this book: Nora Gallagher is a friend, and I know the medical world that she must still navigate, and how wonderful it is when you arrive at the Mayo Clinic. This book is for anyone who plans to die one day and wants to live daily with purpose and with a real God. Those who are or have been physically ill will find a kindred soul in Gallagher, while the healthy will wonder how they will handle the sad, sympathetic gazes from others in the pew when their names are placed on the prayer list.

When she is 60, the vision in one of Gallagher’s eyes begins to fail. She limits the use of her one good eye for fear of losing sight in it too. Not so bad, you might think—except that as a writer, seeing is key to paying for the medical tests and travel she will endure for two years.

Of course all good patients become writers in a way. At first you take random notes in scattered notepads. Finally you redefine yourself as a full-time patient whose life demands documentation of every symptom and test in a little black book that becomes your constant companion. You have now entered what Gallagher calls Oz, the land of illness.

For Gallagher, Oz is strange. Oz is blurry. She is lonely. She is a patient not a person. Oz has many disrespectful, condescending doctors working in machine-like hospital systems that allow 10 minutes for a consult; they must get to the next patient, not solve the mystery of her now-painful, debilitating state.

JAMES DOBSON and Kurt Bruner get three things right in their recent novels Fatherless and Childless: Euthanasia is wrong, married couples should make time to have hot sex, and stay-at-home moms should get some respect.

Pretty much everything else in the novels, the first two-thirds of a trilogy (book three, Godless, is due out in May 2014), is way off and internally incoherent. The plot starts in 2042, when an aging population and economic malaise have motivated the government to legalize euthanasia. Businessman Kevin Tolbert, recently elected to Congress, lectures his peers about the need to stop euthanasia and encourage parenthood in order to revive the economy. His wife Angie’s high school friend Julia Davidson, an allegedly progressive and feminist reporter, is assigned to write a story about him (lecture alert). Meanwhile Kevin and Angie struggle (with mercifully few lectures) with their third child’s diagnosis of Down syndrome. Subplots deal with a disabled teen and an elderly dementia victim who turn (or are pushed) to euthanasia.

Actual euthanasia, as disability-rights groups such as Not Dead Yet have documented, often turns on society defining “dignity” according to physical ability and health instead of the innate value of a human being. These novels, however, ask us to believe the main impetus for euthanasia would come from the drive to reduce the federal deficit, to deal with “swelling entitlement spending.”

What spending? The novels’ elderly and disabled characters are drawn or pushed toward euthanasia because of family financial troubles: There is no mention of any Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid help going to any of them.

IN THE FOREWORD to Where Justice and Mercy Meet: Catholic Opposition to the Death Penalty, Sister Helen Prejean writes, “Welcome to the pages of this amazing book.” Her hospitable remark is not an exaggeration. I have written articles, taught classes, and spoken to church groups about capital punishment; in my judgment this book is the most accessible resource now available for engaging, informing, and perhaps even transforming how readers view the death penalty.

Where Justice and Mercy Meet was edited by death penalty activist Vicki Schieber, philosopher Trudy D. Conway, and theologian David Matzko McCarthy. The book is the product of two years of interdisciplinary courses, discussions, projects, and research—in sociology, political science, philosophy, economics, theater, ethics, and theology—at Mount Saint Mary’s University in Emmitsburg, Md. While the book has a Catholic focus, it should be useful to Christians of all stripes and others interested in addressing this issue.

The volume is divided into four parts. Through skillful section and chapter introductions and segues, the editors have done a fine job of creating an integrated whole. Relevant questions for discussion and action tips make the book perfect for study groups in churches and for the university classroom.

Part I, “The Death Penalty Today,” exposes the realities of the dominant current method of execution (lethal injection), surveys the history of the death penalty debate in the U.S., and suggests the significance of reading or hearing the stories of those affected by murder and capital punishment. Kurt Blaugher’s chapter, “Stirring Hearts and Minds,” meditates on the role of drama in allowing these stories to capture and broaden our imagination, to stimulate reflection, and to compel us to take action for social change. Indeed, stories—from real life as well as from film and literature—surface throughout the volume, with the most moving and memorable ones being the experiences and voices of those whose loved ones were murdered.

I RECENTLY saw a photograph of me taken on the day I was born: two weeks premature, swaddled, peaceful, vulnerable, beautiful—pure potential. I wanted to travel back in time to give the little guy some advice and protect him. Most of all I wanted him to experience the things I missed—those that only seem to come to our attention with the benefit of hindsight. I wanted him to take more risks for the good, not worry so much, be more open to receiving love, take more walks in fields and on beaches, and avoid a thousand mistakes. I wanted him to be different.

While wanting to undo history is probably a human universal, it can also be a kind of psychic violence, emerging from the notion that there is such a thing as the person we were “supposed” to be. Indulging this notion led to me projecting it onto three intriguing films. Short Term 12 is a lovely, painful story of recovery from childhood wounds. In Seconds, the newly restored melancholic science fiction tale of human engineering from 1966, Rock Hudson brilliantly imagines what happens when you convince yourself that superficiality is depth and exchange the life you have for cosmetic “transformation.”

“I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.”

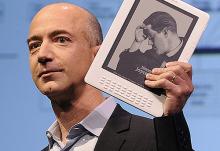

THE QUOTE IS from Charles Foster Kane, the character based on William Randolph Hearst in Orson Welles’ 1941 classic Citizen Kane. But it could have been Amazon kingpin Jeff Bezos this August when he bought The Washington Post. What can you get for the man who has everything? Maybe he’d like a newspaper to play with, preferably one with global political clout.

Unlike Charles Foster Kane or Rupert Murdoch, Bezos seems disinclined to monkey with the content of the Post’s coverage. His business interests may require certain government policy directions—i.e. free trade and no unions—but on those questions the Post is already with him. They differ on net neutrality (the concept that providers of internet access should not be able to discriminate against or give preference to specific internet service or content providers), so that will be one to watch. But Bezos comes to the Post saying he essentially agrees with the paper’s politics. In fact the Post’s reputation as a credible voice for corporate centrism seems to be a large part of what Bezos wants for his $250 million.

This may explain why Bezos, a titan of the rising digital world, would weigh himself down with an ancient “legacy” institution. It’s an old American story. When you get rich enough (Bezos’ fortune is estimated at $27 billion), you don’t want more money, you want power and respect. The same process played out with the robber barons in the last century. It’s just that today the evolution happens much faster. It took three generations for the Rockefellers to go from oil tycoons to philanthropists and politicians; contemporary barons such as Bezos and Bill Gates have made the switch within a couple of decades.

Still Shining

David Hilfiker is a retired inner-city physician and writer on poverty and politics who has Alzheimer’s. He writes about his experience, with the hope of helping “dispel some of the fear and embarrassment” that surrounds this disease, on his blog “Watching the Lights Go Out.” www.davidhilfiker.blogspot.com

Transported

Laura Mvula is a British, classically trained musician, songwriter, and former choir director whose debut album,Sing to the Moon,is a lush fusion of soul, jazz, gospel, and pop. While not overtly “about” faith, her arrangements are imbued with spiritual longing and visions of beauty. Columbia

OUR BODIES AND the land are one. Move the earth with your body, dance on it, farm in it, play with it; our final return to it is sacred. The soil is made of clay, like you and me—hydrocarbon molecules, layers of geological and muscular formations, alive. The soil, mountains, and valleys are layered with time like our layered muscle tissue. We dance on the earth in the face of death, for the healing of ourselves and the healing of the land, connected as farmers, dancers, painters, musicians, and lovers of the goodness of the good green earth moving through lament. Our bodies and the earth are one and their healing and grieving are interconnected.

January 2011, around the corner from my house, Anjaneah Williams was murdered, across the street from Sacred Heart Church, pierced in the side, at 2 p.m., walking out from a sandwich shop. It was a Thursday. She died six hours later at Cooper Hospital in the arms of her mother, before the children who deeply loved her. One of the gunman’s stray bullets shot across the street through the stained glass at Sacred Heart. Anjaneah’s death reverberated in the air, an exploding, echoing canyon; a screaming mother in a vacuum, unheard and deafening. Her murder was one of 40 in the neighborhood in the near half-century since the shipyard closed. Forty people on the sidewalks, on the lots where houses once stood, in a neighborhood with 28 known environmentally contaminated sites.

SOIL AND SACRAMENT is Fred Bahnson’s story of finding God through sustainable farming. A trained theologian, he learns to best live out his faith with shovel in hand, practicing a method of permanent agricultural design principles called “permaculture.”

We follow him through the liturgical year on an agrarian pilgrimage from one faith community to another, digging into the big question of how to best love his neighbor. His answers are uncovered through building relationships and healthier soil, communing with others and his Creator in the field. From jail cell to monastic cell, from a rooftop in Chiapas to his four-season greenhouse, Bahnson finds the intersection of community and solitude between the field rows. Just like the first Adam from the adamah (earth), we learn how to give more to the soil than we take away and to reverently observe the garden as fruitful and multiplying. “Human from humus”—he had me at hugelkultur. (Look it up—it’s really cool.)

Bahnson begins his pilgrimage in a Trappist monastery in South Carolina during Advent, joining the brothers in prayer and mushroom-growing practices, entering the dark cold winter silence of vigils and the soil. Bahnson then flashes back to 2001, to Holy Week in Chiapas with a Christian Peacemaker Team accompanying the Mayan Christian pacifist civic group Las Abejas—“The Bees.” In Chiapas we sit and eat with Bahnson on Maundy Thursday, corn tortillas and slow-cooked black beans made into holy elements, partaking of an “ancient and unnamed liturgy,” eating our way into mystery. Bahson ordains the creatures of the earth as perennial ministers of the soil, notes the transubstantiation of seed and potluck as Eucharist. He writes of beginning to think of growing food as the embodiment of loving his neighbors, the journey of the liturgical calendar through the mystery of soil. The book is a slow dance, a cosmic one-turn around the sun.

IN MY MEMORY from nearly 50 years ago, the great pitcher Sandy Koufax is going against my Phillies in the old Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia. The records show that such a game occurred on June 4, 1964, the right year for my memory, so it is possibly correct. But I cannot prove I was there that day, nor can anyone prove I wasn’t. For me, it has entered the realm of myth—I may not actually have been there, but in my memory I believe I was. In a similar manner in religious experience, historical events originally recorded as perhaps inexact memories come to be believed as literal truths.

In Baseball as a Road to God, John Sexton uses the categories of the study of religion to explore the meaning of baseball. Sexton, president of New York University, has taught a popular seminar on this topic for more than 10 years, and in this book collects the essence of those classes.

For a baseball fan, the well-told stories of historic players, games, and seasons are by themselves worth reading and will evoke many memories. But rather than a random collection of stories, Sexton groups them in topics—sacred place and time, faith and doubt, conversion and miracles, blessings and curses, saints and sinners—illustrating each with fitting examples. Underlying it all, he proposes, are two words and concepts that link baseball and religion. Both illustrate the significance of the ineffable, “that which we know through experience rather than through study, that which ultimately is indescribable in words yet is palpable and real.” And both have moments of hierophany—a term devised by religious historian Mircea Eliade to signify “a moment of spiritual epiphany and connection to a transcendent plane,” a “manifestation of the sacred in ordinary life.”

THIS SHORT VOLUME by Jacqueline Battalora, a professor of criminal justice at St. Xavier University in Chicago, addresses a very important topic in American history and society: The legal, social, and political invention of the category of “white people” as a privileged group, which defines them as the normative Americans over against others, variously defined as “black,” “colored,” “Indians,” and “mulatto.”

When English settlers founded the New England colonies, they referred to themselves as British. As more people from other countries of Western Europe arrived in the area, they tended to group those they saw as similar to themselves as Christians, Germans, etc.—the term “white” was not used—over against “Negroes,” Indians, and rival colonizers such as the Spanish and French.

The term white was first used in colonial law after Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, during which some African and European indentured servants formed an alliance. Virginia’s colonial leaders responded with a package of laws that created a racial caste of African-descended slaves, distinguished from European servants. These laws decreed that African slaves could not be freed and free Africans could not hold office, serve in the army, or hold European bond laborers. This group was thus disprivileged, in contrast with those of European descent who were defined as “white.”

LEE DANIELS’ The Butler, a century-spanning tale of race in the United States and service in the White House, is a dream of a film—by turns historically realistic and magically fable-like. It’s a perfect companion piece to last year’s Django Unchained, in that case a movie whose tastelessness wrapped up as fabulous entertainment forced audiences to engage with a deeper level of the shadow of U.S. history.

Based on the story of Eugene Allen, a black man who served multiple presidents in a White House that took its own time to desegregate its economic policies for domestic staff, The Butler begins with a rape and a murder of plantation workers by the son of the boss. The ethical quality of the film is immediately apparent. This horror is not played for sentiment, nor even spectacle, but to evoke the very ordinariness of monstrosity.

This makes The Butler a rare film: one more interested in confronting us with a kind of previously unspoken truth than in goading us to feel the catharsis of guilt-salving by association. (It’s the antithesis of films such as Mississippi Burning, which use white protagonists to tell black stories and appear to believe that we can somehow participate in the virtue of the civil rights movement just by watching a movie about it.) The makers of The Butler have told a kind of truth about the struggle for “beloved community” that has rarely been seen so clearly on multiplex screens. The film illustrates the serious and painful work of nonviolence and invites us to consider the political and cultural tensions within the black freedom struggle, while giving a more humane perspective on the presidency than is often the case. We can hope the door is now open to more reflective cinema about the unfinished business of the black civil rights movement, broken relationships, traumatic memory, and how we tell the story of who we are.