Spirituality

One sort of Christian believes taking Eucharist weekly saves her. Another Christian believes his confession of Jesus Christ as Lord saves him. Still another looks to his Baptism. Another to her participation in the body of Christ. One to his repentance. And another to her care for the sick, the hungry, the prisoner, and the poor.

We elevate one belief or practice over another, then divide ourselves as Christ followers by the priority we set when, in fact, all of these are taught as saving by Christ, who alone is our salvation.

Christ saves me, not the accuracy and purity of my beliefs. Christ saves me, not my works. Christ saves me, not the measure of my adherence to a doctrine or practice.

When all is said and done, many Christians tend to look to their habits, their faith, and their perseverance when it comes to salvation rather than to the work, belief, and faithfulness of Christ in us, over us, under us, and through us.

Bio: Carol Roth [Choctaw] is staff leader for Native Mennonite Ministries, a group that does liaison work between Native Mennonites and the broader Mennonite church. www.mennoniteusa.org/about/structure/related/

1. What are you most passionate about in your vocational role?

I’m passionate about working with the Native Mennonite people and helping them find a place in the Mennonite church. Unfortunately, some of the Native churches aren’t close to the Mennonite conferences, so you have to drive 800 miles to be connected to a conference, especially when you live on a reservation without internet or telephone. So my role is to connect the conference ministers and the conference with the Native churches and get them involved.

2. How did you come to straddle the Mennonite and Choctaw traditions?

When my twin sister and I were born [on a Choctaw reservation in Mississippi], my mom felt like she couldn’t give adequate care to two newborns. It happened that there were Mennonite missionaries who had moved nearby to help with the Choctaw group, and my parents asked if they could care for us for the winter. My parents realized how well they were taking care of us, so they asked if they could continue to care for us. My parents didn’t want them to adopt us, because they wanted us to keep our culture. So we grew up with the Mennonite missionaries, and then pretty much for all our lives attended one of the Choctaw churches.

THIS IS NOT a column full of hand-wringing about the moral decay of U.S. society. Nor is it about my concern for the souls of my fellow citizens who are atheists, agnostics, or some other stripe of nonbeliever. I am worried about the growing number of religious “nones” in the United States, but not for those two reasons.

Let me be clear about something before continuing: Many of the people I love and admire most are religious “nones”—those who indicate “none of the above” on religious preference surveys. They include people of high intellect, great sensitivity, and deep character. In fact, many of them could give lessons in such areas to some of the religious people I know.

What they do not do is build hospitals, schools, colleges, or large social service agencies. Such institutions (when not built by the government) have generally been founded and supported by religious communities in the United States. This is not so much because religious people are always better human beings; it’s because religious communities value and organize such work at significant scale.

Religious communities play a profound role in U.S. civil society. About one out of every six patients in the U.S. is treated by Catholic hospitals. Most, if not all, have some sort of explicit commitment to serving the poor because of their faith identity. There are nearly 7,000 Catholic grade schools and high schools in the U.S., and more than 260 colleges. This is to say nothing of the refugee resettlement, the addictions counseling, or the services for homeless men and battered women provided by Catholic social service agencies.

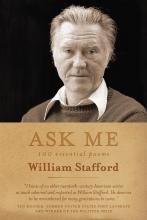

Miles of yellow wheat bend; their leaves / rustle away and wait for the sun and wind.

—From “A Farewell, Age Ten”

We wondered what our walk should mean, / taking that un-march quietly; / the sun stared at our signs—"Thou shalt not kill.”

—From “Peace Walk”

WILLIAM STAFFORD was a poet of the land and a conscience that fanned out over the land. Born in Hutchinson, Kan., 100 years ago—on Jan. 17, 1914—it was perhaps his early intimacy with space and sky that opened him to the mystery of human frailty.

At age 6, he saw two black students at his school being taunted by whites. He stood with them.

Another mystery: He who personifies the term national poet is largely unknown in his nation. Four new books (in his 79 years, Stafford published more than 50 books) published to coincide with his centennial might help redress this situation. Ask Me (Graywolf Press), from which the above excerpts are taken, brings to readers 100 “essential” Stafford poems dealing with his pacifism, his family, Native Americans, and the landscapes of his native Kansas and his adopted Oregon, where many centenary events are scheduled to take place.

IN HER LATEST book, Sara Miles—author of the spiritual memoirs Take This Bread and Jesus Freak—goes where traditional and liturgical churches don’t regularly go: into the streets to push the boundaries of public worship. City of God chronicles a day in the life in San Francisco’s Mission District, on one Ash Wednesday when Miles and others from St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church offer “Ashes to Go,” a growing national movement within the Episcopal Church to perform the imposition of ashes outside the church walls on the first day of Lent.

Ash Wednesday works on the street because it has a broad ability to speak to people with “different beliefs about God and very different relationships to the church.” Even so, carrying the observance away from the altar has generated critics. Some liturgists have wondered if, without a proper church context, “the ashes become a meaningless affirmation of our earthly life,” or whether regular folks on the street can really appreciate the profundity of the human condition and mortality without the church to explain it to them. Trusting that people on the street will “get it,” Miles embarked on a day of crossing the traditional borders of worship space to smudge foreheads in McDonald’s, taquerias, hair salons, and botanicas.

Miles finds that traditional observance of liturgies such as Ash Wednesday helps reclaim the public language of sin and repentance in a progressive way. This kind of re-evaluation of sin in common life led her to realize how she’s also fallen short of the call to solidarity and deep communion with the city. “I aspired to be the kind of neighbor who knew everyone,” she writes, “I yearned to be in real relationship.” But her admittedly self-satisfied sense of fellowship didn’t match up to her interactions. She hadn’t even bothered to learn the last name of a young Latino activist on her block and confesses, “I prayed for my neighbors, but not so much with them, and it made me uncomfortable.”

AN ASTONISHING aspect of the miracle that was the Exodus is the recorded “600,000 men on foot, not counting their dependents” (Exodus 12:37). A whole people uprooted themselves and moved into the unknown. This was displacement on a massive scale. Their readiness to move from the security of slavery, from the only reality they had known for four-and-a half generations, was more awesome than the willingness of Pharaoh to let them leave.

What organizer today would not grasp at the key to a process that would move enslaved people in the Egypts of today? ... But this is still the beginning. The 40 years of wandering in the wilderness may have been a punishment for their constant complaining.

In his New York Times column, “ Alone, Yet Not Alone,” David Brooks laments the “strong vein of hostility against orthodox religious believers in America today, especially among the young.” Even more disturbing for Brooks is that in his experience, the opinion of young people is too often justified. He observes that religious believers can be “judgmental,” “hypocritical,” “old-fashioned,” and “out of touch,” and he wonders why that’s so. Brooks, who is Jewish, knows that the Judeo-Christian tradition reveals a God who desires mercy and not sacrifice, who calls us toward a radical love that includes our enemies. As evidence of the core of orthodox belief, he offers two giants of the Judeo-Christian tradition, Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Augustine, who give testimony to lives of compassion and love inspired by devotion to the biblical God. Lives that tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty as essential components rather than disqualifiers of faith.

So what gives? Why do religious believers spend so much energy reinforcing their (our – I’m one of those orthodox believers) borders, building thicker and higher dividing walls designed to keep out the underserving, the sinners whom not even God can love? Just who is kept out varies widely, but it seems religious people are utterly convinced that they are on the inside with God. No doubt about it. Musing on this sad fact, Brooks comments:

There must be something legalistic in the human makeup, because cold, rigid, unambiguous, unparadoxical belief is common, especially considering how fervently the Scriptures oppose it.

Brooks is on to something here – there is something rooted in our “human makeup” that the Scriptures fervently oppose, but it is not legalism per se.

If any list has been overdone in the Christian blogging world, it's this list.

Just about every Christian blogger has done one, and if they haven't, they've thought about it and then thought better of it – because just about every Christian blogger has done one. (See what I did there?)

And yet, here we are.

You. Me. And my list of things Christians shouldn't say. Hmmmm – must be God's will. (And I just realized this list should have had 11 things on it. Oh, well. I have no doubt that it's on one of the lists out there!)

Folks who have just knocked back two drinks say they’re really aware of God at that moment.

And good sleep enhances a sense of God, joy, peace, and love.

Who knew?

Actually, about 160 people, so far, know such details about their spiritual lives. They were the first participants in SoulPulse, a newly launched, ongoing study of spirituality in daily life.

It’s an “experiential” research survey inspired by pastor/author John Ortberg and conducted by a team led by Bradley Wright, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut and author of Christians Are Hate-Filled Hypocrites … and Other Lies You’ve Been Told.

Twice a day for two weeks, participants receive questions asking about their experiences of spirituality, their emotions, activities, and more at the moment the text messages arrive.

After 36 years of serving churches as a pastor and consultant, I came to a startling conclusion the other day.

Not startling to you, perhaps. I might be the last person to get the memo. But the conclusion drew me up short.

My conclusion: Religion shouldn’t be this hard.

THE WOMEN IN Talking Taboo: American Christian Women Get Frank About Faith aren’t just frank. They are courageous, clever, and wildly passionate.

This anthology, edited by Erin S. Lane and Enuma C. Okoro, asks 40 women under 40 to respond to the question, “What taboos remain in the church at the intersection of faith and gender?” The result is a collection of stories by women of faith (Baptist, Presbyterian, Mennonite, Catholic, Unitarian Universalist, and more) in a variety of roles (pastor, mother, writer, teacher, student, and more).

The women share times they have felt shamed, alienated, discouraged, or alone as women seeking a home in the church. From addressing domestic violence to lust to pregnancy to the role of a woman pastor’s body, the stories are raw in the way first-person narrative calls upon honesty and vulnerability to trump perfect prose or style.

Anthologies often stick to one structural extreme: Either they are rigid and theme-driven, or loose and nomadic. Talking Taboo follows the latter. Lane’s introduction promises no arc of narrative, no solid take-away message. The stories are here, she writes, because women are agreeing to “speak for ourselves.”

Cynthia Bourgeault explains how we can both seek social justice and do justice to our souls.