Spirituality

I recently picked up a fascinating book called Octavia's Brood co-edited by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown.

In a discussion about the book, Walidah Imarisha said, "All organizing is science fiction. What does a world without poverty look like? What does a world without prisons look like? What does a world with everyone having enough food and clothing look like? We don't know. It's science fiction, and it is as foreign to us as the Klingon homeworld."

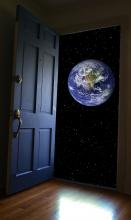

I had never heard of organizing being discussed in such a way, and it led me to reflect on the importance of envisioning and dreaming of the kind of society we fight to create. I also found myself reflecting on this statement in a different light: All organizing is also theological and spiritual. A simple explanation of this is that organizing and activism is faith in action.

Stereotypes of aging fall into four buckets. The first, the persistent image that is considered by many to be the norm, is that aging is something to be reviled and dreaded. At best, growing old is something best done out of sight and mind, ideally in a gated community and ultimately in some kind of institutional setting.

A more palatable position, the second bucket, acknowledges aging as a time of inevitable decline and detachment, but thinks this is not a bad thing. Known as “disengagement” theory by gerontologists, proponents of this bucket think of aging as a problem to be solved in order to keep elders as serene as possible as they transit the wasteland of old age.

The third bucket, activity theory, swings the pendulum to the extreme. As a result, a new generation of elders has been put on the run. To age “successfully,” one must be kept busy pursuing second or third careers, finding renewed purpose, reinventing ourselves, and otherwise proving that one can be productive and engaged to the end. An unfortunate side effect of activity theory is the adulation of youth and the legitimization of denial. Don’t like the idea of aging? Just don’t do it.

But there’s a fourth bucket, the one we have been exploring together since that memorable conversation on the stairwell. That is, aging as a spiritual path. In this vision of aging, growing older takes on added meaning as a life stage with value and purpose of its own. The key is embracing rather than rejecting or denying the shadow side of aging.

The universe is made up of 96 percent dark matter and energy, swirling with complexity — black holes, empty spaces, bad dreams, failed marriages, unknown territory, broken bowls and bruised shins and loneliness. And yet — look! — everything is still churning along. And in a way that can only be explained in the gut, these alarming dark things are perhaps the only things that have the tendency of bringing people together into community.

As Jean Vanier, founder of L’Arche writes, “In community life we discover our own deepest wound and learn to accept it. So our rebirth can begin. It is from this very wound that we are born.”

Her once boundless energy starts to fail by midday. She started radiation treatment on May 21, mainly in an effort to forestall the possible collapse of her spine, which would leave her helpless and in intractable pain.

“That sounds a little formidable to me,” she says.

“I was never much for suffering.”

She goes on, her words carefully chosen. “Am I grateful for this? Not exactly. But I’m not unhappy about it. And that’s very difficult for people to understand.”

Religious identity used to be “inherited.” “Cradle Catholic” is shorthand for born into the faith; within Judaism, the faith is passed through a Jewish mother to her children unless they grow up to proclaim a different religion.

But children don’t just inherit parents’ spirituality, says psychologist Lisa Miller in her new book, The Spiritual Child. She writes that the essential sense of a transcendent power in the world — one that will love, guide, and accept them and wrap them in a protective layer of self-worth -– has to be nurtured.

I have a confession to make. I have not always been very fair with the church, and for that I apologize.

In an effort to share my love and passion for my faith, I have picked and poked and criticized the church, and maybe that is a bit unfair. I have been a minister going on six years, and during that time, I have been the best and the worst that the church can offer.

I have a certain understanding of the way a church should operate, and when I do not see that being played out in the communities around me, it makes me upset: upset about the way God is presented, upset about the droves of people who will miss out on a life-changing relationship with God, and upset that I cannot change everything.

It's difficult for me as a young minister to slow down and be reflective in the face of impending decline and danger of closures for many of our congregations.

It's not easy being a minister today, and I guess it’s easier to take out my frustrations on the church instead looking for that 'silver lining.'

But I have a come to the conclusion that maybe all is not lost.

Nadia Bulkin, 27, the daughter of a Muslim father and a Christian mother, spends “zero time” thinking about God.

And she finds that among her friends — both guys and gals — many are just as spiritually disconnected.

Surveys have long shown women lead more active lives of faith than men, and that millennials are less interested than earlier generations. One in three now claim no religious identity.

What may be new is that more women, generation by generation, are moving in the direction of men — away from faith, religious commitment, even away from vaguely spiritual views like “a deep sense of wonder about the universe,” according to some surveys.

Michaela Bruzzese, 46, is a Mass-every-week Catholic, just like her mother, but she sees few of her Gen X peers in the pews.

It’s rare that a film can take all of these journeys and still tell a cohesive story. Sometimes, when we’re very lucky, a truly special film comes along that gets as close as possible to combining and distilling the infinite layers of the human experience. The Sojourners Internship Program is one of these truly special feats. It takes each facet of its characters’ journeys seriously, and allows each of them to explore those facets in their own unique ways.

Like most great stories, the setup of The Sojourners Internship Program is simple, but filled with the potential to go any number of directions: 10 individuals from different ethnic, economic, political and spiritual backgrounds are selected as interns for a social justice organization. They travel to Washington, D.C., to live in community and work together. But the community they live in is no ordinary community, and neither is the organization. The interns enter their house in Columbia Heights as strangers with hopes, ideals, doubts and a few preconceived notions. But they will leave forever changed.

THE LAST SUNDAY IN FEBRUARY is the first Sunday of Lent. We are asked to prepare for Lent by searching our souls and repenting of our misdeeds in order to walk with Jesus on his road to the cross. After writing the final reflections below, I felt unfinished. Repentance is easy to talk about but exceedingly hard to do. We justify and excuse our actions when we’ve hurt a friend or made a bad choice. It’s usually someone else’s fault anyhow—they started it!

The most striking example of human resistance to repentance I’ve ever read was in C.S. Lewis’ little book The Great Divorce. The “divorce” is the huge gap between heaven and hell. Hell is not fiery but filled with people who can’t get along with each other and keep moving further apart in the darkness. Eventually, a few make their way to a bus stop where they get a ride to the outskirts of heaven. There everyone is met by someone from their past they’d rather not meet, and who begs them to repent, make restitution, or whatever is necessary to enjoy a joyful eternity of loving relationships. For almost all of them, it’s not worth it. They fear losing the bit of ego they have left. They’d rather go back to hell than repent and be reconciled with someone they love to hate.

No wonder repenting is the first step to entering the kingdom of God!

It’s interesting how the word “grace” gets used a lot, even by those who don’t necessarily consider themselves religious. It’s a favorite name for a character that represents someone who is a gift to us — I’m thinking about Bruce’s girlfriend Grace in Bruce Almighty, or Eli’s reassuring encounter with a woman named Grace in the second season of the TV series Eli Stone.

You can probably cite many more examples of characters named Grace in different movies, television shows, and books.

We like to put flesh-and-blood on the notion that we are recipients of some great gift that arrives unexpectedly and is given freely. Someone or something that comes into our life and significantly changes it for the better in some ways.

But what is grace? Who is grace to us?

Faith is a journey, a Pilgrim’s Progress filled with mistakes, learning, humble interactions, and life-changing events. Here are a few things I would do differently if I could go back and start over:

1. I wouldn't worry about having the right answers.

There’s a misconception that the Bible is the Ultimate Answer Book and Christianity is a divine encyclopedia presenting the solutions to life’s biggest questions. In reality, the Christian faith is about a relationship with Christ instead of an academic collection of right or wrong doctrines.

Rather than wasting time, energy, and resources on superficial theological issues — I would focus more of getting to know Jesus. Never let a desire for “being right” obstruct your love for Christ.

Uber-atheist Sam Harris is getting all spiritual.

In his new book, “Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion,” the usually outspoken critic of religion describes how spirituality can and must be divorced from religion if the human mind is to reach its full potential.

“Our world is dangerously riven by religious doctrines that all educated people should condemn,” he writes in the book, but adds: “There is more to understanding the human condition than science and secular culture generally admit.”

The prescription, Harris holds, is Buddhist-based mindfulness meditation. A Stanford-trained neuroscientist, Harris is a long-time practitioner of Buddhist meditation. He said everyone can, through meditation, achieve a “shift in perspective” by moving beyond a sense of self to reach an enlightening sense of connectedness — a spirituality.

It was the beauty on the outside that drew me away.

Before social justice became trendy among evangelicals, people of all denominations, faiths, and philosophies had already been steadily working in the trenches without fanfare, caring for the least of these with a quiet strength.

Through seminary, I learned to grapple with justice being at the heart of the Christian Gospel — dignity, equality, and right to life for all — I marched out into the real world with zeal and vigor to champion the rights of the oppressed in the name of Jesus. However, I discovered the people who were doing this work often had no identification with Christianity, that those outside of church were behaving more Christian-ly than some inside.

I admired Nicholas Kristof, a self proclaimed nonreligious reporter, who tirelessly sheds light on humanitarian concerns.

I adored Malala, a Muslim, who stood up to the Taliban to bravely demand a right to education for girls.

I reflected on the justice heroes of recent history, people like Gandhi and countless other humanitarian workers who don’t claim the Christian faith for their own.

It disoriented me because for so long I believed it was only through Christ that one can walk in righteous paths; that without the Truth (which had been so narrowly summed up for me in John 3:16), everything was meaningless. I didn’t have an interpretive lens to categorize beauty that existed outside of the vessel I was told contained the only beauty to be found: the evangelical Christian church.

MARQUETTA L. GOODWINE, a computer scientist, mathematician, and community organizer, grew up on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. On July 2, 2000, Goodwine was “enstooled,” in a traditional African ceremony, as “Queen Quet,” political and spiritual leader of the Gullah/Geechee Nation that extends from coastal North Carolina to Jacksonville, Fla.

“A lot of people don’t know that we exist,” she told Sojourners. “People are unaware that there is a subgroup of the African-American community that’s an ethnic group unto itself, with nationhood status for itself.”

Queen Quet, and the Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition she founded, are actively engaged in battling environmental racism and climate change. As a cultural leader of an Indigenous community, she works to preserve her people’s heritage in the land and stop corporate encroachment. As a spiritual leader of a people who practice a unique form of faith that adheres to Christian doctrine while being distinctly African, she nurtures her people’s tradition of communal prayer, song, and dance, as well as their connection to Praise Houses, the small places of worship built on plantations during slavery.

Sojourners contributing writer Onleilove Alston, lead organizer in Brooklyn for Faith in New York, a member of the PICO National Network, sat down with Queen Quet on St. Helena Island in Beaufort County, South Carolina, to learn more about the Gullah/Geechee people, their spirit, and their struggle for justice. —The Editors

THE GULLAH/GEECHEE PEOPLE are the descendants of African people that were enslaved on the Sea Islands. We are descendants of Igbo, Yoruba, Mende, Mandinka, Malinke, Gola, Ife, and other ethnic groups from the Windward Coast of Africa, as well as Angola and Madagascar.

We also have Indigenous American ancestry from the Cusabo, Yamasee, Cree, and Edistow, the original inhabitants of the land now held in the Gullah/Geechee Nation. A socio-anthropologist segregated us at one point, saying that Gullahs are on the South Carolina Sea Islands and Geechees are on the Georgia Sea Islands, but there is no difference between us. We are one people.

In 1999, I became the first Gullah/Geechee in history to speak before the United Nations. Now I am a member of the International Human Rights Association of American Minorities, an NGO with U.N. consultative status, and the International Human Rights Council (a coalition of human rights scholars and activists that works on key human rights issues).

It’s easy for the faith of children to go unnoticed. But here are four spiritual things kids do better than adults:

They Ask Questions:

Nobody asks more — or better — questions than children. “Who?” “What?” “Where?” “When?” and “Why?” are expressions patented by kids everywhere. They’re obnoxiously curious and want to know everything about everything.

They aren’t afraid to ask the most difficult and messy questions. Too often we mistake spiritual maturity for certainty, and lose our thirst for discovery. Kids remind us how to approach God — truthfully, stubbornly, inquisitively, and tirelessly.