restorative justice

One of my favorite passages in the Bible is from in Isaiah 61:1: “The spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me; he has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and release to the prisoners.” Christians will be familiar with this passage as Jesus quotes it when he stands up to read in the synagogue during the early days of his ministry (Luke 4). It’s a passage that gives me some hope for Christianity, since the central character of our religion believed that even the worst-of-the-worst deserve forgiveness.

Taking the next steps in constructing a more just church and society.

ONCE A MONTH, 30 mothers and grandmothers gather at the Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation in Chicago. The women share a meal before coming together in a circle. Facing each other in their chairs, they begin to share stories of painful loss.

Sister Donna Liette, who coordinates the organization’s Family Forward Program, created this space 10 years ago for women who have lost children and grandchildren to gun violence or incarceration. Gun violence has been a devastating reality in the city for decades. In 2020 alone, the Cook County Medical Examiner reported 875 gun-related homicides. And while incarceration rates have declined in recent years, Illinois had approximately 38,000 incarcerated individuals in 2020, according to the Henry Frank Guggenheim Foundation.

Liette says she keeps in touch with around 80 women through the program, many of whom attend the monthly gathering. Judy Fields is one of them. Three of her grandchildren have been killed by gun violence in the Back of the Yards neighborhood.

“I first met Sister Donna four years ago, and we became instant friends,” Fields said. “I don’t have anybody to talk to, and she fills that void. She looks after me—she knows how to listen.”

IN 1974, TWO teenagers went on a vandalism spree in the quiet community of Elmira, Ontario. They slashed car tires, broke store windows, and destroyed a garden gazebo, racking up about $3,000 worth of damage. The pair faced jail time for malicious vandalism. Instead, their parole officer, Mark Yanzi, who was also part of Mennonite Central Committee in Canada, asked the presiding judge if the youths could meet their victims face to face. This, they said, would allow the offenders to apologize directly and pay for damages. The judge agreed—setting legal precedent in Canada.

Though Indigenous and First Nations communities have a long history of similar conflict resolution practices, the Elmira case is seen as a moment when formalized restorative justice models, known at the time as victim-offender reconciliation programs (VORP), entered the Canadian criminal legal system. And Mennonite Christians were integral from the beginning.

In a 1989 handbook, VORP Organizing: A foundation in the church, Ron Claassen, Howard Zehr, and Duane Ruth-Heffelbower further developed the concept of VORP as a program that could work in cooperation with the judicial system but embodied “different assumptions about crime and punishment.”

“True justice requires that things be made right between the one offended and the one who has done the offending. It embodies a concept of restoration—of victim as well as offender. This also implies personal accountability on the part of the offender, who is encouraged to acknowledge his or her responsibility for the harm, participate in deciding what needs to be done, and to take steps to make amends,” they wrote.

A FEW YEARS AGO, Ched Myers and I discovered this graffiti in my old suburban neighborhood in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, scrawled across a fence just a block from where I grew up:

“... as long as the sun shines,

as long as the waters flow downhill,

and as long as the grass grows green ...”

It is a venerable phrase from the Two Row Wampum of 1613, an agreement between the Five Nations of the Iroquois and representatives of the Dutch government in what is now upstate New York, which affirmed principles of Indigenous self-determination, rights, and jurisdiction. The phrase has been reiterated in most subsequent treaties between European settlers and Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Sixty miles due north of my old neighborhood is Opwashemoe Chakatinaw (named Stoney Knoll by settlers), nestled between the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers. A spiritual center for the Young Chippewayans, it was part of Reserve 107, assigned to this Cree tribe in 1876 under Treaty 6.

FOR ABOUT TWO decades I was part of a small, unaffiliated fundamentalist religious community in South Carolina. There I learned that Jesus’ condemnation of religious hypocrisy was a warning to adhere tightly to the church’s long list of superficial rules for holy conduct. It was a holiness defined more by rule compliance than goodness of heart.

Later, in college, I learned that Jesus was making an institutional critique more than an individual one in those biblical passages. He was in fact condemning a devotion to rigid rules that emphasized appearance over substance and venerating law while neglecting the soul.

Such beliefs are an apt metaphor for the fundamental defect in a near-century of U.S. police reform efforts. Most have ignored the heart and soul of our policing and carceral institutions; they have instead tinkered with these institutions’ appearances. Many of these reforms likely reduced some harms of U.S. policing. Yet, they have left largely in place the ideas and practices that taint the heart of American policing: Police techniques—even those blessed by law—maintain an anti-Black, gendered, heteronormative, and ableist status quo. As Christian faith teaches, mere adherence to rules is not holiness. As we learn by examining the limitations of police reform, reduction of harm is not justice.

TWO WHITE TEENAGERS were recently convicted of spraying racist graffiti on a historic black school in northern Virginia. Their somewhat unusual sentence: Read from a list of 35 books, one a month for a year, and submit a report on all 12 to their parole officers. The booklist included Cry the Beloved Country, by Alan Paton,To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou, Night, by Elie Wiesel, and other classics.

The remarkable feature of this sentence was how it clashed conceptually with the customary default question that suffuses our judicial system: How long a prison sentence does the crime deserve?

A strange mathematics is at work in our criminal justice system: For every crime, a matching time in prison. Translating the crime of racist graffiti into reading books that might reform the minds of two teenagers makes a certain rational match with the crime. Putting them in prison for five years is no match at all.

EVERY DAY FOR A YEAR, Marcus awoke in a locked room in a Wisconsin youth prison.

“You wake up every day hoping it’s a dream, and it’s not,” said Marcus, who at 17 was sent to the Lincoln Hills boy’s detention center for sexual misconduct. “Four walls, a desk, and a cot.”

He said guards in that lockup often told boys, “You’ll be back.” But Marcus—who spoke on condition that he not be identified by his full name—not only swears that’s not going to happen to him, he’s working to keep others from having the same experience.

Despite years of reform efforts, thousands of teens still wake up in large, secure, prison-like facilities such as Lincoln Hills, many of them for nonviolent offenses. Marcus is one of a growing number of voices arguing that such places should be shut down for good.

“It’s clear that youth prisons are not places of redemption and hope,” said Liane Rozzell, a senior policy associate at the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The foundation has led a nationwide push to shutter juvenile incarceration facilities, which have failed to reduce youth crime, and replace them with effective alternatives that keep kids in their communities, are less expensive, and drive down the juvenile crime rate. “There’s a clear lane for faith-based organizations and people to grasp that real care for young people means we will not be putting them in situations that traumatize them, cut off their opportunities, and lead them to essentially be thrown away,” Rozzell said. These institutions fail the duty to provide for the “basic human dignity” of youth, she added, violating the principles not only of Christianity but of many other faiths.

“The Church has both the unique ability and unparalleled capacity to confront the staggering crisis of crime and incarceration in America,” the declaration reads, “and to respond with restorative solutions for communities, victims, and individuals responsible for crime.”

People of color in the United States, particularly young black men, are burdened with a presumption of guilt and dangerousness. Some version of what happened to me has been unfairly experienced by hundreds of thousands of black and brown people throughout this country. As a consequence of our nation’s historical failure to address the legacy of racial inequality, the presumption of guilt and the racial narrative that created it have significantly shaped every institution in American society, especially our criminal justice system.

America’s justice system is broken.

Our jails are overflowing, people are receiving life sentences for minor crimes under three strikes laws, racial disparities leave minority populations disproportionately represented in the incarcerated population, and we’re so obsessed with killing that we’re now using untested concoctions of drugs that recently took a condemned inmate more than 20 minutes to finally die.

Our system isn’t working.

It might surprise you however, to understand how we arrived at such a broken justice system.

We got here because of poor theology.

The difficulty of restorative justice, is that some things simply can’t be restored.

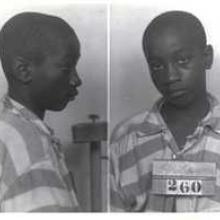

Certainly, not 14-year-old George Stinney. He’s been dead almost 70 years.

We can however, restore his name — and sometimes, that’s all restorative justice can do. Restorative justice works to make whole what has been unjustly lost and reassemble that which has been unjustly broken, to the greatest degree humanly possible. While we can’t restore 14-year-old George to life, we can both restore his name and work to restore the community responsible for his death.

Often we forget that restorative justice isn’t just about restoring the one who was wronged; the one who committed the wrong is also need of restoration. In this case, the latter is the state of South Carolina.

Next to biblical nativity stories, How the Grinch Stole Christmas by Dr. Seuss is one of my favorite seasonal tales. We read it as a family every Christmas Eve.

While we typically view this vintage Dr. Seuss yarn as a reminder that there is more to Christmas than its trappings, it offers something unexpected too. It shares an example of restorative justice at work.

When I got off the plane at O’Hare Airport in Chicago on my way home to Boston on April 15, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Televisions blaring everywhere showed my beloved city at her premier event of the year, the Boston Marathon. Everyone knows the rest of the story.

“Is this for real? How can this be?” I asked, unable at first to face the reality of what had occurred. Feelings of fear and anger followed quickly on the heels of the denial.

Leaders responded quickly: the mayor, the governor, the president. “Any responsible individuals, any responsible groups will feel the full weight of justice,” promised President Barack Obama.

What is justice? Vengeful words immediately spewed from talk shows and bloggers’ keyboards. “We must catch them alive and make them suffer as much as possible. That will pay them back for what they did,” spewed those who equate justice with revenge.

Of course, violence begets more violence. Gandhi put it succinctly: “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” Paul exhorted the Romans, “Repay no one evil for evil, but take thought for what is noble in the sight of all. . . Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to God, for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay,’ says the Lord. (Romans 12:17,19.)”