The difficulty of restorative justice, is that some things simply can’t be restored.

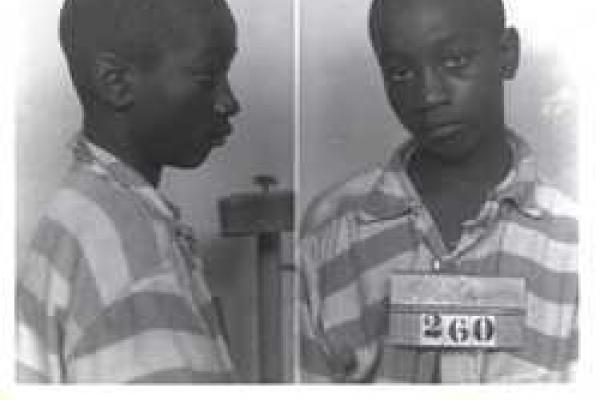

Certainly, not 14-year-old George Stinney. He’s been dead almost 70 years.

We can however, restore his name — and sometimes, that’s all restorative justice can do. Restorative justice works to make whole what has been unjustly lost and reassemble that which has been unjustly broken, to the greatest degree humanly possible. While we can’t restore 14-year-old George to life, we can both restore his name and work to restore the community responsible for his death.

Often we forget that restorative justice isn’t just about restoring the one who was wronged; the one who committed the wrong is also need of restoration. In this case, the latter is the state of South Carolina.

Read the Full Article