medicine

Abdul El-Sayed, a Michigan-born American of Egyptian descent who, last year, very nearly became the first Muslim governor in U.S. history. Abdul is a professor and medical doctor turned politician and civil servant, who has a fantastic new podcast with on public health called America Dissected. Additionally, his new book, Healing Politics, will be out on May 5, 2020 and is now available for pre-order.

Sa’Ra Skipper says that it was at her lowest point, staring death in the face every day, that she realized God’s presence in her life. Skipper was away from home at college and had unexpectedly lost coverage for the daily insulin she needs to treat her Type 1 diabetes. The cost of that insulin had climbed to the point where the monthly cost of her medicine and supplies was over $1,000. Skipper didn’t have that kind of money.

Nystrom started calling out the pharma corporations by name, and the U.S. politicians that allow the companies free rein to charge prices that are unthinkable in other nations. “Let’s be honest: the companies and the U.S. government are allowing people to die,” she says. “I wasn’t going to sugar coat that message.”

Tobeka Daki became one of 10 million people who die each year because they cannot afford the cost of medicines. Most medicines are inexpensive to make, and virtually all were discovered thanks to government investments. So, it is no exaggeration to say that the worldwide network of medicine monopolies, which give unchecked power to charge virtually any price on life-essential goods, were the cause of most of these deaths.

Dr. Denis Mukwege, who has just received the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in the Democratic Republic of Congo, shows us one example of what global Pentecostalism can look like. Mukwege is sharing the award with Nadia Murad of Iraq for their efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict.

Mukwege’s Panzi Hospital, located in Bukavu at the heart of the conflict-ridden South Kivu province, treated over 50,000 survivors of sexual violence during the last 20 years. Mukwege has also repeatedly criticized the Congolese government. In 2012, he was almost assassinated and his family was held at gunpoint.

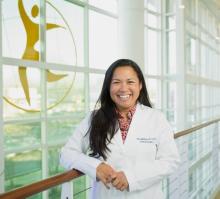

Nia Zalamea is a board-certified general surgeon. After five years in a traditional medical practice in rural Virginia, she joined the Church Health Center, an organization in Memphis, Tenn., that seeks to reclaim the biblical commitment to care for our bodies, minds, and spirit. She is one of two general surgeons in the U.S. who does full-time charitable work.

1. Why did you leave traditional medical practice? I went into medicine to serve; it was the one craft and skillset I could offer to an individual in front of me. But after five years, I found out that I wasn’t actually living my mission; I had put five people into bankruptcy. What I saw in rural America was that even one operation could completely derail not just one generation but multiple generations. Not just in terms of economics, but in terms of social capital, education, and everything we know that affects health and medical care.

2. What exactly does the Church Health Center do? The Church Health Center is a medical wellness home for the underserved, the uninsured, and the underinsured of Memphis. We provide surgery on a sliding scale; if someone can’t afford the surgery, it gets written off. The hospital supports the surgery in not charging the hospital fee, which is a huge chunk of the cost. So it’s not free, but the out-of-pocket cost for the patient is extremely low. We just make it affordable.

3. What are some of the barriers that prevent your patients from having access to health care? We have ongoing workshops during open enrollment to get people on to Affordable Care Act plans, but what is deemed “affordable” is not always affordable; the majority of my patients are 150 to 200 percent below the poverty line. Another barrier is access: Just because you have an insurance card doesn’t mean the doctor will see you. And this is where a lot of the injustice lies; many doctors’ offices and businesses have closed their doors to new Medicaid patients. Finally, the Affordable Care Act doesn’t cover everyone; my patients include undocumented immigrants, refugees, and patients from other countries whose children are being treated nearby at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

EARLY IN Being Mortal, surgeon Atul Gawande tells the story of Joseph Lazaroff, a patient with incurable prostate cancer. His medical team pursued multiple treatments, including emergency radiation and surgery, but Lazaroff ultimately died. What most struck Gawande later was that he and the team avoided talking honestly about Lazaroff’s choices—even when they knew he couldn’t be cured.

“We could never bring ourselves to discuss the larger truth about his condition or the ultimate limits of our capabilities, let alone what might matter most to him as he neared the end of his life,” Gawande writes. “The chances that he could return to anything like the life he had even a few weeks earlier were zero. But admitting this and helping him cope with it seemed beyond us.”

Why is that? For one, Gawande’s medical training didn’t prepare him for dealing with frailty, aging, or dying, he writes. He and his peers were taught to “fix,” to heal people with expertise, tools, and tests. Like most doctors, he approached his patients’ challenges as medical problems to solve, whether they were the accumulations of old age or terminal illness.

TWO OF MY greatest teachers were Latin American men, both ordained as Catholic priests. One, Archbishop Oscar Romero, was assassinated in 1980. I never met him, being a 20-year-old American who’d never set foot in El Salvador or anywhere else in Latin America. But Romero made me, a lapsed Catholic, wonder why his views—our views, if Christian social teaching means anything at all—would be viewed with murderous hostility by the Salvadoran elite. After all, it was all right there in the Book. Wasn’t it?

The truth was, I didn’t know. Was it worth looking at books about these matters? That’s what we believed in medical school: Look it up! So Romero led me to the second of these teachers who, I’m happy to say, is alive and well and living (mostly) in Lima, Peru. Gustavo Gutiérrez, a diminutive and humble Dominican priest and a great friend of Romero’s, taught me through his books, from The Power of the Poor in History toWe Drink from our Own Wells, and later through his friendship and his almost mystical (to me, in any case) optimism.

Over the course of my 20s, the slender, frayed thread of my own faith, which I had believed cut, slowly came back into view. There was a filament a bit stronger than imagined, made visible in part by my Haitian hosts and patients and friends, and in part by Catholic social activists working against poverty in settings as different as tough neighborhoods in Boston, the farms of North Carolina, and the slums of Lima.

Some were nuns or priests, some were engaged laity, from many professions. Most were people living in and struggling against their own and others’ poverty. Their activism taught me a lot about a space in the Catholic Church I’d not seen clearly before, and about the promise of long-term engagement in the monumental struggle against poverty and discrimination in all its forms. That includes gender inequality, no stranger to the institution. Most of the most inspiring activists were women.

This morning, Madu walked the one kilometer path from his village to my house. He is married to Sirima and they have two children: four-year-old Sira, who they call Bonnie, and two-year-old Musa, who they call Papa. He told me that Papa had burned his hand and wrist in the morning cooking fire.

Maybe the path to civility and peace can be found somewhere along the path from my house to Madu’s village.

“Do you have any medicine for a burn?” he asked.

There is a hospital in our small town on the southwestern edge of Mali, but its small staff of doctors serve a large population of people without the use of technology, electricity, or even running water. Many times people come to me for help and healing before they go to the hospital because I have free first aid supplies, a generator, and a deep water well. I consulted my ragged copy of Where There Is No Doctor and turned to the section on the treatment of burns.

Every so often I hear the insinuation that women (like me) who advocate for "normal" childbirth are inordinately self-focused (even selfish) and that women who are dissatisfied with the treatment they’ve received in hospitals during labor are “uncheerful” and, possibly — according to the women in controversial pastor Douglas Wilson’s life — confused theologically.

Don’t get me wrong: Ricki Lake’s memoir, at least as it concerns childbirth, definitely looks at the birth experience as if it is all about her. But while there’s no question that medical advances (and, yes, c-sections!) save lives, it’s also hard to contest the fact that medical interventions occur at rates that are simply unjustified.

September 3 (Labor Day) launched “Empowered Birth Awareness Week,” which, sponsored by ImprovingBirth.org, aims to raise people’s consciousness concerning the notion of “evidence-based maternity care,” the less than radical notion that what happens during birth (ie, continuous fetal monitoring, mandatory IVs, NPO rules that prohibit eating and drinking) should be medically indicated, not routine, and supported by sound medical research.

Biblical literalism, and the corresponding idea of the inerrancy of scripture, has been bumping up against the sciences for a long time.

Way back in the Renaissance, the church insisted that the Bible taught that the sun revolved around the earth, and charged Galileo with heresy for claiming otherwise. Today, the debate between the Bible and natural science continues, most notably in the evolution/creation debate.

While discussions of religion and science usually revolve around conflicts with natural science, I'd like to propose that the place we really should be placing our attention is the relationship between faith and the social sciences.

As our understanding of all science grows, it becomes harder and harder to maintain the position of biblical literalism without seeming absurd.

Maybe we haven't all heard the thunder clap yet, but the lightning bolt struck a while ago. We are going to have to adjust our reading of the Bible to coincide with a modern scientific understanding of the universe. In broad strokes, that shift has already happened.

A new survey of medical patients found that prayer — with their physician — is for many an important part of the treatment process.

According to American Medical News:

About two-thirds of patients believe doctors should know about their spiritual beliefs, said a survey of nearly 500 adults from Florida, North Carolina and Vermont in the January 2003 Journal of General Internal Medicine.

One in five patients likes the idea of praying with the doctor during a routine office visit, while nearly 30 percent want to do so during a hospital stay, the study found. Half of patients would want to pray with the doctor in a near-death scenario.

About 75 percent of physicians say patients sometimes or often mention spiritual issues such as God, prayer, meditation or the Bible, said an April 9, 2007, article in Archives of Internal Medicine.

The question of whether it is appropriate for doctors to pray with patients was addressed in late May at a three-day conference organized by the University of Chicago Program on Medicine and Religion.

G. Richard Holt, MD, MPH, a recently retired otolaryngologist, gave a presentation reviewing his perspective as a head-and-neck surgeon.

During his 40-year career, Dr. Holt received about one or two prayer requests a month. He made it his practice to remain silent while the patient, a family member or religious leader prayed aloud. But Dr. Holt drew the line at initiating or leading prayer.

Read the article in its entirely HERE.

"I think it is a spiritual task to struggle with questions such as what and who we place at the center of our economy"

The U.S. should put publicly funded medicines in reach of the world's poor.

When our ideas about nature come primarily from Sierra Club calendars or selected snippets from Thoreau, an east coast earthquake and monster hurricane (in the same week) are powerful wake-up calls.

We modern urban dwellers and suburbanites like our nature contained and manageable: a nice hike in the woods; a pretty sunset on the drive home; a lush, green lawn (chemically-induced, alas)

Sometimes we like nature so much we decide to worship it -- or to make it the medium for our worship of God or the "higher power" we think might be up there, out there, presiding over it all. We've been wounded by organized religion, perhaps, disgusted by its hierarchies and hypocrisies. "I can worship God on a mountaintop," we decide. (Or -- conveniently, happily -- on the golf course).