farming

BARBARA BROWN TAYLOR was supposed to be a poet or a short story writer. She accrued a respectable stack of rejection letters to show she tried. Instead, she became an Episcopal priest. One day, someone asked for a transcript of her sermon, and Taylor realized she had published her first story.

She went on to publish several collections of sermons or what she likes to call “spiritual meditations.” Ranked by Baylor University as “one of the 12 most effective preachers in the English-speaking world,” Taylor left parish ministry in 1997 and taught religion from 1998 until her retirement in 2017. She is the author of 15 books, including Leaving Church, An Altar in the World, Learning to Walk in the Dark, Holy Envy, and Always a Guest. She now devotes most of her attention to the farm she shares with her husband, Ed Taylor, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in north Georgia, where they have lived since 1992. But she still writes. She is working on Coming Down to Earth, a book about reverence, and she shares short reflections on the beauty of life on her email newsletter with the same title.

Sojourners associate editor Josina Guess lives on a small farm in Georgia, not far from Taylor, and the two spoke in January over Zoom about caring for animals, finding balance, loving neighbors, and the power of resurrection.

A LITTLE OVER a year ago, members of Ann Arbor’s Zion Lutheran Church in Michigan stood on an L-shaped plot bordering their church garden. Those 800 square feet of ordinary lawn were on the cusp of transformation, about to become the source of Zion’s own Communion bread.

While Christians traditionally think of Communion as transforming partakers during the church service, project leader Betsy King-McDonald wanted to explore the life-giving properties of the Eucharist at an earlier stage — starting in the soil.

“How can we foster life in all the choices we make to the table?” she asked. This question led King-McDonald, a doctoral student at Western Theological Seminary, to partner with Zion Lutheran in growing heirloom wheat for their Communion bread.

In the slanting October light, members rototilled the church lawn. Youth lugged wheelbarrows of wood chips from the parking lot. Then Joet Reoma, a local master gardener and board member of Project Grow, a local nonprofit that facilitates community gardens, directed participants in a complex ritual that resembled making a dirt lasagna. The “lasagna” was not for humans, but for the microbial life in the recently turned soil.

In a trademark black cap with tag still attached, his name scrawled on the tag in bold black marker, Reoma called out basic permaculture steps: First, spread fresh wood chips, high in nitrogen but slow to decompose. Next, add a layer of vermicompost — worms with their eggs and castings, ready to break down the organic matter. Sprinkle cornmeal on top, energizing the worms and kick-starting mycelial growth in the wood chips. Finally, two more layers; one of decomposed wood chips and one of compost. Now, the soil community was ready to receive the wheat seeds.

This elaborate process of feeding the soil that would nurture the church’s Communion wheat expressed a deep eucharistic truth — the process and the produce hold the power of life.

Rarely do churches interrogate how liturgical elements support life all along the way — from soil to markets to table. As King-McDonald found, tending to the process clears a path for deeper place-based Christian discipleship.

After poking neat rows of holes in the living soil, Zion Lutheran’s team dropped wheat kernels into the darkness, covered them, and spread a layer of straw over it all.

IN THE VAST and often overlooked landscapes of rural America, families face unique challenges. One critical issue stands out: the child care crisis. Our family-run produce farm in Ohio has been in production for 28 years. With three generations working to create a viable business to support our growing family, we know something about the need for child care in rural areas. The 2023 U.S. Farm Bill presents a crucial opportunity to address this pressing issue and foster early childhood development in rural communities.

The child care crisis is not unique to rural America, but rural Americans are more impacted by the lack of access to licensed child care. For example, 59 percent of rural communities are “child care deserts” compared to 56 percent of urban and 44 percent of suburban communities, according to a 2018 report by the Center for American Progress. In rural communities, families often struggle to find accessible, affordable, and high-quality options. Remote locations, limited infrastructure, and lack of providers exacerbate the challenges. The crisis not only hampers parents’ ability to work but also impedes the economic imperative to attract younger farm families to replace aging American farmers — more than half of whom are within a decade of retirement. The price of health insurance and the lack of child care make full-time farming out of reach for many younger Americans.

Healing from religious harm: Why compassionate community is part of the journey.

“DO YOU MAKE any money from it?” a visitor asked as we walked behind my house, where goats, chickens, fruits, and vegetables grow among the weeds. I shook my head and laughed.

We entered the garden where my 74-year-old father knelt, breaking up soil with an old cultivating fork. He was planting spindly tomato plants I had started from seed and almost abandoned.

We don’t make money from it, but the garden is the place where my father cultivates joy. When I was a child, he poured water on rows of collards to wash away stressful days working for a Washington, D.C., nonprofit. Gardening restores his soul. These days, Dad splits his time between my parents’ home in Ohio and my home in rural Georgia, planting gardens in both places.

We don’t weigh the bushels of okra, cantaloupe, peppers, watermelon, and beans to see if they equal or surpass expenditures of time or money spent on Dad’s trips down South. Some work can’t be measured in dollars.

How the “welfare state” is designed to subsidize affluence rather than fight poverty.

I NODDED ALONG with everything in the holistic permaculture course until day four, when things went off the rails. My family and I were at a farm in Bolivia, volunteering and learning about land design, groundwater recharging, alternative energy technologies, and returning fertility to the earth. Day four’s topic was community-building, which sounded innocuous enough.

Our host and instructor was a man from New Zealand who has farmed two acres in a remote Bolivian valley for nearly a decade. He talked about the importance of local decision-making, how focusing on global problems over which we have little influence can leave us feeling disempowered. Human-induced climate change, he added, is another story the oligarchs at the top are telling to stoke our fears and get us to surrender our freedoms. That and the pandemic.

Our host’s views are extreme. But he is among a growing group of back-to-the-land conservatives who don’t fit my categories. He disbelieves mainstream climate science, yet he is installing solar ovens, composting toilets, and bioconstructed buildings on his property. He scoffs at “wokeism,” which he sees as another form of top-down control, yet he deeply respects the local Indigenous community and attends the Quechua-only neighborhood meetings with surrounding farmers.

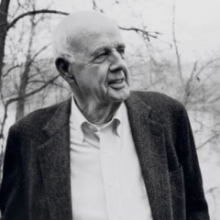

CLARENCE L. JORDAN died on Oct. 29, 1969, at 57 years old. The radical Southerner who dedicated his life to farming, sharing the gospel, and imploring his neighbors to actually follow Jesus is not widely remembered. Jordan died as simply as he lived — buried in a wooden box used to ship coffins, in an unmarked grave, and wearing his overalls. In early 2020, a little more than 50 years after Jordan (pronounced “Jurden”) died, I came across his work and was enamored. I began reading anything from or about him I could find. Jordan’s Georgia roots and love for the South mirrored my own. His charm and cutting humor were irresistible. Most appealing was Jordan’s stubborn commitment to radically following Christ, which led him to reject and rebuke the practices of racism, capitalism, and militarism in the U.S.

On the podcast Pass the Mic, writer Danté Stewart put a name to what I found in Jordan. “The reason why white [siblings] are struggling in this moment is because most of their models have been violent white supremacists,” Stewart said. “White [siblings], they don’t have models of liberation and love, so therefore they’re struggling in this moment.” Clarence Jordan was a “model of love and liberation” that we can learn from now. The dehumanizing forces of racial capitalism and militarism are no weaker in the U.S. today than in his lifetime, and many white Christians are avid proponents of both. Jordan’s resistance and radical theology did not die with him; instead, they can evolve and grow with the times. We should engage Jordan without idolizing him and advance his core commitments with a critical eye, honestly appropriating them for our modern struggles.

Farmworkers in Palm Beach, Fla. are set to march five miles in protest of Wendy’s treatment of farmworkers, and their protest has received a blessing from the Archbishop Thomas Wenski.

THE COVID-19 CRISIS has intensified food insecurity and hunger globally and exposed the failings of a profit-driven, industrialized agriculture and food system.

In August, an alliance of more than 500 African faith leaders and smallholder farmers delivered a strong message to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation: “The Gates Foundation’s support for the expansion of intensive industrial scale agriculture is deepening the humanitarian crisis.”

Faith communities and farmers want the Gates Foundation to stop funding the so-called “green revolution technologies” through the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). African faith leaders are witnessing the negative impact of industrialized farming to the land and the well-being of their communities. They are calling for a shift to sustainable and agroecological farming that works in local contexts for people and does not harm the land.

“HAY MÁS TIEMPO que vida” was my dad’s refrain every time I was stressed and weary. “There is more time than life.” His simple words had profound implications.

Being present to life is difficult. Life demands that we “rise and grind.” Reward comes to those who make the most of the time they’ve been given. Time is money. Time is a commodity we trade. The promise of life is the goal of all this grinding—or retirement, if we are privileged.

During the pandemic, I’ve pushed against beliefs that commodify time. I’ve cooked the foods that nourished my ancestors: tamales verdes, atole de tamarindo, and nopalitos. My senses have been awakened through mixing the nixtamalized corn flour with water and fat until it reached the right texture, peeling and deseeding each tamarind pod, cutting the nopal (cactus) and cooking it with a few tomatillo husks to remove the slime.

The preparation of these foods forces me to notice the rough spots on the cacti where thorns still make their home, to smell the acid scent of tamarind in the pulp clinging to my fingers; it invites me to play with the unruly dough that believes its place is on top of the corn husk and not inside. If death shows up in separation, life sprouts in connection.

This younger crop of Catholic Workers is unquestionably interested in activism, but the issues they address are different from those of their predecessors.

IN HIS ESSAY “The Land Ethic,” environmentalist Aldo Leopold tells a story from The Odyssey in which Odysseus, upon returning to Troy, hangs a dozen slave girls for misbehaving in his absence. The act, Leopold writes, was not one of ethics but of property: “The ethical structure of that day ... had not yet been extended to human chattels.” Leopold uses this as an example of how our ethical structure has expanded over history. This expansion of the moral circle is a common thread in history, encompassing, slowly, people and things that were once outside moral consideration.

WE LURCH FROM ecological crisis to crisis, all of them real: So far this year we’ve seen the sickening collapse of much of the Pacific’s coral in a 10-month blitz of hot ocean water; we’ve watched a city of 90,000 evacuated ahead of a forest fire so big it was creating its own weather; and we’ve witnessed the earliest onset of widespread Arctic melting ever recorded. And so on.

All of these need urgent responses—the fire company has to report for duty. So it’s been sweet to see activists doing civil disobedience on an unprecedented scale around the world and increasingly putting the fossil fuel industry on the defensive. We’ve got to turn the tide soon.

But “soon” and “urgent” and “emergency” are words that can blind us as well—keep us from seeing the deep roots of problems and solutions. So it is a very good thing that we have some folks who don’t scare easily. I’m thinking in particular of Wes Jackson and Wendell Berry, who keep patiently pushing the most deeply (and literally) rooted piece of legislation I know of, the 50-year Farm Bill.

The Kansas geneticist and farmer, and the Kentucky writer and farmer, begin with the premise that roots are important. Our industrial agriculture has plowed up the perennial crops that once covered the continent (and the planet) and replaced them with high-yielding annuals. All that wheat and corn feed us cheaply—and lead to dead, eroding soils that, among other things, can’t soak up much in the way of carbon. So Jackson, at his Land Institute, has spent the last decades crossing annual and perennial crops. The goal is nothing less than grains you don’t need to replant every year—grains that will grow deep, tangled roots into the prairie soil, feeding us and restoring a desperately needed balance.

The Berry family has lived in these parts for nine generations. While pursuing a prolific writing career, Berry never stopped caring for the land of his ancestors. Now, the 81-year-old writer wants to pass on his family’s farming legacy to a new generation. He decided against teaming up with a large university agricultural program, and instead selected a small Catholic liberal arts college about an hour’s drive from Louisville, run by the Dominican Sisters of Peace.

THE PLOW. Today it is a nostalgic symbol of a nearly forgotten agrarian past. This farm tool evokes scenes of wholesome farmers who, by the sweat of their brow, churn under dark, rich soil with help from a friendly beast of burden. After scattering seeds of wheat and the blessing of good rain, those fields will become amber waves of grain. The family will celebrate another good harvest. The bread will sustain them through another winter until fields can be planted again.

Scraaatch. Wait a minute! Wes Jackson, geneticist, farmer, and author, wants to interrupt this pastoral vision. In fact, he would interpret it quite differently. He might describe a scene of environmental carnage in which an unwitting population slowly sows the seeds of our own destruction by slipping the plow blade under the living skin of a quickly failing planet. “The plow has destroyed more options for future generations than the sword,” Jackson states bluntly.

Nearly half of the world’s soil suitable for growing crops has disappeared since humans started tilling and planting. Today, up to 70 percent of our caloric intake comes from staple cereal crops planted in large-scale annual monocultures. A study by the National Academy of Sciences estimates that we are losing soil 10 times faster than we can replace it. While Jackson acknowledges that over-reliance on fossil fuels is a crucial issue, he argues that “soil is more important than oil and just as nonrenewable.”

In addition to the danger of soil loss, agricultural production “provides the lion’s share of greenhouse-gas emissions from the food system, releasing up to 86 percent of all food-related anthropogenic greenhouse-gas emissions.” The global food production system—from planting to packaging—contributes about one-third of all greenhouse-gas emissions, though this topic was not part of the recent climate negotiations in Paris.

While practices of low-till and no-till annual crops help reduce erosion and increase the availability of arable land as a carbon sink, these half-measures aren’t effective enough, according to Jackson. What he proposes is nothing less than a wholescale rethinking of the fundamental tenets of agriculture.

The day after Easter, it snowed. I was carrying in my last buckets of sap before leaving for Portland and was not surprised by the flurries, but they still stymied my expectations of warmer weather. The equinox had passed several weeks before, and while the start of spring had been marked on the calendar, it was (is) dragging its feet in coming.

Who has known the mind of God or even a good 7-day weather forecast?

We see and know in part. Certainty has never been the steady state of the human condition. Our lives are stretched with the awareness that clarity, at its best, comes with a smudge.

The experience of knowing we do not know can be felt in different ways. One is confusion, another, mystery. Both are confrontations of the hidden or unknown, but one brings us to awe and the other despair. One can leave us feeling isolated and the other in wonder at our relationship to that which is so much greater than ourselves.

The space between the two is not in the level of knowledge but rather our relationship to the knowing and unknowing itself. In the midst of our unknowing, we are faced with a choice: passive uncertainty or the stumbling action of faith. The beginning of wisdom is not the expectation of certainty with knowledge but the understanding that the kind of life most worth living is always an act of faith.

Drying livestock carcasses and anguished faces of hungry women and children have become a common feature here as droughts increase due to climate change.

But now, in an effort to fight hunger, the Roman Catholic Church is making 3,000 acres of church-owned land available for commercial farming.

“We want to produce food, create employment, and improve quality of life for the people,” said the Rev. Celestino Bundi, Kenya’s national director of the Pontifical Mission Societies.

This is the first time the church has entered into large-scale farming, though it owns massive tracts of land across the country, most of which is idle and in the hands of dioceses, parishes, missionaries, and congregations.

“We have the will and the support of the community and government,” said Bundi.

“I think time has come for Kenya to feed herself.”

Photos depicting Gail Taylor's urban farming project at Three Part Harmony Farm

IT’S A MAY evening on the farm. My husband’s planting tomatoes and our son needs a bedtime story, but I’m completely occupied with pictures of war. I’ve cleared the piles of laundry from the kitchen table so our friend Adam can spread out his albums. There are photos of Adam in his tidy platform tent, of brown mountains in the distance, and dozens of pictures of children grinning on the other side of razor wire.

“This is an Aardvark,” he says, pointing to a gargantuan armored vehicle as he describes the flails that detonate buried mines. “What does that do to the soil?” I ask, because this is what you wonder when you and your family have been Mennonite farmers since the Reformation. There are a few more photos before I finally get it. Adam is showing me Bagram Air Base, the U.S. military hub in Afghanistan, surrounded by minefields and littered with burned-out tanks and planes, the wreckage of war from the Soviets. No one farms here, or has, or will for a long, long time.

FOR THE PAST three seasons, Adam McDermott has come to our farm in Central Pennsylvania’s Stone Valley every Friday morning to harvest vegetables for the food bank. We always chat while we bunch beets or pick green beans, and now I wonder why we’ve never talked about his years in the Army.

“This farm has definitely been part of my therapy,” he tells me, while offering a brief sketch of his months in Iraq: taking heavy equipment down unfamiliar roads to set off hidden explosives, being promoted to sergeant, and then losing three friends when a bomb shattered their Humvee. Adam came home in 2008 with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and an alcohol addiction. “A lot of guys struggle with alcohol,” Adam says. “In the military you have camaraderie and a sense of purpose. But when you get back, there’s just this big void.”