Donald Trump

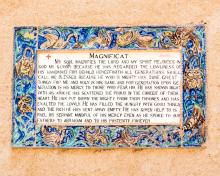

The scriptures assigned to the church during these days of hopeful waiting are filled with warnings against unjust rulers. This is repeated frequently in the Psalms, in the voice of one crying in the wilderness, and in the prayerful praise offered by Mary. The Magnificat, whose words are sung and prayed hundreds of thousands of times during these days, speak forcefully about the demise of the proud and conceited — and rulers who act like tyrants.

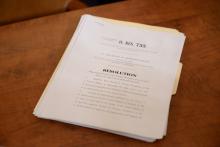

A Democratic-controlled House of Representatives committee approved charges of abuse of power and obstruction against Republican President Donald Trump on Friday, making it almost certain he will become the third American president in history to be impeached.

Democrats announced formal charges against President Donald Trump on Tuesday that accuse him of abusing power and obstructing Congress, making him only the third U.S. president in history to face impeachment.

And yet, despite these positive global examples, our situation in the United States is not unique. There are autocratic would-be strong men all over the world. They're rising, and none of them are known to practice servant leadership. They’re known as corrupt. They’re known as unprincipled. They’re known as perpetual liars. They’re known as people who are serving themselves, people who are serving their own wealth and power, but not serving those around them. And while we are in a time where this authoritarian style is on the rise, it’s as old as humanity itself.

This challenge to dismantle white supremacy and build a beloved community is one that white Christians need to undertake for the sake of their own obedience to God. Those of us who are white need to realize that this challenge and calling isn't for other people. It isn't for people of color who white people need to help.

During Obama’s second term, less than 50 percent of active federal judges were white men for the first time in American history, according to the Congressional Research Service. In under two years, President Donald Trump has reversed that trend. He has so far successfully appointed 152 individuals to judgeships in the federal circuit and district courts, of which 60 percent are white males. He has also filled two vacancies on the Supreme Court with conservative white males.

As a result of the political, religious, and moral crises we face today, both the soul of the nation and the integrity of faith are now at stake. This crisis is fundamentally about our chance and our choice of whether those who call themselves Christians are ready to go back to the teachings of Jesus, and whether such a call might be taken up by others beyond the churches. Many of us share a deep hunger for reclaiming Jesus instead of falling into more political polarization — we want theology to trump politics.

First of all, then, I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for everyone, for kings and all who are in high positions, so that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and dignity. This is right and is acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. —1 Timothy 2:1-4

This is a scripture passage that’s been on my heart quite a bit this summer, really since Donald Trump took office in January 2017. On the surface, it seems challenging to reconcile this instruction to offer thanksgiving to God for Trump, whose tenure in the highest elected position in the United States (and perhaps the world) has been filled with so much amorality and cruelty to so many groups of vulnerable people that, in Matthew 25, Jesus calls us to protect.

While we shouldn’t be sucked into Trump’s sinister game of getting distracted by and responding to every outrageous and egregious tweet or statement, there is also a corrosive and malignant danger of remaining silent. If we are silent, the cancer of racism will become more and more acceptable and normalized, emboldening white nationalists and supremacists and leaving already vulnerable communities even more vulnerable.

If we hear silence from white people of faith, we are in deep spiritual trouble. Christian moral objection to the president’s racist language must grow every day and from many quarters, but so farno word at all from the president’s most prominent evangelical supporters. Those Trump supporters have other issues and moral concerns, including differences with Democrats on abortion (as others of us do too); but will they call out the President on racism? That has now become an urgent moral and theological test.

AS WE MOVE into the hottest part of the summer and the likelihood that only two-thirds of the planet’s species will survive until the next election (oddly, presidential candidates as a species seem to be increasing), two things occur to me:

• I forgot to work on my beach body over the winter. And now it’s too late. (Next year, baby!)

• This might be a good time to check in on that climate change panel the Trump administration formed a few months ago.

The panel still has no official name, although any reference to it is usually preceded by “ad hoc,” which is Latin for “spitting distance.” It’s not clear if that distance is from reality, but we have a guess.

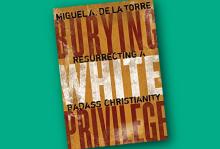

WHITE EURO-AMERICAN Christianity is dying, according to Miguel A. De La Torre, and from his point of view, its death is necessary. It has distorted the gospel with Euro-American nationalist ideals that benefit white communities at the expense of communities of color—heretical beliefs grounded in fear and exclusion, rather than love. In Burying White Privilege: Resurrecting a Badass Christianity, De La Torre deconstructs Donald Trump’s abundant evangelical support. In doing so, he offers guidance on how Christians can move forward.

Whiteness lies, he explains. It lies about the superiority of particular beliefs and nations. And this superiority complex has led to a lot of violence being done under the name of Christianity, including displacement, slavery, and genocide.

SINCE MY ARRIVAL in the U.S., I have looked forward to the day that I could enjoy the security of American citizenship. But as a green card holder of African origin, I now watch the Trump administration ramp up efforts to strip hundreds of naturalized Americans of their citizenship. With the establishment of a “denaturalization” task force, the supposed permanence of citizenship has become insecure.

In 2019, the Trump administration requested $207.6 million to review 700,000 immigrant files and develop elaborate efforts to punish people for past mistakes by denaturalizing them. As many keep their eyes on Trump’s pet project, the southern “border wall,” the administration continues to use taxpayers’ funds to construct harmful, longer-lasting obstacles to citizenship.

The “I” word, which Donald Trump calls it, is, of course, “impeachment” — the constitutional process of charging and, then in the Senate, convicting, a president for abusing the public trust and committing wrongdoing. The Constitution says that a president “shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” That is what is politically required — as the specifics for impeachment are ultimately politically decided. The other key word here is “crimes,” and who has the authority to conclude that they have been done by a president.

The Mueller report is all but forgotten — its limited focused also not remembered. Mueller’s assignment was to look only at Russian interference in the election and the possibility of a criminal conspiracy with the Trump campaign to assist this. Opponents of Trump labeled this “collusion.” Weeks before the report’s release, I argued that no such conspiracy would be found because none was needed. Putin detested Hillary and his apparatus of political infiltration was smart enough to know how to undermine her campaign. It did.

TO UNDERSTAND THE TRUMP PHENOMENON, which is at least in large part about race, I decided to read. Instead of reading more white people wrestling with what has gone wrong with white people, I, a white man, focused on African-American sources, mainly novels.

This move was first suggested to me by womanist ethicist Katie Cannon, who read the novelist Zora Neale Hurston as a primary source. I, too, began with Hurston, and then couldn’t stop. For two years, I have been reading classic novels by African-American authors, seeking an answer to these questions: How do black characters experience white people? How do they describe white Christian people’s morality and religion? The answers are clear—and devastating.

Discernment. That is what is most needed in a week of news like this one.

Donald Trump won the legal battle in this last week. Now he is trying to win the political battle. But the most important questions remain more than legal or even political: They are moral and ethical, and they are about the soul of America.

The New Zealand white power killer, a 28-year-old white Australian man, murdered 50 Muslims while they were worshipping and injured 50 more in two deadly Mosque shootings — the deadliest event of its kind in New Zealand’s history. He cited as inspiration Dylann Roof, a young white American man who murdered nine African-American Christians while they were studying the Bible at Mother Emanuel American Methodist Episcopal Church, in Charleston, S.C., after they had invited the stranger into their Bible study.

I REMEMBER THE EXACT DAY I discovered that some conservative Christians are not all that into democracy. It was 20 years ago. My daughter asked me for help with her social studies homework. I discovered that her Christian school taught a neo-Puritan civics curriculum, which proclaimed that God’s design for human government is rule by “godly Christian men” applying scripture under the sovereignty of God. I was shocked.

In the Trump era, we again witness a conservative Christian flirtation with authoritarianism. These conservative Christians compare Donald Trump to Cyrus of Persia—both authoritarian rulers, both “friendly” to but not part of God’s people, both supposedly used by God—and Trump is lauded as the president of divine providence in shlock films such as Liberty U.’s The Trump Prophecy.

Meanwhile, a quote attributed to Russian Orthodox priest and monarchist St. John of Kronstadt that “in hell there is democracy, in heaven there is a kingdom” is making the rounds on social media, occasioning much comment leaning in the direction of authoritarian rule. John of Kronstadt died in 1908 before the Russian revolution and likely associated democratic tendencies with atheism.

Of all the various surveys and polls I’ve seen leading up to today’s election, one was the most disheartening and depressing: The 2018 American Values Survey by the Public Religion Research Institute. While examining voters’ attitudes on a wide range of issues facing the electorate, most revealing are the views of white evangelicals. This constitutes nothing short of moral and ethical indictment, documenting with irrefutable evidence the failure of this group to embody many values of the gospel they confess.