Culture

Just in case you missed it (ICYMI), here's a roundup of new music that should be rocking your Spotify playlists.

Beth Orton: Sugaring Season

In her first release since 2006’s Comfort of Strangers, British singer-songwriter Beth Orton created a beautiful record leaning more toward the folk of her signature “folktronica” sound. Orton opts for stripped down, simplified arrangements, drawing mostly on acoustic guitars, strings, and her soft voice to propel each song. The music moves from the melancholy rich guitar sound of Nick Drake incorporating Simon and Garfunkel melodies to more upbeat, lighthearted tunes. The album, recorded in Portland, Ore., is a perfect companion for a drive through countryside of the Pacific Northwest.

Highlights: “Magpie,” “Call me the Breeze,” “Mystery”

Lord Huron: Lonesome Dreams

The brainchild of singer-songwriter Ben Schneider, the music on Lord Huron’s first LP Lonesome Dreams is surprisingly reflective of its album art. (A designer friend of mine once advised me to take any direction I wanted when designing an album cover because they “usually don’t have to make any sense.”) On the grainy cover is a painting of a lone horse rider under the night sky of the desert. Much like the openness of the desert, the songs are expansive and feel like they have depth. The ethereal expanses laden with reverb, sitar, and moon chimes lend themselves well to the picture of the desert sky. Lonesome Dreams feels both antique and refreshingly new. Its themes are large — love, loneliness, and that itch to explore— but it doesn’t at all feel preachy or overzealous.

Highlights: “Ends of the Earth,” “Time to Run,” “She Lit a Fire”

God Girl's New Favorite Thing for Oct. 12, 2012:

Ethiopian Pop StarTeddy Afro

ADDIS ABABA — Pretty much everywhere we've gone in Ethiopia this week, we've heard Teddy Afro's voice.

The 36-year-old Ethiopian singer whose given name is Tewodros Kassahun or ቴዎድሮስ ካሳሁን in Amharic, the national language of Ethiopia, is sometimes referred to as the "Michael Jackson of Ethiopia." But, to my ear at least, he's more the equivalent of, say, Ethiopia's Usher (if he were more political, that is.)

Afro's debut album, 2001's Abugida, spawned several hit singles, including "Halie Selassie" (his tribute to the late Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie I), and "Haile, Haile," which honored Ethiopian Olympic runner Haile Gebrselassie.

An extended interview on biblical womanhood with Rachel Held Evans.

Why, exactly, does it matter if President Barack Obama gave a lackluster performance in the recent presidential debate?

These quadrennial campaign sideshows have nothing to do with one's capability, preparation, aptitude or suitability for the presidency.

Why does Gov. Mitt Romney's spirited performance matter? What does a “victory” by one candidate mean, other than momentary bragging rights?

Surely we know that these debates are about as meaningful as an Oscar winner's thank-you speech. What we want from a president is a steady hand in dealing with a wicked and wayward world, a collaborative spirit in bringing a broad reach to government, and a magnanimous spirit in consoling war widows, helping victims of disaster, protecting the weak from the relentless predations of the strong, and trying to preserve an “American Dream” to which all, not just a few, are invited. We want signs of character, not a telegenic mien.

Presidential debates are like first visits to possible in-laws. You hope not to belch at supper — and then you return to the world where you are actually exploring marriage and building a life.

Among my must reads are the Sunday New York Times Book Review and other book reviews I come across in various media outlets. There are too many books being published that I would love to read, but just don’t have the time. So, I rely on reading book reviews as one way of keeping in touch with what’s being written.

Here are my picks of this week’s books.

Battlestar Galactica—not the first thing you think of while mining the vast array of influences on an indie rock record. Even more surprising might be Carl Sagan’s The Cosmos or the History Channel’s Ancient Alien Theory. But all three shows played vital parts in inspiring Freelance Whales’ newest record Diluvia.

“All three of those shows have an abundance of emotional storytelling that we just found really inspiring,” said Chuck Criss, who plays banjo, bass, synthesizer, glockenspiel, harmonium, acoustic and electric guitar, and provides vocals for the band. “[But] I don't want to give the impression that we made a Bowie sci-fi record.”

While they may not have set out to make another soundtrack to 2001: A Space Odyssey, the sci-fi influences are definitely apparent on Diluvia, particularly in the twitchy electronic sounds that open and close most of the album’s songs as well as the ambient, spacey atmosphere permeating Diluvia. Both are a far cry from the quintet from the Queens’ opening album, Weathervanes (2009), which they described as “layered, textured pop music.”

OK, the @firedbigbird tweets have been hilarious.

And it's almost understandable that America has given so much attention to the Big Bird comments from Tuesday's debate. (@Firedbigbird had more than 31,000 Twitter followers as of late Friday afternoon.)

I mean, Romney's comment was definitely a "zinger."

We get it. It's funny. But come on.

On Thursday, Public Broadcasting System (PBS) CEO Paula Kerger talked to CNN about the issue, and she couldn't believe the iconic children's TV star has gotten this much attention either.

THE SKIES LOOK different to me these days. The soft and tranquil clouds of my youth that often reminded me of cute Disney characters—a misty Dumbo drifting languidly overhead—have mostly been replaced by dark and threatening formations, more reminiscent of Disney’s lesser-known films, such as Godzilla vs. The Little Mermaid: This Time It’s Personal. More specific, the violently roiling skies of late are like a scene from Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds, where intense storm clouds heralded an alien invasion.

Which is why I always carry a prepared speech of surrender in my backpack, in case I need to immediately declare loyalty to a superior race. Although, so far, the alien presence has been pretty unimpressive, consisting mainly of crude, humanoid Kardashians attempting to assimilate quietly. One hopes that when the next prototypes arrive, they will better conceal the vaguely reptilian features of their planet’s indigenous life forms. Not to mention vice presidential hopeful “Paul Ryan,” whose hairline displays the telltale widow’s peak once thought to be a unique facial characteristic of earthly vampires, until NASA rovers spotted it on a rock on Mars. (Mars reportedly privatized its health care for seniors decades ago, and just look at the place now: not an elderly person in sight.)

BUT WHAT WAS I talking about? Oh yes, the weather. The typical forecast this summer included phrases such as “hurricane-force winds,” “damaging hail,” and “start hoarding toilet paper.” Of the four mature trees in our yard, only one remains, having survived repeated gale-force winds through pluck and attitude, although having a trunk the circumference of a grain silo probably helped. (I could never get my arms around it for a hug, back when I used to do that sort of thing.)

THE DOCUMENTARY film The Economics of Happiness, produced by the International Society for Ecology and Culture, begins starkly, with full-screen titles that tell us we are facing an environmental crisis, an economic crisis, and a crisis of the human spirit. As the film goes along, it strongly suggests that those three crises are interrelated.

In the end, the filmmakers and their multicultural array of talking heads ask that we stop measuring human progress simply by economic growth and give priority to the quality of life, the health of communities and their cultures, and the sustainability of our economic practices. In short, they suggest replacing our mad rush toward globalization with a back-to-the-future move to “localization.”

Early in the film, writer-director-narrator Helena Norberg-Hodge tells us about the people of the remote Ladakh region of the Himalayas, one of the highest spots on earth to be inhabited by a settled human community. When Norberg-Hodge first visited the Ladakhis in the 1970s, she says, they were self-sufficient, healthy, and mostly at peace, with themselves and each other. Then came the great Western world with its bells and whistles and manufactured needs. Soon the people became dissatisfied with their traditional way of life and were driven to compete in a cash economy. Before long, there was open hostility between Muslims and Buddhists, who had co-existed peacefully for centuries, a fraying of the social fabric, and an atmosphere of gloom and depression.

He uproots teeth primordial in nature and that eat his soul

with appetite the size of mercenary forces plundering a city

whose inhabitants do not fight back because most of them

are women, children, and animals that creep on all fours.

He knows of a city not spared and is without name, unlike Nineveh,

whose repentant king decreed:

Human beings and animals shall be covered with sackcloth,

and they shall cry mightily to God.

Complete with pictures, The Gospel of Rutba: War, Peace, and the Good Samaritan Story in Iraq (Orbis, 2012), by Greg Barrett, details a remarkable story of generosity, hospitality, and community between the citizens of two warring nations. After three U.S. Christian peace activists visiting Iraq were nearly killed in a car accident outside the bombed-out town of Rutba, Iraqi Muslims came to their aid and initiated a sacred friendship. This “good news” amidst war is a gospel worth retelling.

With both truth and grace, Logan Mehl-Laituri—an Iraq combat veteran turned conscientious objector—explains in Reborn on the Fourth of July: The Challenge of Faith, Patriotism, and Conscience (InterVarsity Press, 2012) how the glorification of military service does not live up to the reality of war. A compelling read for churches and Christians struggling with questions of faith, patriotism, and violence.

Coauthored with human-rights journalist Julia Lieblich, Wounded I Am More Awake: Finding Meaning After Terror (Vanderbilt University Press, 2012) recounts the extraordinary life of Esad Boskailo—a doctor who survived the genocide in Bosnia and now helps victims of terror as a psychiatrist specializing in trauma recovery. Employing a human-rights framework rather than a theological one, this book illustrates how storytelling can be healing—a timely lesson for congregants, churches, and clergy as they grapple with the problem of evil in an age of terror.

TECHNICALLY, the Tucson Unified School District did not ban any books after the Dec. 27, 2011, state court ruling that upheld the Arizona Education Department’s order finding the Mexican American Studies program illegal. But in January, the school district removed from classrooms seven books it said were referenced in the ruling and put them into remote storage. The district, according to Roque Planas of Fox News Latino, also “implemented a series of restrictions ranging from outright prohibition of some books from classrooms, to new approval requirements for supplemental texts, and vague instructions regarding how texts may be taught.”

Former Mexican American Studies teachers have been instructed to not use their former curricula or instruct students to apply perspectives dealing with race, ethnicity, or Mexican American history. So, for example, Shakespeare’s The Tempest can still be taught—but former Mexican American Studies instructors have been advised to avoid discussion of oppression or race (which have long been taught as themes of the play, even in predominantly white classrooms many miles removed from Tucson).

Author’s Note: When Arizona House Bill 2281 was used to dismantle the Mexican American Studies program in Tucson public high schools earlier this year, books used in the courses were removed from classrooms—in at least one school as students watched. Most of the titles, but not all, were by Latino writers.

Instead of swallowing their dismay, several students documented what they witnessed through social media. That’s how members of the Houston-based writers’ collective Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Having Their Say heard about what happened in Tucson. Incensed by the stifling of knowledge, they organized the Librotraficante (literally, “book traffickers”) book caravan. Their goal was to “smuggle” the “contraband” books back into Tucson, and bring attention to what critics contend is a troubling combination of anti-intellectualism and the state’s anti-immigration stance enacted earlier.

Nuestra Palabra members worked with partner organizations along the caravan route to hold press conferences and celebrate Latino arts and culture at several Librotraficante book bashes. In addition to the public events, the five-day journey stopped in six cities, seeding Librotraficante underground libraries along the way. This is a reflection on riding the Librotraficante caravan, which took place in mid-March.

SEEDS. My parents were farm laborers for part of their young adult lives. They did that body-leeching work in the hot Texas sun, picking and hauling cantaloupe, watermelon, onions, and anything else that required a human hand.

My life has been very different from theirs. I make a living working at a desk. But I keep an image near my computer: It’s a black-and-white photo of farm laborers working a field. Bent at the waist, their arms hang from their torsos, grazing the ground like roots recently pulled from the earth. Whenever I start whining—about how hard my chair is, or that my computer is too slow, or that my agent doesn’t love me as much as his other clients—I look at this photo. I work, but the kind of work shown in the photo is grinding and thankless.

Because the workers’ faces are hidden in the shadow of broad-brimmed hats, I feel that I know even less about them. I don’t know their story. What I do know is that the spinach, tomatoes, and onions I enjoy on a chilled plate are because of these faceless, distant people. And yet, I know I’m not that far removed from them. Besides our shared heritage, it’s hard not to feel a sort of kinship to someone who makes it possible for food to appear on your plate.

Since the establishment of The Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood in 1987 and J.I. Packer’s 1991 article “Let’s Stop Making Women Presbyters” in Christianity Today, there’s been a resurgence of traditionalist theology among some American churches. Instead of advocating “male headship,” they now promote “complementarianism.” Instead of portraying women as intrinsically “serving, subordinate, and supportive,” they now advocate “biblical womanhood.” But it’s the same patriarchal heresy, just with new language.

Rachel Held Evans, a Tennessee-based evangelical Christian raised in conservative Christian churches, decided to turn the tables. She vowed to take all of the Bible’s instructions for women as literally as possible for a year. A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband Master is the often-hilarious, engaging, well-researched, deadly serious result. (You can read all about her adventures at rachelheldevans.com). Former Sojourners editorial assistant Betsy Shirley, a student at Yale Divinity School, interviewed Evans in August 2012.

Should the market have so much control over liturgical music?

There is nothing new to this question. Not at all. Now, however, there may be much that is new in discoverng the answer.

Once upon a time in the European West, liturgical music was created by musicians who were supported by the patronage of a noble class.* Byrd, Tallis, you know the gang.

Before then it was the monastic composer (Hildegard, et al) who seemed to rule the charts with their chant. Musicians were supported by the Church and the Wealthy in some way and thus created music for worship.

The old markets, of course, have given way to new markets over the centuries, but throughout the history of the Western marketplace, markets (and the people they represent) have had tremendous say in what music we deem as sacred.

Now, in our post-colonial, neoliberal marketplace, how shall we choose liturgical music?

Respected news outlets unwittingly sent a lie around the world on Sept.12: a Jew backed by 100 Jewish donors made a film insulting Islam's Prophet Muhammad.

Within a day, the lie unraveled. But the damage to the Jewish community had been done, and Jews will continue to suffer for it, say Jewish civil rights leaders.

“This is another blood libel that’s in place,” said Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, referring to a history of conspiracy theories that has fueled anti-Semitism for centuries.

Apparently even Tim Cook doesn't use the new maps app on iPhone 5. Shocker.

Also, some Grandmas meet Star Wars, Algae gets fed by an opera singer, someone took some sweet Iceland photos, and some Portland people have created a cologne that can make hipsters with beards smell like campfires! These links are awesome.

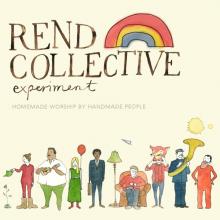

God Girl's New Favorite Thing for Sept. 27, 2012: Northern Ireland's Rend Collective Experiment

I love music. I love Jesus. And I love all things Irish.

So when a friend introduced me to Rend Collective Experiment last year, chances were pretty good that I'd vibe with this band from the North of Ireland (Bangor, to be specific.)

But ... and this was a BIG but ... my musical proclivities, while decidedly ecclectic, generally steer clear of contemporary Christian worship music (especially if it's billed as such.) When it comes to having a musical worship experience, give me Chris Martin and his bandmates, or those other four greying boyos from a little farther south in the Republic of Ireland.

Without putting too fine a point on it, Rend Collective are very much a contemporary Christian worship band. But they aren't what you're thinking.

Neither painfully earnest nor woefully twee. They're fun and funky — earthy, too, in a grab-your-banjo-and-trilby-hat kind of a way.

"High nigh br-eye-n, K-eye"? Come again? Rend Collective and Bart Millard (of the band MercyMe) give us a lesson in how to speak Northern Irish.

“Are Mumford & Sons as big in America as they are here?” my English friend asked me a year ago over a pint at a pub on High Street in Oxford, England.

“Uh … yea,” I replied, astonished that their popularity was even in question. “They’re huge.”

Turns out that English friend is Marcus Mumford’s cousin, and he eventually got to see how big they are in the states, spending this past summer in Arizona and scurrying over to Colorado for their show at Red Rocks. (I know I’m jealous.)

But has that popularity and success translated into a decent sophomore album? Absolutely. One way to avoid the perilous “sophomore slump” that plagues many musicians and bands these days is to stick to your guns. And that’s exactly what English quartet Mumford & Sons did with their second album Babel.

“The idea was always, ‘If it ain’t broke, why fix it?’” producer Markus Dravs told Rolling Stone.

And that’s almost exactly what audiences get on Babel. It’s as if Mumford took all the good things from their first record, Sigh No More, and channeled them into Babel.

Who blames ‘em? Their foot-stomping, banjo-plucking signature folk-rock sound has sent them to the far corners of the earth and back. It also shot Sigh No More up to platinum status, selling five million copies and nominating the band for two Grammys.