Culture

I love Fun.. I especially love the wacky period at the end of the band’s name. But my Word doc has the green squiggly line under the two periods of that first sentence. I hate that green squiggly line — it’s not fun. It’s there to tell me that I have bad grammar. Not this time, Word doc! I shall right click and ignore you!

Fun.’s (okay, now there’s a red line! Once again I shall ignore…) Some Nights is full of philosophical and spiritual gold. It asks questions about identity, friendship, violence, and the purpose of life. But, for me, these words stand out the most:

My heart is breaking for my sister and the con that she calls “love”

When I look into my nephew’s eyes…

Man, you wouldn’t believe the most amazing things that can come from…

Some terrible nights…ah…

I really did not like Michael Pollan's newest offering, Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation. Here are three reasons why:

1. The premise feels phony and staged.

Pollan has said that he is “more at home in the garden than the kitchen” (In Defense of Food), but this modesty about his cooking skills is less than convincing to those who read The Omnivore’s Dilemma, in which he prepared a highly local meal of wild pork cooked two ways, bread leavened with wild yeasts he captured himself, and a sour cherry galette with fruit from Pollan’s own trees.

He’s born poor. By age 6, he’s an orphan. Two years later, he loses his grandfather. Yet he overcomes his circumstances, develops a reputation for business integrity and progressive views on marriage.

Then he becomes a prophet of God.

The portrait of the Muslim prophet, which emerges from a PBS documentary “Life of Muhammad,” may surprise some American viewers.

Eugene Allen served eight presidents as a White House butler, and his legendary career is the inspiration for Lee Daniels’ The Butler, a film starring Oprah Winfrey, Jane Fonda, and a host of A-list Hollywood talent.

But members of The Greater First Baptist Church knew the man who died in 2010 by other titles: usher, trustee, and a humble man of quiet faith.

Fred Bahnson’s first bit of advice when he started planning a church garden eight years ago came from an elderly tobacco farmer who grabbed a handful of soil, rolled it around in his fingers and shook his head:

“You don wohn fahm heah,” he said in his deep North Carolina drawl.

Those were not the only discouraging words he received as he planted and cultivated one of the earliest and most successful church gardens, 20 miles north of Chapel Hill.

But Bahnson, a Duke Divinity School graduate and a pioneer in the church gardening movement, had a different view of farming than the older tobacco farmer. He knew that if he gave back to the soil more than he took out — in the form of compost, manure and other soil food — he could create an abundant garden.

Amy Ray’s smile opened itself to wrap love around the couple thousand fans who’d weathered a soggy soaker of a spiritual festival to wait for their 10 p.m. Saturday set. “Y’all have advanced way past kum-bah-yah,” she quipped. “That was a deep album cut.”

For 90 minutes, Ray and her musical partner Emily Saliers couldn’t stop praising the Wild Goose Festival crowd. It’s as if they’d trekked to the misty mountains of western North Carolina just to see us render their greatest hits the new hymnal for progressive and inclusive Christianity. The stellar setlist covered all the ground, a collection of tracks both new and old spanning a career that jump-started itself in the same 1980s Georgia music scene that gave us the likes R.E.M. and Widespread Panic.

The Indigo Girls catalog knits itself into our daily lives in such a way to make them the perfect band for a campfire singalong at a radicals’ revival like this. But what else was obvious here could not be pinpointed in the mere practice of song. The best-selling grassroots folk duo found something in our makeshift festival that’s been true of their career — past all the great lyrics and legacy of activism, past the DIY-ethics and indie entrepreneurs' edge, past all the albums and compilations, past all the accolades — exists the chewy center of hope. We see the Holy Spirit at work in such a down-to-earth humbling and fiery fashion. The Indigo Girls headline set at Wild Goose 2013 healed the audience and sealed the festival’s cultural location in a jubilant justice movement for ecumenical and evangelical convergence on the funky fringes of mainstream Christianity.

Don’t sing love songs, you’ll wake my mother

She’s sleeping here right by my side

And in her right hand a silver dagger,

She says that I can’t be your bride.

— from “Silver Dagger” by Joan Baez

It was their song — the young, winsome brunette and her silver-pated lover with the sparkly eyes.

“All the love and all the death in me are at the moment wound up in Joan Baez’s ‘Silver Dagger,’” the man wrote to his lady love in 1966. “I can’t get it out of my head, day or night. I am obsessed with it. My whole being is saturated with it. The song is myself — and yourself for me, in a way.”

He yearned for her. He was heartbroken. And he was Thomas Merton — the Trappist monk, celebrated author, and perhaps most influential American Catholic of the 20th century.

It’s a chapter of the thoroughly modern mystic’s life that is no secret to his legions of fans, detractors, and scholars of his prolific work, including the best-selling autobiography, The Seven-Storey Mountain.

Now Merton’s complex love life is the subject of a forthcoming feature film, The Divine Comedy of Thomas Merton.

Troy Bronsink’s meditative live album Songs to Pray By stretches its sonic arms to embrace every listener with expansive words of spirited awe and awesome humility, with ecstatic waves of audio grace and rhythmic gravity.

Bronsink and his band bring to church what we’ve seen out on the festival circuit for years: a shimmery and psychedelic use of sound and language to elevate listeners who choose to inhabit a song as if it were wings, the place where the spirit soars and the heart sings. We don’t often associate noodly guitars and trippy percussion with the worship sound, which is exactly why this album is such a perfect addition to the praise genre.

A solo Bronsink will be presenting his musical work tomorrow at the Wild Goose Festival. We both took a break from packing and planning our journeys to North Carolina for this email interview.

Eva Piper considered herself a shallow Christian until the accident that revitalized her faith and turned her Baptist pastor husband, Don Piper, into the best-selling author of “90 Minutes in Heaven.”

“It wasn’t until Don’s accident that I really opened myself up to a really honest relationship with the Lord,” said Eva Piper, who says she’s embarrassed to recall her superficial faith.

Eva Piper writes about life after her husband’s alleged visit to heaven in “A Walk Through the Dark,” released on July 30. Her book comes nine years after the publication of her husband’s book, which spent more than five years on The New York Times’ best-seller list.

I’m excited to share this mixtape in honor of the Wild Goose Festival, Aug. 8-11 in Hot Springs, N.C.

For the festival proper, this third one will surely be a charm. But for me, it’s the second time around, hence the title of this playlist, also taken from an Indigo Girls song. Getting ready for a music festival for me requires hours upon hours of research: buying and downloading mp3s, studying sounds with the headphones on. These are just a few favorites I’ve found and suggestions for your weekend—mixing up the indie-folk with the psychedelic-liturgical with the pop-folk and power-pop.

The mixtape works like a storybook of sonic massage on the ears, guts, and heart. My prayer is that your listen will provide at least a sliver of the joy that making it offered. Hopefully you can allow this mix to accompany your packing routine or en route roadtrip. See you at the shows! Or if you cannot make it, hopefully these songs will remind you why you wish you could.

SINCE WE NOW know the federal government has been monitoring our every move for years—recording our telephone calls, reading our emails, trying to friend us on Facebook (“you have 295,984,457 mutual friends!”)—I wanted to clarify a few personal remarks that may have been misconstrued by NSA computers; computers which, I might add, are doing a heckuva job.

When I emailed a friend that I thought I “killed” at a recent gathering, I meant that I was particularly amusing that evening. I was not bragging about some heinous crime, which I would never commit anyway because, frankly, that’s not where the laughs are.

But “killed” looks bad in cyberspace, even though it’s something comedians want to do, as opposed to “bombed,” which is the opposite of “killed,” although NSA computers probably recognize a certain similarity between the two and automatically alert law enforcement officials. But again, the word “bombed” is a comedy concept meaning, variously, “wishing you were dead as an audience sits silently in judgment,” or for me, who entertains mainly in the homes of friends, “wishing you were dead, because people are laughing about you in the kitchen.”

But living in a free society means we shouldn’t have to watch what we say to avoid the unwanted curiosity of federal authorities. Heck, I get into enough trouble just trying to cheer up taciturn gatherings. (“Hey, is this a party or a funeral, hah hah?! What? Oh, sorry, I didn’t notice the flowers. Yes, he’ll be missed.”) On second thought, maybe a few days of secret CIA interrogation might do me some good. (“Were you under instructions from al Qaeda when you embarrassed your host by juggling the dinner rolls? Are there other social events you plan to terrorize or disrupt in the near future?”)

IN HIS EULOGY at Baptist pastor, civil rights activist, and author Will D. Campbell’s memorial service in late June, Campbell’s close friend, journalist John Egerton, recalled their first meeting. Campbell was wearing the broad-brimmed black hat that became his signature, with jeans and cowboy boots. At the time, Egerton noted, Campbell was in the middle of “a costume change” from the tweed jacket, clerical collar, and calabash pipe he had affected as a young, Yale-educated liberal minister.

Campbell was a notoriously theatrical figure, as famous for his hats and walking sticks as for his theological pronouncements. In fact, in the 1980s Campbell became a cartoon character in the guise of Rev. Will B. Dunn in the late Doug Marlette’s “Kudzu.” Campbell also dramatized his own life in Brother to a Dragonfly, his National Book Award-nominated 1977 memoir, and in a 1986 sequel, Forty Acres and a Goat.

Another favorite prop in the Will Campbell show was the acoustic guitar he would strum while singing his own country compositions and old favorites like “Rednecks, White Socks, and Blue Ribbon Beer.” Campbell, who was based in Nashville from 1957 on, also became a sort of chaplain to the “outlaw” element in that city’s country music industry. He traveled on Waylon Jennings’ tour bus, and Jennings’ widow, country star Jessi Colter, sang at Campbell’s memorial.

THE MAXIM states that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. But what happens when well-meaning Christians construct and lead others down that road? In her new book The Child Catchers: Rescue, Trafficking, and the New Gospel of Adoption (PublicAffairs), investigative journalist Kathryn Joyce explores how some evangelicals have fueled the global adoption frenzy—and how adoption reform advocates are trying to stem the tide of trafficked children (and the rampant spread of misinformation) across borders. Sojourners contributing writer Brittany Shoot recently spoke with Joyce.

Brittany Shoot: Why do you think it’s been primarily evangelicals who have led the surge in international adoption?

Kathryn Joyce: The idea of the “global orphan crisis” needs some unpacking. People who talk about this crisis often cite UNICEF estimates that there are between 150 and 210 million orphaned children in the world. While the figures actually refer to a wide range of orphaned and vulnerable children in need of services, often people only hear the word “orphan” and presume these children are parentless kids in need of new homes. In fact, most of these children have a surviving biological parent or other extended family who may need some support.

Additionally, adoption has become a powerful metaphor in many evangelical churches studying and preaching what has become known as adoption or orphan theology. Many leaders within the movement teach that earthly adoption is a perfect mirror of Christian adoption by God, and it’s a way that Christians can put their faith into action in a very personal manner. Evangelicals have been encouraged to adopt by this theology as well as by other developments in their churches or denominations, such as the Southern Baptist Convention’s 2009 resolution that asked its members to prayerfully consider whether God was calling them to adopt.

CYNTHIA MOE-LOBEDA is a Lutheran feminist ethicist trained at Union Theological Seminary in New York who teaches Christian ethics, gender, and diversity studies at Seattle University. The author of several previous books in Christian social ethics, she has emerged as a significant voice in contemporary Christian economic, ecological, and public ethics.

The evil considered in Resisting Structural Evil is primarily the collective ecological and economic damage being done by wealthy global North folk—such as most readers of this review—through the indulgent and wasteful way of life that we have been socialized into accepting as normal despite its disastrous implications and effects. This evil is structural and driven largely by the unaccountable and nearly unlimited power of the modern corporation.

One reason our ecological and economic injustice can be labeled as evil is because it is largely hidden from our eyes—or if we see it, it is accepted as simply the way things are and always have been and always will be. So we live off the suffering of the people whose land we take or despoil, or whose livelihoods we destroy, or whose water we poison, or whose labor we exploit to get our “everyday low prices.” And we go merrily about our wealthy and comfortable way in a state of what the author describes as “moral oblivion.”

Moe-Lobeda takes the reader on a journey intended to end such moral oblivion. I find the book to be primarily an exposé of the connections between the “American way of life” and the injustices on which it is built—and which it perpetuates. Among these injustices is harm to the earth, which has both terrifying long-term implications for the livability of our planet in the future and concrete short-term costs for those invisible neighbors of ours who suffer ecological harm so that we might drink our soft drinks and get the latest electronics.

DURING MY EARLY years of sobriety, I spent most Monday nights in a smoke-filled parish hall with some friends who were also sober alcoholics, drinking bad coffee. Pictures of the Virgin Mary looked down on us, as prayer and despair and cigarette smoke and hope rose to the ceiling. We were a cranky bunch whose lives were in various states of repair. There was Candace, a suburban housewife who was high on heroin for her debutante ball; Stan the depressive poet, self-deprecating and soulful; and Bob the retired lawyer who had been sober since before Jesus was born, but for some reason still looked a little bit homeless.

We talked about God and anger, resentment and forgiveness—all punctuated with profanity. We weren’t a ship of fools so much as a rowboat of idiots. A little rowing team, paddling furiously, sometimes for each other, sometimes for ourselves; and when one of us jumped ship, we’d all have to paddle harder.

In 1992, when I started hanging out with the “rowing team,” as I began to call them, I was working at a downtown club as a standup comic. I was broken and trying to become fixed and only a few months sober. I couldn’t afford therapy, so being paid to be caustic and cynical on stage seemed the next best thing. Plus, I’m funny when I’m miserable.

This isn’t exactly uncommon. If you were to gather all the world’s comics and then remove all the alcoholics, cocaine addicts, and manic depressives you’d have left ... well ... Carrot Top, basically. There’s something about courting the darkness that makes some people see the truth in raw, twisted ways, as though they were shining a black light on life to illuminate the absurdity of it all. Comics tell a truth you can see only from the underside of the psyche.

CINEMA IS poetry, not prose, and so looking for “realism” in movies is an ambiguous task. Perhaps the better comparison would be with memory, for the way we experience the past might feel a little bit like a film unspooling in a low-lit room, the images urging themselves onto a wall with frayed paper, red-hued, with the sound fading as I get older. Like the opening of the film of Carl Sagan’s novel Contact in reverse, in which all the radio signals that have ever been broadcast speak their way into deep space, the further away I get from a memory, the more like an old movie it seems.

The role that cinema plays in memorializing the past is unparalleled—for both the way we experience memory and the memories themselves are uniquely bound up in each other—Casablanca or There’s Something About Mary alike may remind us of past loves, and perhaps also of the time and place we saw those movies, and watching either of them again enables us to re-experience the very emotions we may have first experienced by watching it. When we experience movies like memories, we meditate rather than consume, and do what Pascal suggested was the antidote to all the problems in the world: sitting still for 10 minutes and thinking. At the cinema we take a walk in our minds and, through an art form that is usually less controllable than reading or listening, we are taken somewhere new.

The Dream at 50

This August marks the 50th anniversary of the historic March on Washington for civil rights for African Americans. PBS will feature special broadcast and Web programming, including the premiere of the new documentary The March onTuesday, Aug. 27 (check local listings). pbs.org/black-culture/explore

The Miracle of Meaning

Secular Days, Sacred Moments: The America Columns of Robert Coles, edited by David D. Cooper, collects 31 short essays by the respected child psychiatrist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author. Whatever the topic, Coles offers thoughtful insights on civic life and moral purpose. Michigan State University Press

IN 1900, long-simmering resentment over increasing foreign presence and exploitation in China boiled over into a full-scale uprising, the Boxer Rebellion. It was spearheaded by the “Righteous and Harmonious Fists,” a peasant secret society whose members practiced martial arts—Westerners, observing their exercises, dubbed them “Boxers.” The Boxers targeted foreign officials, merchants, and missionaries, as well as Chinese Christian converts.

Comic book author and artist Gene Luen Yang illuminates two very different fictional perspectives on this conflict in his new two-volume graphic novel Boxers & Saints: The first volume, Boxers, tells the story of Bao, a boy who becomes a Boxer leader after seeing ongoing abuse by Westerners; Saintsfollows Four-Girl, an unwanted daughter who converts to Catholicism, takes the name Vibiana, and must flee the Boxers.

Yang’s 2006 work American Born Chinese was the first graphic novel to both win the Michael L. Printz Award for excellence in young adult literature and to be nominated for a National Book Award. He lives in Oakland, Calif., and teaches in the Hamline University MFA program in writing for children and young adults. Sojourners senior associate editor Julie Polter interviewed Yang in July. Boxers & Saints releases in September from First Second Books.

Julie Polter: The characters in Boxers & Saints are driven by varied combinations of ideology (patriotism, cultural imperialism) and mysticism/faith. The flaws and virtues of different beliefs seem to mirror each other. What led you to this complicated story?

Gene Luen Yang: The genesis of the project was out of my own conflicts. I majored in computer science in college and minored in creative writing. I had a professor who was also a novelist, Thaisa Frank. I remember visiting her during office hours and talking to her about my struggles with writing about issues of faith. Faith, especially in college, became very important to me; it became a critical part of how I saw my place in the world. It was really hard for me to put something authentic on the page. Her advice to me was, essentially, you have to write your life and live your faith—you don’t ever try to write your faith, because it will come out funky. That’s the advice I’ve tried to follow ever since.

they will kill you

and say I’m sorry

and expect your mother to

forgive and forget

she ever gave birth to you

carried you in love for nine months

endured labor

and pushed you out with God’s might moving in her hips

ever fed you life from her bosom

or how you smelled like heaven after she washed you

that she ever watched you take your first steps

speak your first words

ever tucking you into bed with stories that rocked you to sleep

the many nights she prayed for your protection

or how excited she was the day you gave your first recital

that she ever taught you to be good and kind

ever beamed with pride

whenever you got an A on your test

that she ever wanted the best in this world for you

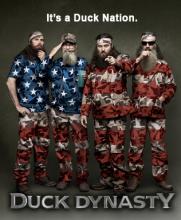

Hollywood producers often break every rule when it comes to publicizing faith and politics. But A&E’s smash hit reality show, Duck Dynasty, puts it front and center.