Don’t sing love songs, you’ll wake my mother

She’s sleeping here right by my side

And in her right hand a silver dagger,

She says that I can’t be your bride.

— from “Silver Dagger” by Joan Baez

It was their song — the young, winsome brunette and her silver-pated lover with the sparkly eyes.

“All the love and all the death in me are at the moment wound up in Joan Baez’s ‘Silver Dagger,’” the man wrote to his lady love in 1966. “I can’t get it out of my head, day or night. I am obsessed with it. My whole being is saturated with it. The song is myself — and yourself for me, in a way.”

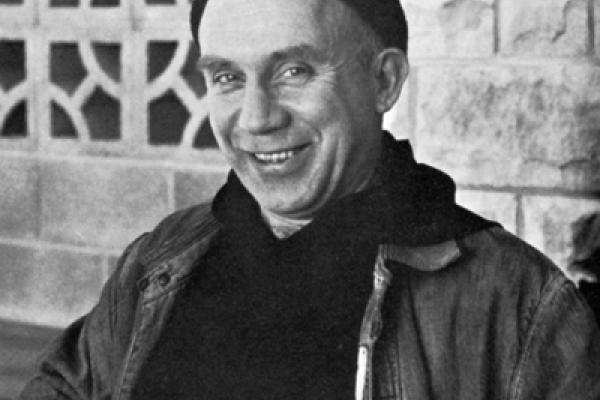

He yearned for her. He was heartbroken. And he was Thomas Merton — the Trappist monk, celebrated author, and perhaps most influential American Catholic of the 20th century.

It’s a chapter of the thoroughly modern mystic’s life that is no secret to his legions of fans, detractors, and scholars of his prolific work, including the best-selling autobiography, The Seven-Storey Mountain.

Now Merton’s complex love life is the subject of a forthcoming feature film, The Divine Comedy of Thomas Merton.

Read the Full Article