Clergy

“We’re really not talking about anything changing,” said Mary Ellen Kruger, chair of the five-member board of directors of SNAP. “Our everyday mission is the same: helping survivors, protecting kids through education, and exposing predators. So that’s not changed.”

Image via NYCStock/Shutterstock.com

Dec. 4 was a beautiful reminder, in the long struggle for justice, that, no matter how long we wait, God hears our cry. And love and justice will win.

A few weeks ago, Chief Arvol Looking Horse issued an invitation to clergy and faith leaders to stand in solidarity with the people of Standing Rock. He said he was hoping maybe 100 would respond. But I joined thousands, in a procession of faith leaders, to gather around the sacred fire at the Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock.

I knew something special was happening here.

Roman Catholic bishops in Rwanda have issued an apology for the role played by individual clergy and church members, in the 1994 genocide in which nearly 1 million ethnic Tutsis and Hutus were killed.

On Nov. 20, the apology was read aloud in all Catholic churches, in the local Kinyarwanda dialect. It came at the end of Pope Francis’ Jubilee Year of Mercy.

Pope Francis on [Nov. 11] made a surprise visit to meet several men who took the controversial step of leaving the priesthood and starting a family.

A Vatican statement said the pope left his residence in the afternoon and traveled to an apartment on the outskirts of Rome, where he met seven men who had left the priesthood in recent years. The pontiff also met their families.

Clergy have long been expected to be paragons of piety and purity. As public religious figures, we’re assumed to represent the moral ideal — an example for others to follow — and as a result, we become archetypes rather than human beings. We are measured up against an image of what a perfect Christian pastor should look like.

Image via Goias Courts of Justice / RNS

A pioneering mediation program in Brazil is banking on religious leaders using their conciliatory skills to resolve conflicts between families and neighbors, while helping the judicial system reduce a massive backlog of cases overloading the country’s courts. The “Mediar e Divino” (“To Mediate is Divine”) pilot project in the state of Goias, has started training evangelical pastors, Catholic priests, and Protestant ministers on the legalities of reconciling bickering parties and settling social squabbles.

Photo via Ollyy / Shutterstock.com

Your pastor doesn't have it all figured out. We promise.

They get scared. They get angry. They get lonely. And they doubt whether any of it's worth their time, or their faith.

giulio napolitano / Shutterstock

THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of Congo is one of the world’s poorest countries. In 2014, Congo ranked 186 out of 187 on the United Nations’ human development index—vying with Niger for the bottom of the list.

Yet Congo is extremely rich in soil, water, forests, and minerals. Diamonds, copper, gold, oil, uranium, and coltan are all mined, purchased, and traded from the DRC.

Coltan is the ore used in electronic devices. The so call “war of coltan” in the mineral-rich eastern Congo has left millions dead and more than a million women raped. Transnational corporations are able to exert extreme pressure on Congo’s weak government and economy. As a result, the country’s natural resources have become an important factor in increasing poverty and violence rather than wealth and development.

The Catholic bishops in Congo (about half of the country’s population is Catholic) repeatedly have denounced three specific kinds of evil: a climate favoring genocide, outbreaks of religious fundamentalism, and a push toward Balkanization.

Sébastien Muyengo, author of In the Land of Gold and Blood, is the Catholic bishop of Uvira in eastern Congo. As a result of the mineral wars, he writes, the country’s poverty has become a mental, human, and structural poverty, rather than predominantly material. Yet Congo has resources the rest of the world wants.

Some of you might be downright shocked to know that many clergy have to undergo a three-day battery of psych tests as part of the ordination process. If a significant issue is discovered, say, addiction or something else (perhaps the main reason these tests have become required), one's ordination process can be slowed down or halted all together. When I was going through the process, I too went through these evaluations.

The result? I have "a fragile sense of self."

What does this really mean? Well, I'm an alcoholic. It's true. I've spoken about it as part of my faith journey (read: testimony; yes, I have a testimony). I don't wave it around like some flag, but I'm not shy about telling people. And I have certainly told the congregations and other organizations I have served about my history with addiction.

Keeping this stuff secret, for me, is poisonous.

At any rate, there it was, "a fragile sense of self" on my evaluation. This caused everyone to pause. The ordination committee had a ton of questions for me. They did the obligatory background check (this is perfunctory; everyone gets one). They checked my references, etc. They did their due diligence to make sure, as best as anyone could, that I was not going to fall off the wagon.

Of course. No one can promise that. Not really.

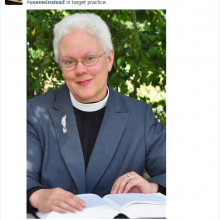

National Guard Sgt. Valerie Deant found mugshots of black men, including one of her brother, riddled with bullet holes at a police range in south Florida last month. After outraged critics drew attention to the police department, clergy across the country began to post photos of their own faces with the hashtag #UseMeInstead. The Washington Post explains why the hashtag began:

The effort was “motivated by our service to Christ and his call to love our neighbors,” Gonnerman told The Post.

“We initially started thinking if a whole lot of us, in our clergy collar and worship attire, sent our photos to them, it would make a really powerful statement,” Rev. Kris Totzke, a pastor in Texas, told The Post. “Then, it really snowballed, and we got people all over the country and of all different faiths.” …

“It’s such a desensitization thing, that if you start aiming at young black men, and told to put a bullet in them, you become desensitized,” Gonnerman said. “Maybe, to change the picture, it’s you know what, dare ya, shoot a clergy person.”

Following up on remarks to “60 Minutes” about the clergy sex abuse crisis and other controversial topics, Boston Cardinal Sean O’Malley has stressed that the Catholic Church needs a system to hold bishops accountable and must “avoid crowd-based condemnations.”

“We are all aware that Catholics want their leaders to be held accountable for the safety of children, but the accountability has been sporadic,” O’Malley wrote in a column posted Nov. 19 at the website of the archdiocesan newspaper. “We need clear protocols that will replace the improvisation and inertia that has often been the response in these matters.”

“Bishops also deserve due process that allows them to have an opportunity for a fair hearing,” he added.

O’Malley’s column was responding to both praise and criticism of his CBS interview broadcast Nov. 16 in which he said the Vatican needs to respond “urgently” to cases like that of Missouri Bishop Robert Finn, who remains in office despite a conviction in 2012 for failure to report concerns about a priest, the Rev. Shawn Ratigan, who was later convicted of federal child pornography charges.

The cardinal said Francis, who recently sent a Canadian archbishop to Finn’s diocese to investigate, was personally aware of the situation.

In the “60 Minutes” interview, O’Malley also called the Vatican’s investigation of American nuns a “disaster” and said if he were starting a church “I’d love to have women priests,” but he added that’s not what Jesus did. Both comments sparked strong reactions.

News articles about turmoil at General Theological Seminary had immediate impact on those of us who attended Episcopal seminaries.

But the news “went viral” far beyond that small coterie and for reasons beyond nostalgia.

For one thing, it’s a juicy soap opera. Faculty playing hardball, then finding themselves unemployed. A dean pushing back, then losing credibility as word about him spread. A board looking confused and high-handed. Students wondering if they, too, should go on strike.

But impact goes beyond the particular event itself. For something fundamental seems to be changing.

When I began a Masters of Divinity program at Wesley Theological Seminary, I was convinced that my generalized anxiety would be a wrinkle I’d iron out as I became more competent in preaching and pastoral care. What I failed to recognize was that my aptitude for ministry in itself was not the issue. I already felt called to hospital chaplaincy and had had experience working with the sick and dying as a nursing assistant. However, despite all the practical knowledge I’ve continued to gain at Wesley, anxiety has remained a debilitating problem.

When my anxiety was at its worst this past spring, I often asked myself, what business do I have pursuing ordained ministry? How can I serve others if I can’t take care of myself? Last week, regarding the suicide of Robin Williams, I heard frequently: “How can someone so funny do that?” The best answer I’ve found is that even when we are in great pain and anguish, feeling isolated from others, we don’t stop doing what we do best. Even in times of depression, and drug and alcohol abuse, Williams never ceased to do what he did best — make people laugh when they most needed to. Likewise, despite my anxiety, no matter how I attempt to close out the world, I still feel called to the ministry of chaplaincy, to bring healing to others through my presence.

I eat, sleep, and breathe faith and politics; it is my passion and calling. From 9-5 each weekday, I direct communications and advocacy for Sojourners, moving around Washington, D.C. for various meetings, engaging with reporters and the media, and planning advocacy strategies around pressing justice issues. Then I turn off my computer and walk out the door. But instead of going home, I’m usually off to another meeting that has little to do with politics and everything to do with faith.

I’m a bi-vocational pastor, and I spend 15-20 additional hours working in a local congregation alongside several clergy colleagues, who themselves are a mix of full-time and part-time ministers. Serving in a church keeps me rooted. It provides perspective when the dysfunctions of Washington threaten to consume me. Helping people discover faith and integrate it into their lives renews and enlivens my soul.

Part of me pretends that I’d be spending this much time worshiping on Sunday morning and hanging out with my fellow young adults anyway, so I might as well be polishing my ministerial skills. But when I’m honest, I know it isn’t close to the same thing. I am way more invested in people’s lives – their joys and concerns – and the life of a particular community than I otherwise would be as “just a member of the congregation.” It is a demanding role that can be emotional, mentally and spiritually draining at times, but I love every minute of it. This is what I was made to do. Being a pastor is my identity. This calling is fundamental to who I am and how I understand myself in the world.

The number of bi-vocational ministers is increasing rapidly. Many pastors who work full-time jobs and serve in congregations part-time receive little or no pay for their church service. This trend has been described as “the future of the church” and extolled because the model is a return to “the original church” that will “enliven congregations.”

Paul said, "the foolishness of the cross" not "the stable middle-class lifestyle," if you want my opinion on seminary education, the changing economy, and baptismal identity in general. We bear a responsibility to care for one another as Christians (and beyond) that we have abdicated to the persnickety "marketplace." It's time to talk about holy poverty again, I think.

I can hear my free church friends and colleagues now, "But we don't take a vow of poverty!" It's true. We don't. We remember this historical movement away from the monasteries and the cathedrals, the parish system and the state church. This is an issue of ecclesiology, no question. What I wonder, however, is if in our attempts to not fall into the traps of the past, we simply have settled on the marketplace as our model for ecclesiology. I assume we have.

My degree is a "professional degree," yet within its conceptual framework the notion that I am "professed" is easily lost. I am not called to earn, but to labor, to serve. My work is "worth" nothing. Instead, it is a response to a vocation that in many ways we all share. The wealth of the community affords me the opportunity to respond to that shared call in a particular way. I am not your employee. I am your pastor. I am poor. Any wealth I may posses comes directly from the pockets of others.

The contemporary fast-paced, capitalistic, U.S. free market society has lost the traditional commitments to and comprehension of ‘church.’ Our parents and grandparents understood church as a community to which they belonged. Church was a place where many aspects of social life happened. The pastor was hired by the church people to care for and nurture the community, both individually and collectively. People looked to the pastor for spiritual inspiration, ethical guidance, sound counsel, and pastoral care. The pastor was an extended member of the family and people were happy to make a personal financial contribution to pay the pastor's salary and to keep the church building in repair. Somewhere along the line our society ‘outgrew’ this version of church.

A recent article in The Atlantic titled "Higher Calling, Lower Wages: The Vanishing of the Middle-Class Clergy" laments the shift away from the traditional model of financing church and clergy as well as the increased costs for training clergy. The average Master of Divinity student (the degree for pastoral training) graduates with tens of thousands of dollars in student loans — sometimes entering into the six-digit category. According to the U.S. department of labor, the median wage for a pastor is $43,800 — not a salary that lends itself to paying off high-end loans.

Religious leaders from across Africa and England came together Wednesday to discuss the role clergy should play in preventing and responding to sexual violence.

The panel was part of the three-day Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict co-chaired by Angelina Jolie, the special envoy for the U.N. high commissioner for refugees. Jolie made an unannounced appearance before the event, causing attendance to surge and preventing several dozen participants from entering the crowded conference room.

In a pre-recorded video message, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby started the session by describing some of the positive developments he observed firsthand on a recent trip to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Historically there has been a culture of impunity,” he said. “Faith leaders are challenging that culture fiercely and saying that rape and sexual violence in war is absolutely unacceptable and will result in consequences.”

In his strongest personal remarks yet on the clergy sex abuse scandal, Pope Francis on Friday asked forgiveness “for the damage” that abusive priests have inflicted on children and pledged that the Catholic Church “will not take one step backward” in efforts to address the crisis.

“I feel compelled to personally take on all the evil that some priests — quite a few in number, though not compared to the total number — and to ask for forgiveness for the damage they have done by sexually abusing children,” Francis said.

“The church is aware of this damage,” he said. “It is personal and moral damage, but carried out by men of the church. And we do not want to take one step backward in dealing with this problem and the sanctions that must be imposed. On the contrary, I believe that we have to be very firm. Because you cannot take chances with children!”

North Carolina’s weekly protests against Republican-backed legislative initiatives last year brought thousands of people to the state Capitol in Raleigh each Monday chanting, “Forward together, not one step back.”

Now the movement is ready to reprise its demonstrations, which recall the tactics of the civil rights era.

The Rev. William J. Barber II and his Moral Mondays team are making final preparations for the kickoff event, dubbed the Moral March, scheduled for Saturday. Barber hopes it will be bigger than the Selma march for voting rights in 1965 that drew 25,000 people.

Today churches are often rocked with sexual harassment and abuse perpetrated by priests and clergy. Yet, sexual harassment and abuse to clergy, specifically clergywomen, is often swept under the rug.

A 2007 study by the United Methodist Church on sexual harassment and abuse found that nearly 75 percent of Methodist clergy women have experienced sexual harassment and abuse. The common settings for such harassment are church meetings and offices where perpetrators are mostly men and increasingly laity. “Sexual harassment destroys community. This alienating sinful behavior causes brokenness in relationships,” the study states.

Despite the prevalence of increased boundary training and education, the 2007 study found that only 34 percent of small churches and 86 percent of large churches have policies to handle such situations.

In 30 years of ministry, diaconal and ordained, I have seen that church politics, ignorance of or lack of policies and procedures, tolerance for inappropriate behavior, status of perpetrator, and money are obstacles to dealing with sexual harassment and abuse to clergy in a healthy way.