Church

On Aug. 17, three members of the Russian feminist punk band/performance art group Pussy Riot received the verdict in the criminal case against them: Guilty of "hooliganism" motivated by "religious hatred." Each was sentenced to two years in prison.

As a faith-based community organizer, I spend a great majority of my time trying to get political issues into the church so that the gospel can be relevant to the reality of those on and off the pews.

Therefore, I believe the best place for a “pussy riot” is the church. Although this may seem sacrilegious, here's why:

1. When the church ignores social and political issues it silently blesses injustice. (See slavery, the Holocaust, lynching, and child sexual abuse.) Testimony Time is a set time in many Black Churches when congregants can speak of their pains and triumphs and how God brought them through.

Testimony time is democratic and a time of raw honesty. I call what Pussy Riot did protestifying because they protested by testifying about the political conditions of their country.

Editor's Note: This is the sixth and final installment of Presbyterian pastor Mark Sandlin's blog series "Church No More," chronicling his three-month sabbatical from church-going.

They say you can never go home again.

The thinking is that, having left and experienced new things, you have changed and the people back home have continued in their lives just as you left them. Your experience of going back home again necessarily will be very different from your experience of home as you remember it, even though it may have changed very little.

In many ways, Church is one of my homes and I left it. I walked away for three months and experienced a bit of life outside of it. The three months are up and I'm going back home. This coming Sunday (Sept. 2) will be my first Sunday back.

The saying “you can't go home again,” probably originated from Tom Wolfe's novel, You Can't Go Home Again. It's the story of an author who leaves his home, writes about it from a distance and then tries to go home again. It doesn't exactly go well. The folks in the town are none-too-happy about him airing their dirty laundry so publicly.

So, you can't go home again? Well, I'm going to try.

The economy continues to weigh on pastors, with a new survey showing that nearly two-thirds say it has affected their churches negatively.

LifeWay Research asked 1,000 pastors about the economy’s effect on their churches and found that 56 percent described it somewhat negatively and 8 percent very negatively. Nine percent reported a positive effect on their churches and one-quarter said the economy was having “no impact on my church.”

“Pastor views on the economy are similar to many economic outlook surveys,” said Scott McConnell, director of LifeWay Research, which is affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention. “We weren’t surprised the current perspective of economic impact on churches is predominantly negative.”

RIDGEWOOD, N.J. — The parents of Tyler Clementi have left their longtime evangelical church due to its views on homosexuality.

Jane and Joe Clementi told The New York Times that they had grown increasingly out of step with the Grace Church, a nondenominational evangelical church in Ridgewood, N.J., due to its casting of homsexuality as sinful.

Tyler Clementi committed suicide by jumping off the George Washington Bridge in 2010. His death came just days after his roommate, Dharun Ravi, had spied on him during a tryst with another man in their freshman dormitory at Rutgers University.

Ravi was convicted of 15 charges, including invasion of privacy and bias intimidation, in March. He was sentenced to 30 days in jail, of which he served 20.

The case garnered national attention from the media, as well as gay rights and anti-bullying activists. Clementi had come out to his parents just days before he left for college, and numerous news outlets reported that he had left feeling rejected. According to the Times, Tyler told his mother that he did not believe he could be Christian and gay.

Mars Hill Bible Church has appointed a new teaching pastor, months after founding pastor and well-known author Rob Bell departed for California.

In an email sent on Wednesday to members of the Grandville, Mich., church, leaders announced Kent Dobson had accepted the lead position.

Dobson served as a worship director in the church’s early days and has preached as a guest speaker in the months since Bell left. He is the son of Ed Dobson, pastor emeritus at Calvary Church in Grand Rapids.

As I was driving today I had the radio on scan. It filtered through the stations skipping to the next station automatically. Station after station came and went. I finally stopped it on a talk show.

I listened for a time as the host was telling anyone who would listen including me that our country is moving full steam ahead in the wrong direction. He predicted the worst and called Christians to rise up and reclaim our nation.

This was not the first time I have heard such fear mongering. Not too long ago someone warned me that our government would soon “come after churches that don't toe the party line.” Another told me that our government was out to destroy the Christian faith. I think this sounds great.

Editor's Note: This is the fourth installment of Presbyterian pastor Mark Sandlin's blog series "Church No More," chronicling his three-month sabbatical from church-going. Follow the links below to read his previous installments, beginning in June.

- Church No More: Part 1 — Walking Away From Church

- Church No More: Part 2 — Church That Doesn't Steal Your Joy

- Church No More: Part 3 — The 'C' Word

- Church No More: Part 4 — I Don't Want to Go Back

A little over two months ago, I decided I'd spend my three-month sabbatical not going to church. Which might seem like a perfectly normal thing to do – except that I'm a minister. I've had some strange and wonderful experiences which I've written about, but possibly more strange and more wonderful than the experiences are the responses I've received.

From the very beginning the most frustrating response I get is not folks telling me I'll lose my faith if I leave church (and they have), or the ones telling me I can't begin to understand what it's like to be Spiritual But Not Religious (SBNR) in three short months (lots of those were also disturbingly aggressively worded), but rather the ones that say, “Oh, 'sabbatical!' Thanks. Now I have a word to call what I do! I stopped going to church years ago.”

“No!” I'd think while unsuccessfully trying to figure out how to reach through my laptop screen and shake some sense into them, “You are not on sabbatical! The sabbatical I'm taking about has to do with taking a rest, not leaving. It's rest and recuperation — communion with God in a way that is restorative. It's not about leaving! Sheesh.”

More than two months into my sabbatical, I now have to say, “Boy was I wrong.” They are on sabbatical, more so than I am.

Right there, in the middle of piles of fried chicken and biscuits, campers broke out in song, complete with choreography. Suffice it to say it’s simple enough and cumulative in its themes so that pretty much anyone can get the idea within a verse or two.

We keep talking about the changing face of church and how ministry is going to look different going forward; what if this is it? Not that I expect this is “the” model for how to do church from here forward, but there’s something to this “flash mob” concept, breaking out spontaneously into something that draws others in, right here, right now, where we are.

But we might get weird looks. We might even get in trouble.

Last Sunday, the Catholic singer/songwriter/poet/theologian Pádraig Ó Tuama (who hails from County Cork, Ireland), took to Revolution NYC's "barstool pulpit," to share stories, poems, and wisdom from the spiritual journey — his, yours, ours.

Listen to Ó Tuama's talk inside the blog ...

Does anybody else feel this weight?

I woke up this morning in tears. I don’t know why today is different, but I do know the weight is for my brothers and sisters who are in pain.

I imagined what the night was like for folks in my neighborhood who had to fend off threats last night.

I imagine the young girl in a car — against her will or against her first choice — with the guy named John, and I lament for her soul.

I imagine the young guy standing out all night selling death so he can have a little life — whether it’s in the form of food, dignity or just to feel like he is meeting some need, somehow.

I imagine the mom lying in the bed next to someone she would rather not touch, but because he pays the bills for her kids to eat and sleep, she puts up with his abuse and doesn’t say anything about the other woman he also lies with around the corner.

I love the Church. I have literally been going to church my whole life — that is, until two months ago.

Then I stopped cold turkey. You can read about it in my post "Walking Away From Church."

Masses of people responded. It astounded me. Most ministers expressed concern saying things like, “My Brother, I am worried that you may be on a dangerous journey,” or, “I fear you may lose your faith.”

Frankly, what I heard them saying was, “Faith is so fragile it needs the Church to enforce it,” which only made me more certain I was making a remarkably healthy spiritual choice.

Former church-going folk frequently told me things like, “There is a large disconnect between the 'Church' of today and the teachings of Jesus,” and “I have found God in a dynamic, deep way and I love God so much more and for real now than when I was unwittingly trying to fit in with my church culture.”

I've been away from church for two months now and I have to say, I am more at peace than I ever have been. My faith is stronger than it ever has been. My family life is healthier than it ever has been. My desire to seek out God and follow the teachings of Jesus is stronger than it ever has been.

I do not want to go back to Church because life outside of Church is better. It just is. There's no dogma complicating the path to God. It is more than refreshing to escape the games church-folk play with the intent of establishing control and “rightness” on their part; it is life-giving to escape it.

Growing up, I heard things at camp and in youth group about how “the world” thought and acted one way, and how “we” were not like that. In fact the world, it seemed, was intent on unraveling everything I valued as good and true, leaving me with a smoldering pile of ideals and beliefs, all dead at the point of a secular sword. It was our job as Christians not only to defend against this frontal attack, but also to fight back in an effort to win souls for the Kingdom.

It was an epic battle, now in its beginning stages, but that would play out as depicted in the fantastical, horrifically violent pages within the Book of Revelation. The end is near; which side will you be on?

The Christianity of my youth was much like the Temple Mount in Jerusalem — a shining jewel high on a hill, beset on all sides by forces intent solely on its destruction. And our mission, as stewards of the faith, was to preserve and maintain the faith, protecting it at all costs. This, I would later learn, was the theological heart of what I now know as the Culture War. And some within the walls of the temple might argue I’ve abandoned the cause, or perhaps switched sides all together.

Recently, Keith Anderson, my friend and co-author on Click 2 Save: The Digital Ministry Bible, wrote a post that’s been stirring a good deal of interest — and concern — across the blogosphere.

Anderson’s piece, “What Young Clergy Want You to Know,” has, I suspect, attracted so much attention because it dives right into the middle of the frustration, anxiety, and discouragement one increasingly finds among clergy of all ages and levels of experience, but that is amplified among younger clergy because they’ve made a vocational commitment to the Church at a time when such a choice seems crazier than ever.

This, as Anderson points out in the post, is because younger clergy “understand they are presiding over the death of American Christendom.”

Younger clergy, says Anderson, “are worried about job security — not just about getting paid (which is not always a given) — but whether they can do the job they feel called to do in congregations that don’t want to change.” He continues, “Being prophetic is an attribute we laud in seminary, but it can get you fired in the parish.”

Well, there you have it. The unvarnished truth of vocational experience in institutional contexts that over time wears out even the most patient, most tolerant, most enthusiastic of clergy. The wrenching responses to the post make clear that Anderson struck a nerve among his clergy colleagues.

Conservative commentators like Rupert Murdoch's stable and Ross Douthat of The New York Times are feasting on what they perceive as the "death" of "liberal Christianity."

They add two and two and get eight. They see decisions they don't like — such as the Episcopal Church's recent endorsement of a rite for blessing same-sex unions. They see declines in church membership. They pounce.

Such "liberal" decisions are destroying the church, they say, and alienating young adults they must reach in order to survive.

Never mind that surveys of young adults in America show attitudes toward sexuality that are far more liberal than those of older generations. Never mind that conservative denominations are also in decline.

Never mind — the most inconvenient truth — that mainline denominations began to decline in 1965, not because of liberal theology, but because the world around them changed and they refused to change with it.

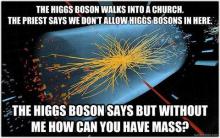

Thanks to Steve Knight for alerting me to this joke, which has become one of my instant favorites. After all, it combines two things I dig: nerd humor and theology (also nerdy).

Yeah, yeah, you may be groaning, but you’re smiling while doing it. Admit it.

There’s plenty of chatter lately about the so-called “God Particle,” recently discovered , with some in the scientific field actually calling it the “goddamn particle,” because (at least as I understand it) the discovery opens up the possibility of something without detectable mass actually giving mass to other particles.

Kind of like: In the beginning there was nothing, and then…

Sound familiar?

In recent days, conservatives have attacked the Episcopal Church. The reason? The church has just concluded its once every three-year national meeting, and in this gathering the denomination affirmed a liturgy to bless same-sex unions. Conservatives assert that the Episcopal Church's ever-increasing social and political progressivism has led to a precipitous membership decline and ruined the denomination.

Many of the criticisms were mean-spirited or partisan, continuing a decade-long internal debate about the Episcopal Church's future. However, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat broadened the discussion, moving beyond inside-baseball ecclesial politics to ask a larger question: "Can Liberal Christianity be Saved?"

The question is a good one, for the liberal Christian tradition is an important part of American culture, from dazzling literary and intellectual achievements to great social reform movements. Mr. Douthat recognizes these contributions and rightly praises this aspect of liberal Christianity as "an immensely positive force in our national life."

Despite this history, however, Mr. Douthat insists that any denomination committed to contemporary liberalism will ultimately collapse. According to him, the Episcopal Church and its allegedly trendy faith, a faith that varies from a more worthy form of classical liberalism, is facing imminent death.

Learning to speak as a Christian is one of the most important and often ignored aspects of our discipleship. Nowhere is this fact more obvious than when churches try to talk about politics. When the small group leader makes a disparaging comment about Mitt Romney’s Mormon faith, or a car rolls into the church parking lot with a “NOBAMA” bumper sticker proudly displayed, what do we do?

Is bumper sticker propaganda and negativity the best we have to offer?

Admittedly it can be risky to talk about politics in the local church. All it takes is one idea or statement that flies in the face of someone’s deeply held convictions and that could be the end of our influence and the end of that person’s involvement in our ministry.

Still, the upcoming presidential election will be the defining cultural event of the next six months. If we completely ignore it we are missing a golden opportunity for discipleship.

How can churches have a healthy conversation about politics in the middle of a national election without demonizing the opposition and causing disunity?

I’ve been working on this question for months now, and as part of my preparation I wrote a book called Public Jesus. Here’s a little bit about what I’ve learned in the process:

1) Love the One You’re With

I have a confession.

(That's rich, right? A minister confessing.)

I have a hard time telling people I'm a minister. Yes, really. I actually tend to handle it this way:

Person: “So, what do you do for a living?”

Me: “I'm a minister... (appropriate pause)... but not the kind you just pictured in your head.”

Sad, I know.

Honestly though, it's worse than that. I'm even very resistant to calling myself a “Christian.” And I'm not even close to the only Christian who feels that way! It's so bad that I have this very conversation with people all the time. There seems to be some kind of “Believer-like-me Radar” which tells people it's safe to talk to me about not liking the“C” word — CHRISTIANITY.

A new map has divided the country into red and blue ... but this one has nothing do do with politics or the upcoming election. No, we're not talking Republicans or Democrats; we're talking Church or Beer. (Do the two have to be mutually exclusive? What if you're Lutheran?)

FloatingSheep.org compiled geotagged Tweets from June 22 - 28 comparing the geographic concentration of convos regarding church and beer.