Recently, Keith Anderson, my friend and co-author on Click 2 Save: The Digital Ministry Bible, wrote a post that’s been stirring a good deal of interest — and concern — across the blogosphere.

Anderson’s piece, “What Young Clergy Want You to Know,” has, I suspect, attracted so much attention because it dives right into the middle of the frustration, anxiety, and discouragement one increasingly finds among clergy of all ages and levels of experience, but that is amplified among younger clergy because they’ve made a vocational commitment to the Church at a time when such a choice seems crazier than ever.

This, as Anderson points out in the post, is because younger clergy “understand they are presiding over the death of American Christendom.”

Younger clergy, says Anderson, “are worried about job security — not just about getting paid (which is not always a given) — but whether they can do the job they feel called to do in congregations that don’t want to change.” He continues, “Being prophetic is an attribute we laud in seminary, but it can get you fired in the parish.”

Well, there you have it. The unvarnished truth of vocational experience in institutional contexts that over time wears out even the most patient, most tolerant, most enthusiastic of clergy. The wrenching responses to the post make clear that Anderson struck a nerve among his clergy colleagues.

But clergy are not, of course, alone in these feelings. So, too, are lay leaders and lay people more generally, who are struggling to remain faithful to a Church that is often decades out of touch with the spiritual needs and interests of its people.

And, among young people who don’t muster the wherewithal to claim a place in the church by clerical vocation, the story is even grimmer. They have simply voted with their feet, spending their Sunday mornings hiking or cycling with friends, hanging out with their pets, and exercising their commitment to social justice by participating in one of the greatest decades of volunteerism in American history.

These are all things that young adults tend to find deeply spiritually meaningful for which there often seems no space in most churches.

For the past year or so, I’ve been speaking with clergy and lay leaders across denominations about the ways in which the world is changing and what that might mean for churches. I tend to begin these conversations with these stark facts from the Pew U.S. Religion Landscape Survey:

If current trends continue:

- 32 percent of young people raised as Roman Catholics will leave the denomination

- 54 percent of young people raised as Evangelicals will leave the faith family

- 55 percent of young people raised as Mainline Protestants will leave the faith family

And then, I generally say this: Our kids are leaving our churches not because of something “out there,” not because of “the culture,” but because we are teaching them in our churches that faith is unimportant in everyday life, that religious identity is private and largely decorative, and that religious commitment is mostly about being nice and feeling good about oneself and others.

This last bit I draw mainly from the work of Kenda Creasy Dean, whose starling book Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers is Telling the American Church should be required reading for every lay and ordained leader in every church.

Dean advances the work of Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton, whose work with data from the National Study of Youth and Religion revealed a bland, feel-good, and ultimately forgettable version of Christianity offered up by most Catholic and Mainline Protestant churches. Dean contrasts this “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” with a “consequential faith” grounded in a sense of authentic mission, sacrifice, and radical compassion.

But “consequential faith” is of course also consequential for congregations, who must make space available for kids, teens, and young adults to take up new ways of doing church and new ways of serving God in the world in communities largely shaped and governed by people who are just fine with the way things are — which is often the way they were in 1952. So, as we’re all too well aware, our young people just fade away.

I have to tell you, as much as I really do love talking with people in church communities around the country, it is six kinds of no fun to look into the faces of a room full of people in their 60s and 70s and tell them that the ways they have come to love and find comfort in the church don’t work for many of the rest of us. These are lovely, faithful, caring people who have often worked very hard to create the churches that remain today.

They’ve given generously, as we say, of their time, talent, and treasure, and it has to be a bitter pill to be told, in essence, “thanks, but no thanks” to a lot of the way the experience of church is currently structured and enacted.

Indeed, I confessed to a group a few weeks ago that I often wished I were one of those folks offering glowing example after glowing example of thriving Mainline communities or promising that a new emergence of church was just around the corner. There are thriving churches across the country, but we all know that they are not the norm. And, certainly, something new is emerging from among the disparate beliefs and spiritual practices swirling among the under-sixty set.

But it’s not likely an emergence or an awakening that will find its way back to the valuable networks of built churches in neighborhoods around the United States and across the world. Rather, without a structure to support all the spiritual energy floating around the cosmos — and there remains much of it — it seems likely to swirl off into the ether, never fully channeled into the work of kingdom-making on earth to which God calls us.

For those of us in the generational in-between — no longer “young adults” in anyone’s imagination, but not much a part of the now-traditional structure and practices of the church — this is a particularly frustrating time. We want to open the doors to younger people, to turn over the liturgy, the music, and the priorities for service to them. But we also want to honor the gifts of our elders, to listen to their voices and value their wisdom as we work together to allow whatever might emerge to do so as the Spirit will have it do.

We’re stuck, many of us, between our kids and our parents. We understand, on the one hand, how alienating all the male god-talk of the church and the seemingly endless roiling about LGBT people is for almost anyone under 40. On the other hand, we grew up hearing our parents say “hallowED be THY name” when they prayed the Lord’s Prayer, so the stilted pronunciation offers a certain nostalgic comfort to us as well.

For those of us in lay or ordained leadership, the stress of trying to please everyone, or the difficulty of being honest about what we know really must change with people we truly love and admire, often sucks the spiritual life out of worship and church community for us. We continue because we feel that we must, but sometimes it’s difficult to know exactly why or to what end.

“I feel completely spiritually dry in church,” a woman in her late 40s said to me recently. “And yet I feel that this is the richest time spiritually in my life. My kids are on their own now, and I’m able to explore my own spirituality and serve based on where I feel most called in ways I never could before. I don’t want to do that on my own. I want companions, fellow travelers. But I’m just not finding that at church—in the choir, in the bible study group, on the grounds committee. That’s just not where I am spiritually. Am I really alone in this?”

I suspect she isn’t. I suspect that there are too many of us, lay and clergy alike, who want more from the experience of church. We want it to be consequential — to make demands of our lives, to work us over, to renew us as friends of God and servants of God’s people. And, we don’t so much want to be presiding over the death of American Christianity as participating in its renewal as well.

Many years ago, the poet Adrienne Rich, wrote about poetic “awakening” happening as a startling act of renewed imagination. For this renewal to happen, she wrote,

there has to be an imaginative transformation of reality which is in no way passive. And a certain freedom of the mind is needed — freedom to press on, to enter the currents of your thought like a glider pilot, knowing that your motion can be sustained, that the buoyancy of your attention will not be suddenly snatched away. Moreover, if, the imagination is to transcend and transform experience it has to question, to challenge, to conceive of alternatives, perhaps to the very life you are living at that moment.

Those of us who are “stuck in the middle” don’t have to remain so. If you’re over 30 and under 60, your “in between” status gives you a unique perspective on what ails and what might help to renew the church.

Now is the time to share your experience, insight, and imagination.

What do you see as the alternatives to the very life we are living as a church right now?

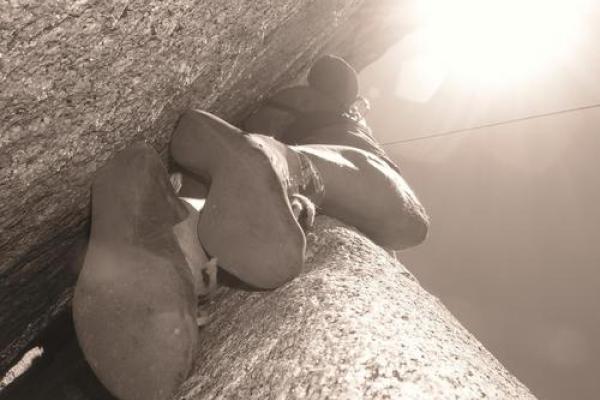

What might we be able to grow between the rock and the hard place in which so many of us find ourselves in the church these days?

Elizabeth Drescher teaches religion and pastoral ministries at Santa Clara University. She is the author of Tweet If You ♥ Jesus: Practicing Church in the Digital Reformation (Morehouse, 2011) and, with Keith Anderson, Click 2 Save: The Digital Ministry Bible (Morehouse, 2012). She was recently awarded a journalism grant from the Social Science Research Council and the Templeton Foundation to study prayer practices among religious nones. Read more from Elizabeth on her website, ElizabethDrescher.com, where this post originally appeared.

Image: By Joy Stein/Shutterstock.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!