Church

FOR SERIOUS AND chronic mental illness, there is no cure—short of a miracle. There is no “all better.” Even when well managed, such illness is a lifelong reality, and relapses can happen without warning. Even for episodic illness, the road to health can be long and mountainous. Walking alongside someone with mental illness may mean a lifelong hike over peaks and valleys, learning to grow in faith and in relationship with Jesus through an illness that clouds the view. That walk might cause mistrust of reality and of a person’s own thoughts. It might require extra patience for processing truth. It might repeatedly tax the resources of the church and its fellowship. And churches, like other organizations, grow tired of such taxation. Culturally, we expect people who fall down to pull themselves back up and put their hands to the plow. Sure, everyone stumbles occasionally. And we’re willing to give help in times of crisis. But when that time of crisis doesn’t seem to end, we start to wonder why we’re still helping. Why we’re not seeing progress. Why we’re not moving on.

The father of a son with bipolar disorder spoke passionately from his experience:

Attitudes have to change. This doesn’t go away. … that’s the issue that anyone with mental illness or anyone who is going to minster to mental illness is going to eventually wade into. Wait a minute. We helped you with this a year ago, two years ago. The problem is like telling a diabetic, “We helped you with your blood glucose a year ago.” Yeah, but guess what. They’ve got to do this every minute of the day until they die. So that is a daunting task … it has to fall to the whole body of Christ, because it’s only the body that can handle something like that for a lifetime.

THERE IS STILL a political definition of “Christian” out there that is depressingly familiar: the right-wing voting, Fox News-sourced agitprop spewer who uses Jesus to shoehorn others into something the actual Lord of the universe could care less about. Lillian Daniel is not going to take this definition anymore, but she’s not mad as hell. She’s winsome as heaven. Her humor clears the way for her preaching to hit home, and her love for the church, both her congregation and universal, anchors this work. Give it out to your friends and to strangers on the street.

First, Daniel’s humor: It is hard to give examples of her humor without them falling flat. She’s at her droll best when the reader’s defenses aren’t up. This isn’t the humor of the warm-up act before the preacher gets on to something serious—she often drives her meatiest points home with her funniest stuff. For example, a running motif in the book is the airplane companion who thinks he’s being edgy when he says to the pastor beside him that he sees God in rainbows and sunsets. This “spiritual but not religious” mindset is now the bland norm in America, not some spectacular new revelation: “They are far too busy being original to discover that they are not.”

Some of Daniel’s most withering observations are reserved for the mainline church she loves: the sneering religious critic is told “all those questions actually make him a very good mainline Protestant.” The self-congratulatory short-term missionary who comes home convinced how “lucky” she is to live in America receives this barb: “When generosity begets stupidity it wasn’t really generosity to begin with.”

Making an ultimatum about church attendance to a sleep-deprived teenager may be my own version of hell on earth.

“We are leaving for church in 10 minutes,” I said, summoning my most authoritative voice before the lifeless lump under the covers.

My seven-year old Annie Sky watched the tense exchange between me and my 14-year old daughter Maya, who made periodic moans from the top bunk. With furrowed brow, my first grader sat on the couch, as if observing a tiebreaker at Wimbledon with no clear victor in sight.

For a moment, I wondered why I had drawn the line in the Sabbath sand, announcing earlier in the week that Maya would have to go to church that Sunday morning after an all-day trip to Dollywood with the middle school band. Somehow I didn’t want Dolly Parton’s amusement park to sabotage our family time in church. (The logic seemed rational at the time).

When Maya lifted the covers, I glimpsed the circles under her eyes and sunburn on her skin. But I repeated my command, with an undertone of panic, since I wasn’t sure if I could uphold the ultimatum.

When she finally got into the car, I breathed deeply and turned to our family balm, the tonic of 104.3 FM with its top 40 songs that we sing in unison. As the drama settled, I realized one reason why I made my teenager go to church: I want my daughters to know that we can recover from yelling at each other (which we had) and disagreeing. We can move on, and a quiet, sacred space is a good place to start.

Life is difficult. It can knock you down. Sometimes, an entire nation gets knocked down.

First it was Boston. Some mad man (or men) lays waste to one of America’s most hallowed sporting events — the Boston Marathon. Sidewalks that should have been covered with confetti were covered in blood.

Then it was the quintessential small Texas town of West. Populated by hearty Czech immigrants, folks in West worked hard in their shops, bakeries, and fertilizer plant until the plant exploded. A magnitude-2.1 on the Richter scale, witnesses compared it to a nuclear bomb. Dozens are feared dead.

In the nation’s capital, we had the bitter realization that something is broken that will not be easily repaired. A commonsense proposal that emerged from the Newtown, Conn., tragedy, background checks to prevent convicted felons and the seriously mentally ill from purchasing guns online or at gun shows, fell prey to Washington gridlock. None of the Newtown proposals — the ban on assault weapons, limits on the number of bullets a gun can hold or expanded background checks — could garner the 60 votes necessary to overcome a Senate filibuster.

Finally, there were the ricin-laced letters sent to a Republican senator and the president.

We have a group at our church that does a weekly sandwich ministry together. Though we already had a group that makes sandwiches each week for a local shelter, another team realized some folks don’t go to shelters, and that they might be missing out on a real opportunity to connect with different folks in our community if they didn’t go out to where the people are.

So now, every week, they walk the streets of downtown Portland and hand out upwards of 100 sandwiches. As they’ve met folks who live outside, they’ve identified other needs some have, such as socks, new underwear, rain gear, flashlights, and batteries. Each week, they come back with a list of needs, and each week our congregation helps fill those needs.

To me, this kind of ministry is exemplary of what missional church is about. We don’t simply wait behind the walls for people to come ask for something; we go out, meet people face-to-face and get to know them. Yes, we offer them a meal, but we also share stories, learn a bit of their history, and they come to know that there actually are flesh-and-blood people behind all those steeples and stone facades.

When it comes to running, America often looks like a country divided between apostles and apostates.

For true believers like Olympian Ryan Hall, marathons assume an almost-biblical importance.

“I have heard stories and had personal experiences in my own running when I felt very strongly that God was involved,” Hall, an evangelical Christian, has said.

Other Americans — athletic atheists, you might call them — roll their eyes and see marathons as a painful waste of a perfectly nice day.

In the Church of Running, I sit somewhere in the back pew.

HOUSTON — Sunday mornings at Houston Oasis may look and feel of a church, but there’s no cross, Bible, hymnal, or stained glass depictions of Jesus. There’s also nary a trace of doctrine, dogma, or theology.

But the 80 or so attendees at this new weekly gathering for nonbelievers come for many of the same reasons that others pack churches in this heavily Christian corner of the Bible Belt — a sense of community and an uplifting message that will help them tackle the challenges of the coming week, and, maybe, the rest of their lives.

“Just because you don’t believe in God does not mean you do not need to get together in community and draw strength from that,” said Mike Aus, a onetime Lutheran pastor who is now an atheist and founder of Houston Oasis.

“We are open to any message about life as long as no dogmatic claims are made.”

Fifty years after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. challenged white church leaders to confront racism, an ecumenical network has responded to his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“We proclaim that, while our context today is different, the call is the same as in 1963 — for followers of Christ to stand together, to work together, and to struggle together for justice,” declared Christian Churches Together in the USA in a 20-page document.

The statement, which is linked to an April 14-15 ecumenical gathering in Birmingham, Ala., includes confessions from church bodies about their silence and slow pace in addressing racial injustice.

“The church must lead rather than follow in the march toward justice,” it says.

As has happened many times after I have given a talk about the Body of Christ’s responsibility to care for their brothers and sisters experiencing impoverished and dehumanizing conditions, I was asked to answerthose questions — the ones in my experience that are always the first to be asked the moment I stop speaking.

“How will I know I have given enough? How does the church balance financial responsibility with service to the poor? Where do we draw the line?”

These questions always come, sometimes spoken in a curious tone by a person whose heart is being convicted, sometimes in an angry accusing tone insinuating I must hate prosperity, sometimes privately as a whisper in my ear or in a personal email filled with insinuations about my sanity. What a preposterous proposal, that the Body of Christ in any particular location should be the first resource to its own community for spiritual, physical, and emotional well being! Don’t I know that such a mission is naïve and impossible to achieve? Most recently it was phrased like this: “I love this idea, but it is difficult to see benevolence funds go towards someone's electric bill when they smell like they smoked five packs of cigs before meeting with us; what do we do?”

Church is being reinvented. So are technology and education. And all for the same reasons.

Facebook just started moving Google’s cheese with its launch of Home. An army of upstarts in Silicon Valley is challenging the hegemony of Microsoft. Nothing is staying the same; disruption is the path to prosperity.

The reason: the marketplace is highly dynamic. New needs emerge. New products stimulate new needs. New entrants want to make a difference right away. Problems and opportunities multiply faster than bureaucratic pillars can respond.

ANYONE WHO LIVES in Christian community or participates in congregational life knows that it is a holy mess. A group of flawed individuals trying to do "life together" can bring out the worst in one another. But that's precisely where God calls us to be.

In our hyperindividualistic culture, it's often difficult to remember that God has created us to be in community. Christian faith and discipleship, from the beginning, have been shaped not by going at it alone but by engaging in ancient and contemporary communal experiences. The first house churches and the formation of communities among the early desert fathers and mothers, as well as today's megachurches, parachurch organizations, and new monastic groups, all point to how we long to be connected to God and with one another.

Our faith and character are refined by the miraculous gifts of grace, reconciliation, and forgiveness made available to us in community. In such a demanding and disconnected world, it is indeed a miracle when two or more gather to break bread and give of themselves in service to God and one another.

Here are some books to help us along the Way, as we seek to deepen our understanding of what it means to be in communion with Christ and with each other.

In 2009 I was co-leading a new intentional community in Washington, D.C. Our nascent group endured many struggles, including interpersonal issues, conflicting visions and goals, and the involuntary removal of a community member. How I wish The Intentional Christian Community Handbook: For Idealists, Hypocrites, and Wannabe Disciples of Jesus (Paraclete Press), by David Janzen, was available when we first began our journey.

Pope Francis on Wednesday said women play a “fundamental role” in the Catholic Church as those who are mostly responsible for passing on the faith from one generation to the next.

While the new pope stopped far short of calling for women’s ordination or giving women more decision-making power in the church, his remarks nonetheless signaled an openness to women that’s not often seen in the church hierarchy.

“In the church and in the journey of faith, women have had and still have a special role in opening doors to the Lord,” the Argentine pontiff said during his weekly audience in St. Peter’s Square.

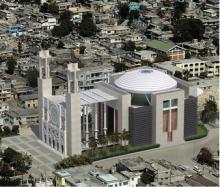

WE WERE LOOKING at cathedrals while others were mourning and burying their dead.

It was the first day of the international design competition that would help choose a few architectural plans that might be used to rebuild Notre Dame de l'Assomption, Our Lady of the Assumption, Port-au-Prince's most famous cathedral. This cathedral was so central to the city that, before it was leveled in the Jan. 12, 2010, earthquake, its turrets could be seen from most places in Port-au-Prince, as well as from the sea, where mariners used a light on the cupola of the church's north tower to help bring their ships home.

During the 2010 earthquake, the Catholic archbishop of Port-au-Prince, Monsignor Joseph Serge Miot, was killed inside an administrative building adjoining the cathedral, along with priests and parishioners. It was the images of their crushed bodies and their loved ones wailing around the perimeters of the cathedral's rubble that motivated me, a non-architect and non-Catholic—but a lover of cathedrals—to agree to join a development strategist, a preservationist architect, a structural engineer, a priest and liturgical consultant, the dean and associate dean of two architectural schools, and the editor of a magazine that discusses the dual issues of faith and architecture to help select three out of the 134 moving, elegant, and in some cases totally out-there designs that we had received from architects all over the world. Among the panelists, three of us were Haitian born, and many of the others had either worked in Haiti or in the Catholic Church for years.

The selection exercise itself was one that mirrored faith, blind faith. We were looking at sketches and plans but had no idea who had designed them. Some of the entries contained written statements that were so moving in their optimism for Port-au-Prince and its 3 million inhabitants, their hopes for Haiti and her people, and their longing for the rebuilt cathedral to serve as a symbol of renewal that they nearly brought me to tears.

THE CHURCH IS locked in a polarized debate around same-sex relationships that is creating painful divisions, subverting the church's missional intent, and damaging the credibility of its witness. We've all heard the sound-bite arguments. For some, condoning or blessing same-sex relationships betrays the clear teaching of the Bible, and represents a capitulation to the self-gratifying, permissive sexual ethic of a secularized culture. For others, affirming same-sex relationships flows from the command to love our neighbor, embodies the love of Jesus, and honors the spiritual integrity and experience of gay and lesbian brothers and sisters.

The way the debate presently is framed makes productive dialogue difficult. People talk past one another. Biblical texts collide with the testimony of human experience. The stakes of the debate become elevated from a difference around ethical discernment to the preservation of the gospel's integrity—for both sides. Lines get drawn in the ecclesiastical sand. Some decide that to be "pure" they must separate themselves spiritually from others and break the fellowship of Christ's body. Then the debate devolves into public wrangling over judicial proceedings, constitutional interpretations, and property ownership. Meanwhile, the "nones," those who are walking away from any active relig-ious faith, find further confirmation for their growing estrangement.

Mirroring the dynamics of contemporary secular politics, the debate is driven by small but vocal minorities with uncompromising positions at one end or another of the spectrum. For the majority in the middle, who may be unclear about their own understandings, exploring their questions is made difficult because of the polarized toxicity of the debate. Further, those in positions of leadership in congregations or denominations come to regard the controversy over same-sex relationships as the "third rail" of church politics. They don't want to touch it. I know this because I've been there myself.

The first Christmas after my daughter was born, I got a two-year membership to 24 Hour Fitness as a gift. Included in the membership was one personal training session.

My trainer bristled with annoyance at my “fad diet” when I told him we were going Paleo for three months. Then he showed me to the elliptical machine and told me that he lost weight by drinking sugar-free Kool-Aid all day and ordering off of the light menu at Taco Bell.

Obviously, our philosophies weren’t in line. But I was still able to get some cardio, weights, and an occasional spin class in at the gym. No hard feelings. But staying motivated and committed to working out while staying home with a toddler has been hard.

That might be because I haven’t tried CrossFit.

I think CrossFit is like secular church. It offers more than weight loss or fitness. It speaks to our innate desires for community, purpose, and transformation.

CLARKSVILLE, Tenn. — We did a focus group here as part of strategic planning at Trinity Episcopal Church.

Question: if you stood on the edge of your church’s property and looked outward, rather than inward as we usually do, what would you see?

A public school kindergarten teacher spoke about kids who come to school hungry and wearing shabby clothing. She started to discuss the family chaos her kids describe during sharing time, but she began to weep and couldn’t speak at all.

Life inside a bubble can feel complete, even dynamic, as the bubble’s surface shimmers and yet retains form.

When the surface is breached, the bubble collapses immediately, shattering into a liquid spray faster than a metal object can fall through where it used to be. What looked like a permanent structure is, in fact, uncertain and quickly lost.

We saw a ”tech bubble” burst 13 years ago. What had seemed durable and laden with value turned out to be vapor. The “housing bubble” came next. Some think another “tech bubble” is about to burst.

The bubble I see bursting is establishment Christianity in America. It is bursting ever so slowly, even as millions of people still find life, meaning, safety, and structure inside. But one failing congregation at a time, the surface of shimmering shape is being breached.

Bio: Executive director of Sexual Minorities Uganda, which works for full legal and social equality in the country, and recipient of the 2011 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award. www.sexualminoritiesuganda.net

1. What’s your response to the letter U.S. religious leaders signed last year, which condemned the “Anti-Homosexuality Bill” before Uganda’s Parliament because it “would forcefully push lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people further into the margins”?

Uganda is a very Christian country. About 85 percent of our population is Christian—Anglican, Catholic, and Pentecostal. So for religious leaders to speak out against the Ugandan legislation, that is very important for me and for my colleagues in Uganda, because it speaks not only to the politicians and legislators, but also to the minds of the ordinary citizens.

It is very important to have respected religious leaders involved, including Archbishop Desmond Tutu, because these are leaders who have spoken out on other human rights issues such as apartheid, women’s rights, and slavery. And for us, for the voice of LGBT rights, to join with these other issues clearly indicates that our movement is fighting for human rights.

OVER DINNER my friends and I reflected recently on the headlines that surprised us last year. A few were especially painful: former Rep. Todd Akin's comment that "legitimate" rapes do not lead to pregnancies; failed Senate candidate Richard Mourdock's comment that a pregnancy from rape is "something that God intended to happen"; and the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), in effect since 1994, ending as the 112th Congress closed without reauthorizing it. All reminded me why the second edition of The Cry of Tamar: Violence Against Women and the Church's Response, by Pamela Cooper-White, is still needed almost 20 years since its first edition.

The Cry of Tamar reads as a graduate textbook on providing pastoral support for the victims of violence against women. It weaves pastoral counseling methods and social and psychological theories in dialogue with biblical exegesis and constructive theology to give clergy, pastoral caregivers, and religious leaders tools to help victims of violence and the larger Christ-community.

The story of Tamar, a girl raped 3,000 years ago in Jerusalem, frames and guides the book's goal of providing healing to the girls and women who are victims of violence today.

Advocacy, prevention, and intervention to stop violence against women have advanced since the 1995 first edition. Religious communities and congregations have become more informed about how to care and respond to both victims and perpetrators. But the need for increased awareness and education is ongoing. This second edition is an effort to update the conversation and keep it on the table.

As the flu outbreak spreads across 48 states, some religious leaders are advising their flocks to take precautions, but others say avoiding infection is just a matter of common sense.

Several Catholic dioceses, including Manchester, N.H., Boston, and New York, are advising priests to consider not offering the shared chalice of consecrated wine at Holy Communion at Masses. Communicants would only receive the consecrated wafer.

In addition, Manchester Bishop Peter Libasci had other suggestions, reported The Eagle Tribune of North Andover, Mass.

“The faithful should be encouraged to share the Sign of Peace without touching hands or kissing,” he said. “This may be done with smiles and a bow of the head in reverence to one another.”