Books

Spirit Connections

Some Western and global South churches have established “sister church” relationships as a more mutual alternative to the old mission field approach. Drawing on fieldwork and interviews, Janel Kragt Bakker studies the give and take of this model in Sister Churches: American Congregations and Their Partners Abroad. Oxford

Border Clashes

The documentary The State of Arizona captures multiple perspectives on undocumented immigration in the aftermath of Arizona’s controversial Senate Bill 1070, dubbed the “show me your papers” law. Directed by Catherine Tambini and Carlos Sandoval, it will premiere on PBS’s Independent Lens series on January 14 (check local listings). communitycinema.org

Two of the world’s great libraries — the Vatican Library in Rome and the Bodleian Library at Oxford University — have scanned and loaded the first of 1.5 million pages of ancient Hebrew, Greek, and early Christian manuscripts online Tuesday.

The project brings rare and priceless religious and cultural collections to a global audience for the first time in history.

The website is the first step in a four-year project and it includes the Bodleian’s 1455 Gutenberg Bible — one of only 50 surviving copies.

The $3.3 million project is funded by the Polonsky Foundation, which aims to democratize access to information. Leonard S. Polonsky is chairman of Hansard Global PLC, an international financial services company.

How do you get kids to read one of the world’s oldest books? Ask Sally Lloyd-Jones, whose The Jesus Storybook Bible recently passed the critical mark of one million copies sold.

The British ex-pat and now proud New Yorker has never married or had children of her own, yet aims to retell the Bible to something that comes alive for young people.

One of her editors told her once that there are two types of children’s books authors: the ones who are around children, and the ones who are children inside.

“It kind of freed me, because I think I know I’m that second one,” she said. “And I can still write from that place, because my childhood is so vivid.”

Nearly every home has at least one Bible, although few read it.

But 16 percent of Americans log on to Twitter every day. And that’s where author Jana Riess takes the word of God. A popular Mormon blogger at Religion News Service and author of “Flunking Sainthood,” Riess spent four years tweeting every book of the Old and New Testaments with pith and wit.

Now, the complete collection — each chapter condensed to 140 characters — is on sale as “The Twible,” (rhymes with Bible) with added cartoons and zippy summaries for each biblical book.

Her tweets mix theology with pop-culture inside jokes on sources as varied as ”Pride and Prejudice,” “The Lord of the Rings,” and digital acronyms such as LYAS (love you as a sister). To save on precious character count, God is simply “G.”

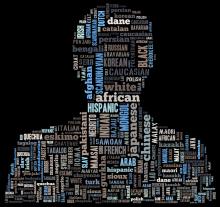

Racism continues to plague our nation. From disparities in the criminal justice system to attacks on voting rights, many of us have sat by as our brothers and sisters are treated unequally. It doesn’t have to be this way.

As “Peace Pastor” Marty Troyer describes in “Subverting the Myth” (Sojourners, December 2013), with a lot of hard work and honest dialogue, racial reconciliation is possible.

People of faith are leading the new movement for racial justice. To become an agent of reconciliation, sign the One Church, One Body pledge and check out the resources below.

ARTICLES

- By Accident of Birth, by Jim Wallis

- Can We Talk? White Privilege Today, by Andrea Ayvazian and Beverly Daniel Tatum

- In the Middle: The Challenge of Racial Reconciliation, by Catherine Meeks

- Ooh! Is That Racism on Your Shoe?, by Chris Rice

- Racism: America’s Original Sin, by Jim Wallis

- To Move Beyond Denial, by Yvonne V. Delk

- Whose America is It?, by Anthony A. Parker

THE DAYS shorten and the scriptures get wild and woolly and Advent begins. Meanwhile, the secular holiday season builds in a frenzy of car commercials (does anyone really get a car for Christmas?), sale flyers, and often-forced cheer. Here are a few books—memoirs, spiritual writings, and art—that can be interesting, grounding, and inspiring companions for a complicated time of year. (They also are much easier to wrap than a car.)

Life stories

Good God, Lousy World, and Me: The Improbable Journey of a Human Rights Activist from Unbelief to Faith, by Holly Burkhalter. Convergent Books. Decades in political and human rights work convinced Holly Burkhalter that there couldn’t be a loving God—until she became a believer at age 52.

Hear Me, See Me: Incarcerated Women Write, edited by Marybeth Christie Redmond and Sarah W. Bartlett. Orbis. I was in prison, and you listened to my story. Moving works from inside a Vermont prison.

God on the Rocks: Distilling Religion, Savoring Faith, by Phil Madeira. Jericho Books. Nashville songwriter, producer, and musician Phil Madeira offers lyrical, wry observations on faith and life, from his evangelical roots to musing on a God who “knows she’s a mystery.”

I CAN’T WRITE a completely unbiased, academic review of this book: Nora Gallagher is a friend, and I know the medical world that she must still navigate, and how wonderful it is when you arrive at the Mayo Clinic. This book is for anyone who plans to die one day and wants to live daily with purpose and with a real God. Those who are or have been physically ill will find a kindred soul in Gallagher, while the healthy will wonder how they will handle the sad, sympathetic gazes from others in the pew when their names are placed on the prayer list.

When she is 60, the vision in one of Gallagher’s eyes begins to fail. She limits the use of her one good eye for fear of losing sight in it too. Not so bad, you might think—except that as a writer, seeing is key to paying for the medical tests and travel she will endure for two years.

Of course all good patients become writers in a way. At first you take random notes in scattered notepads. Finally you redefine yourself as a full-time patient whose life demands documentation of every symptom and test in a little black book that becomes your constant companion. You have now entered what Gallagher calls Oz, the land of illness.

For Gallagher, Oz is strange. Oz is blurry. She is lonely. She is a patient not a person. Oz has many disrespectful, condescending doctors working in machine-like hospital systems that allow 10 minutes for a consult; they must get to the next patient, not solve the mystery of her now-painful, debilitating state.

JAMES DOBSON and Kurt Bruner get three things right in their recent novels Fatherless and Childless: Euthanasia is wrong, married couples should make time to have hot sex, and stay-at-home moms should get some respect.

Pretty much everything else in the novels, the first two-thirds of a trilogy (book three, Godless, is due out in May 2014), is way off and internally incoherent. The plot starts in 2042, when an aging population and economic malaise have motivated the government to legalize euthanasia. Businessman Kevin Tolbert, recently elected to Congress, lectures his peers about the need to stop euthanasia and encourage parenthood in order to revive the economy. His wife Angie’s high school friend Julia Davidson, an allegedly progressive and feminist reporter, is assigned to write a story about him (lecture alert). Meanwhile Kevin and Angie struggle (with mercifully few lectures) with their third child’s diagnosis of Down syndrome. Subplots deal with a disabled teen and an elderly dementia victim who turn (or are pushed) to euthanasia.

Actual euthanasia, as disability-rights groups such as Not Dead Yet have documented, often turns on society defining “dignity” according to physical ability and health instead of the innate value of a human being. These novels, however, ask us to believe the main impetus for euthanasia would come from the drive to reduce the federal deficit, to deal with “swelling entitlement spending.”

What spending? The novels’ elderly and disabled characters are drawn or pushed toward euthanasia because of family financial troubles: There is no mention of any Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid help going to any of them.

IN THE FOREWORD to Where Justice and Mercy Meet: Catholic Opposition to the Death Penalty, Sister Helen Prejean writes, “Welcome to the pages of this amazing book.” Her hospitable remark is not an exaggeration. I have written articles, taught classes, and spoken to church groups about capital punishment; in my judgment this book is the most accessible resource now available for engaging, informing, and perhaps even transforming how readers view the death penalty.

Where Justice and Mercy Meet was edited by death penalty activist Vicki Schieber, philosopher Trudy D. Conway, and theologian David Matzko McCarthy. The book is the product of two years of interdisciplinary courses, discussions, projects, and research—in sociology, political science, philosophy, economics, theater, ethics, and theology—at Mount Saint Mary’s University in Emmitsburg, Md. While the book has a Catholic focus, it should be useful to Christians of all stripes and others interested in addressing this issue.

The volume is divided into four parts. Through skillful section and chapter introductions and segues, the editors have done a fine job of creating an integrated whole. Relevant questions for discussion and action tips make the book perfect for study groups in churches and for the university classroom.

Part I, “The Death Penalty Today,” exposes the realities of the dominant current method of execution (lethal injection), surveys the history of the death penalty debate in the U.S., and suggests the significance of reading or hearing the stories of those affected by murder and capital punishment. Kurt Blaugher’s chapter, “Stirring Hearts and Minds,” meditates on the role of drama in allowing these stories to capture and broaden our imagination, to stimulate reflection, and to compel us to take action for social change. Indeed, stories—from real life as well as from film and literature—surface throughout the volume, with the most moving and memorable ones being the experiences and voices of those whose loved ones were murdered.

Still Shining

David Hilfiker is a retired inner-city physician and writer on poverty and politics who has Alzheimer’s. He writes about his experience, with the hope of helping “dispel some of the fear and embarrassment” that surrounds this disease, on his blog “Watching the Lights Go Out.” www.davidhilfiker.blogspot.com

Transported

Laura Mvula is a British, classically trained musician, songwriter, and former choir director whose debut album,Sing to the Moon,is a lush fusion of soul, jazz, gospel, and pop. While not overtly “about” faith, her arrangements are imbued with spiritual longing and visions of beauty. Columbia

OUR BODIES AND the land are one. Move the earth with your body, dance on it, farm in it, play with it; our final return to it is sacred. The soil is made of clay, like you and me—hydrocarbon molecules, layers of geological and muscular formations, alive. The soil, mountains, and valleys are layered with time like our layered muscle tissue. We dance on the earth in the face of death, for the healing of ourselves and the healing of the land, connected as farmers, dancers, painters, musicians, and lovers of the goodness of the good green earth moving through lament. Our bodies and the earth are one and their healing and grieving are interconnected.

January 2011, around the corner from my house, Anjaneah Williams was murdered, across the street from Sacred Heart Church, pierced in the side, at 2 p.m., walking out from a sandwich shop. It was a Thursday. She died six hours later at Cooper Hospital in the arms of her mother, before the children who deeply loved her. One of the gunman’s stray bullets shot across the street through the stained glass at Sacred Heart. Anjaneah’s death reverberated in the air, an exploding, echoing canyon; a screaming mother in a vacuum, unheard and deafening. Her murder was one of 40 in the neighborhood in the near half-century since the shipyard closed. Forty people on the sidewalks, on the lots where houses once stood, in a neighborhood with 28 known environmentally contaminated sites.

Experienced as the Butlers were in suffering and loss, they were not prepared for the technologically enhanced torments of old age.

Knocking on Heaven's Door tells what can happen when a person's mind and body endure a series of shocks that would naturally lead to decline and death — except that, through various technological interventions, the body is not allowed to decline along with the mind.

In Professor Butler's case, a major stroke wiped out most of his ability to function independently and set him on the road to dementia. At the same time, his heart was slowing down. A year after his stroke, over the opposition of his primary care physician, Butler was fitted with a pacemaker. His cardiologist strongly recommended it. He needed hernia surgery, the doctor said, and his heart was not likely strong enough to survive the operation. So he had the pacemaker installed, he had the surgery, and he was rewarded with another six years of increasingly hellish existence — not only for himself, but also for his wife and his daughter. His mind was shot. His body would not do what he wanted it to do. But his artificially assisted heart kept relentlessly ticking away.

Author Malcolm Gladwell may not be known for writing on religion. His New York Times best-selling books “The Tipping Point,” “Outliers,” “Blink” and “What the Dog Saw” deal with the unexpected twists in social science research. But his newest book, “David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants,” also includes underlying faith-related themes, and not just in the title.

Gladwell said that while researching the book, he began rediscovering his own faith after having drifted away. Here, he speaks with RNS about his Mennonite family, how Jesus perfectly illustrates the point in his new book and how Gladwell’s return to faith changed the way he wrote the book.

The books of Tom Clancy, who passed away this week, contain some of the most detailed description of military weaponry and procedures the public is likely to see. And people want to believe it: Clancy’s world is one in which technology can provide security and the so-called experts can be trusted to protect us. He takes a complex world and doesn’t merely simplify it, but rather creates super humans and super machines that can manage the world’s complexities.

THIS SHORT VOLUME by Jacqueline Battalora, a professor of criminal justice at St. Xavier University in Chicago, addresses a very important topic in American history and society: The legal, social, and political invention of the category of “white people” as a privileged group, which defines them as the normative Americans over against others, variously defined as “black,” “colored,” “Indians,” and “mulatto.”

When English settlers founded the New England colonies, they referred to themselves as British. As more people from other countries of Western Europe arrived in the area, they tended to group those they saw as similar to themselves as Christians, Germans, etc.—the term “white” was not used—over against “Negroes,” Indians, and rival colonizers such as the Spanish and French.

The term white was first used in colonial law after Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, during which some African and European indentured servants formed an alliance. Virginia’s colonial leaders responded with a package of laws that created a racial caste of African-descended slaves, distinguished from European servants. These laws decreed that African slaves could not be freed and free Africans could not hold office, serve in the army, or hold European bond laborers. This group was thus disprivileged, in contrast with those of European descent who were defined as “white.”

Cleats and Dignity

The civil rights struggle for African Americans happened in every sphere of life. Breaking the Line: The Season in Black College Football That Transformed the Sport and Changed the Course of Civil Rights, by Samuel G. Freedman, tells of two great black coaches in the tense year of 1967. Simon & Schuster

Catching Fire

One project of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture is the Pentecostal and Charismatic Research Initiative, which funded research in more than 20 countries. PCRI resources include the informative recent report, “Moved by the Spirit: Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity in the Global South.” crcc.usc.edu/pcri

We live in a church context where so many embrace unbiblical either/or understandings of Christianity: Either evangelism or social action, either inward journey or outward journey. And on and on.

It is the widespread onesidedness that makes Rich Nathan’s new book so exciting.

Every so often a fiction book makes a splash in the swamp of Christian literature, which is predominately ruled by non-fiction reads. The Shack by Wm. Paul Young would be one modern example and, reaching back just a bit more, In His Steps by Charles M. Sheldon would be another.

It's happened again.

Frank Schaeffer's And God Said, “Billy!” is a work of Christian fiction that just barely fits into the “Christian” sub-category of fiction. That's not to say it doesn't come with a heavy dose of Christian characters and culture (it does) as much as it is to say, unlike the other must-read fictions of the past that I just mentioned, this book could and should have a much broader appeal. So much so, I almost titled this review, “The Book Everyone Needs to Read ...”.

One of my favorite stories is about the interview I wanted most, but didn’t get.

It was 2005 and I had just signed a contract to write what would be my first book — a collection of profiles of mostly well-known people about their spiritual lives. Artists. Writers. Thinkers. Scientists. The odd rock star.

Sitting in my publisher’s office, she asked me to dream out loud: If I could interview anyone for the project, who was No. 1 on my wish list?

I answered without hesitation: Seamus Heaney.

Reza Aslan begins of his book, Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, with a prescient warning: “Scholars tend to see the Jesus they want to see. Too often they see themselves—their own reflection—in the image of Jesus they have constructed” (xxxi).

I don’t think Aslan had himself in mind when wrote that statement, but you should be warned: the Jesus in Zealot is Aslan’s own false construction.

His central thesis is that the Jesus of history, and the God Jesus believed in, demanded violence in the face of political and religious oppression. Here’s one of the relevant passages:

[F]or those seeking the simple Jewish peasant and charismatic preacher who lived in Palestine two thousand years ago, there is nothing more important than this one undeniable truth: the same God whom the Bible calls a “man of war”(Exodus 15:3), the God who repeatedly command the wholesale slaughter of every foreign man, woman, and child who occupies the land of the Jews, the “blood spattered God” of Abraham, and Moses, and Jacob, and Joshua (Isaiah 63:3) the God who “shatters the heads of his enemies,” bids his warriors to bathe their feet in their blood and leave their corpses to be eaten by dogs (Psalm 68:21-23)—that is the only God that Jesus knew and the sole God that he worshipped. (122, emphasis in the original.)

The problem that I have with this passage is indicative of the problem that I have with the way Aslan constructs his Jesus. He constantly picks and chooses which verses from the Bible he uses to support his claim that Jesus was a warrior messiah whose goal was to violently overthrow the Roman and religious establishment. He peels away all passages that conflict with his construction so that he can show us what Jesus was truly like.

Well, what Aslan thinks Jesus was truly like.