Afghanistan

Kabul—“I woke up with the blast of another bomb explosion this morning,” Imadullah told me. “I wonder how many people were killed.” Imadullah, an 18-year-old Afghan Peace Volunteer from Badakhshan, had joined me at the APVs’ Borderfree Community Centre of Nonviolence.

The news reported that at least three Afghan National Army soldiers were killed in the suicide bomb attack, in the area of Darulaman. Coincidentally, the Afghan Peace Volunteers had planned to be at the Darulaman Palace that same morning. To commemorate Gandhi’s birthday and the International Day of Nonviolence, we wanted to form a human circle of peace at the palace, which is a war ruin. But the police, citing general security concerns, denied us permission.

Imadullah and Rauff, another APV member, continued discussing the attack. Rauff believes that the latest string of suicide bombings in Kabul have been in response to actions of the newly formed government. The Taliban condemned the new government — led by former World Bank official Ashraf Ghani and ex-warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum — for signing the new U.S. /Afghanistan Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA).

Listening to Imadullah’s and Rauff’s concerns over the latest string of attacks, I wondered if I myself had become inured to this sober Afghan reality of perpetual war.

Here in Kabul, one of my finest friends is Zekerullah, who has gone back to school in the eighth grade although he is an 18-year old young man who has already had to learn far too many of life’s harsh lessons.

Years ago and miles from here, when he was a child in the province of Bamiyan, and before he ran away from school, Zekerullah led a double life, earning income for his family each night as a construction crew laborer, and then attempting to attend school in the daytime. In between these tasks, the need to provide his family with fuel would sometimes drive him on six-hour treks up the mountainside, leading a donkey on which to load bags of scrub brush and twigs for the trip back down. His greatest childhood fear was of that donkey taking one disastrous wrong step with its load on the difficult mountainside.

And then, after reaching home weary and sleep deprived and with no chance of doing homework, he would, at times, go to school without having done his homework, knowing that he would certainly be beaten. When he was in seventh grade, his teacher punished him by adding 10 more blows each day he came to school without his homework, so that eventually he was hit 60 times in one day. Dreading the next day when the number would rise to 70, he ran away from that school and never returned.

Now Zekerullah is enrolled in another school, this time in Kabul, where teachers still beat the students. But Zekerullah can now claim to have learned much more, in some cases, than his teachers.

During a recent visit to Kabul’s Emergency Surgical Center for Victims of War, the staff shared with us their sense of what's happening around the country, derived from the reports of staff working at several dozen clinics and at their main hospitals in two other provinces. They described Kabul as "a bubble." They told us full-scale wars are being fought between quite heavily armed forces in both eastern and southern Afghanistan, although the news coverage that goes beyond Afghanistan generally pertains to Kabul. The groups fighting the Afghan government include various warlords, the Taliban, drug kingpins, and foreign fighters, some of whom may be strategizing ways to cut off the roads to Kabul. The Kabul “bubble” can be quite vulnerable.

The borders now vanishing in the Middle East – the most radical transformations of the map here since the post-WWI Sykes Picot agreement – are being redrawn in chaos and fear. The bubbles that burst here are the hopes for peace in a world avid for control of this region and its resources. Unfortunately, durable structures of separation and domination make it difficult for many young Afghans to fulfill their longings to connect meaningfully, peacefully, and stably with a saner world united under one blue sky.

Bio: Kelly and Peter Shenk Koontz spent the last three years serving in Kabul, Afghanistan, through a Mennonite Central Committee partner.

Website: MCC.org

1. What work were you doing in Afghanistan?

We worked with a Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) partner in Kabul as Peacebuilding Project Managers. Our job was to integrate peacebuilding within different sectors of the partner organization, including adult education, community development, and many others. Day-to-day, this primarily meant developing curriculum and planning and conducting trainings for a variety of contexts—including rural community development teams and university students in Kabul.

Last week, here in Kabul, the Afghan Peace Volunteers welcomed activist Carmen Trotta, from New York, who has lived in close community with impoverished people in his city for the past 25 years, serving meals, sharing housing, and offering hospitality to the best of his ability. Put simply and in its own words, his community, founded by Dorothy Day, exists to practice “the works of mercy” and to “end the works of war.” We wanted to hear Carmen’s first impressions of traveling the streets of Kabul on his way from the airport to the working class neighborhood where he’ll be staying as the APVs’ welcome guest.

He said it was the first time he’d seen the streets of any city so crowded with people who have no work.

Carmen had noticed men sitting in wheelbarrows, on curb sides, and along sidewalks, unemployed, some of them waiting for a day labor opportunity that might or might not come. Dr. Hakim, the APV’s mentor, quoted Carmen the relevant statistics: the CIA World Fact Book uses research from 2008 to put Afghanistan’s unemployment rate at 35 percent — just under the figure of 36 percent of Afghans living beneath the poverty level. That’s the CIA’s unemployment figure. Catherine James, writing in The Asian Review this past March, noted that “the Afghan Chamber of Commerce puts it at 40%, the World Bank measures it at 56% and Afghanistan’s labor leaders put it at a shocking 86%.”

“The final perversion is the reversal of who is the real victim here: the commander of a military base whose drones kill innocent people halfway around the world, or those innocent people themselves who are the real ones in need of protection from the terror of U.S. drone attacks?”

During my recent visit to Gangjeong, on Jeju Island, South Korea, where a protest community has struggled for years to block construction of a U.S. military base, conversations over delicious meals in the community kitchen were a delightful daily event. At lunchtime on my first day there I met Emily and Dongwon, a young and recently married couple, both protesters, who had met each other in Gangjeong. Emily recalled that when her parents finally travelled from Taiwan to meet her partner, they had to visit him in prison.

Dongwon, who is from a rural area of South Korea, had visited Gangjeong and gotten to know the small protest community living on the Gureombi Rock. Drawn by their tenacity and commitment, he had decided to join them. When a barge crane was dredging the sea in front of Gureombi Rock, Dongwon had climbed up to its tip and declined to come down. On February 18, 2013, a judge sentenced him to one year in prison for the nonviolent action.

The newly freed soldier who spent nearly five years in captivity in Afghanistan has the mental and physical toughness to survive the experience, his former pastor said.

“If there’s anybody I can think of pulling through this, and doing well, it’s Bowe,” said Philip Proctor, who was pastor of Sovereign Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Boise, Idaho, when Bergdahl was a teenager.

“He has the mental and physical stamina not to be crushed by this experience,” Proctor said.

An Afghan security guard allegedly shot and killed three Americans at a hospital in Kabul on Thursday. The three killed were doctors, including a visiting father and son.

Another doctor and a U.S. nurse were wounded in the attack.

District Police Chief Hafiz Khan said a guard suddenly turned his weapon on the staff he was supposed to be protecting at Cure International Hospital and started shooting.

“Five doctors had entered the compound of the hospital and were walking toward the building when the guard opened fire on them,” said Kanishka Bektash Torkystani, a spokesman for the Ministry of Health. “Three foreign doctors were killed.”

On March 28 at about 4 p.m., the Afghan Peace Volunteers heard a loud explosion nearby. For the rest of the evening and night, they anxiously waited for the sound of rocket fire and firing to stop. It was reported that a 10-year-old girl, and the four assailants, were killed.

Four days later, they circulated a video, poem and photos prefaced by this note:

“We had been thinking about an appropriate response to the violence perpetrated by the Taliban, other militia, the Afghan government, and the U.S./NATO coalition of 50 countries.

So, on the 31st of March 2014, in building alternatives and saying ‘no’ to all violence and all forms of war-making, a few of us went to an area near the place which was attacked, and there, we planted some trees. -- Love and thanks, The Afghan Peace Volunteers"

WHEN CHIEF MASTER Sergeant Harry Marsters returned in 2008 from his time in Iraq, he knew something wasn’t right. At 54, the 32-year veteran of the Air Force—with 27 years full time in the military and the remainder as a reservist with the Air National Guard—felt that as one of the “older folks” he knew what to expect upon return from his assignment with the communications squad at the Kirkuk Regional Air Base in northern Iraq.

Marsters’ squadron trained Iraqi forces in the operation and maintenance of aerial surveillance equipment on the base, which housed 1,000 Air Force and 2,500 Army troops. As first sergeant he acted as a liaison to the Air Force troops and ensured the well-being of those stationed there. It was a job he relished, pouring care into building connections with the airmen and women, spending time with the chaplains, and coordinating recreation and morale-building activities.

Though Air Force personnel never left the base, they were subjected to the ever-present threat of randomly timed mortar rounds launched by insurgents. They also took part in nighttime “patriot details” in which Air Force personnel and soldiers lined the base’s runway as the bodies of fallen soldiers were loaded onto planes for transport back to the United States. But Marsters says he was most upset by what he felt was harsh treatment of the Iraqi nationals who came to work on the base.

“They were treated like criminals,” he says of the extensive searches and intimidation Iraqis received when going through base security. “Everyone in Iraq is not evil, bad, and nasty. It’s a very small group of people who are raising hell and trying to hurt the country. The average person is just trying to make some money and take care of his or her family.”

Two weeks ago in a room in Kabul, Afghanistan, I joined several dozen people — working seamstresses, some college students, socially engaged teenagers, and a few visiting internationals like myself — to discuss world hunger. Our emphasis was not exclusively their own country’s worsening hunger problems. Rather, tmhe Afghan Peace Volunteers, in whose home we were meeting, draw strength from looking beyond their own very real struggles.

With us was Hakim, a medical doctor who spent six years working as a public health specialist in the central highlands of Afghanistan and, prior to that, among refugees in Quetta, Pakistan. He helped us understand conditions that lead to food shortages and taught us about diseases, such as kwashiorkor and marasmus, which are caused by insufficient protein or general malnutrition.

We looked at U.N. figures about hunger in Afghanistan, which show malnutrition rates rising by 50 percent or more compared with 2012. The malnutrition ward at Helmand Province’s Bost Hospital has been admitting 200 children a month for severe, acute malnutrition — four times more than in January 2012.

A recent New York Times article about the worsening hunger crisis described an encounter with a mother and child in an Afghan hospital: “In another bed is Fatima, less than a year old, who is so severely malnourished that her heart is failing, and the doctors expect that she will soon die unless her father is able to find money to take her to Kabul for surgery. The girl’s face bears a perpetual look of utter terror, and she rarely stops crying.”

Photos of Fatima and other children in the ward accompanied the article. In our room in Kabul, Hakim projected the photos on the wall. They were painful to see and so were the nods of comprehension from Afghans all too familiar with the agonies of poverty in a time of war.

Week after bloody week, the chart of killings lengthens. And in Afghanistan, while war rages, a million children are estimated to suffer from acute malnourishment as the country faces a worsening hunger crisis.

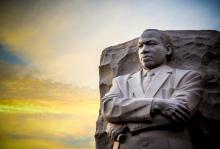

Around this Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, we can and should remember the dream Dr. King announced before the Lincoln Memorial, the dream he did so much to accomplish, remembering his call (as the King Center asks) for nonviolent solutions to desperate concerns of discrimination and inequality within the U.S. But we shouldn't let ourselves forget the full extent of Dr. King's vision, the urgent tasks he urgently set us to fulfill on his behalf, so many of them left unfinished nearly 46 years after he was taken from us.

The fire in the Chaman e Babrak camp in Kabul, Afghanistan, began in Nadiai’s home shortly after noon. She had rushed her son, who had a severe chest infection, to the hospital. She did not know that a gas bottle was leaking; when the gas reached a wood-burning stove, flames engulfed her mud hut and extended to adjacent homes, swiftly rendering nine extended families homeless and destitute in the midst of already astounding poverty. By the time seven fire trucks had arrived in response to the fire at the refugee camp, the houses had burned to the ground.

No one was killed. When I visited the camp, three days after the disaster, that was a common refrain of relief. Nadiai’s home was on the edge of the camp, close to the entrance road. Had the fire broken out in the middle of the camp, or at night when the homes were filled with sleeping people, the disaster could have been far worse.

Even so, Zakia, age 54, who also lives in the camp, said this is the worst catastrophe she has seen in her life, and already their situation was desperate.

Kabul, Afghanistan, is “home” to hundreds of thousands of children who have no home. Many of them live in squalid refugee camps with families that have been displaced by violence and war. Bereft of any income in a city already burdened by high rates of unemployment, families struggle to survive without adequate shelter, clothing, food, or fuel. Winter is especially hard for refugee families. Survival sometimes means sending their children to work on the streets, as vendors, where they often become vulnerable to well-organized gangs that lure them into drug and other criminal rings.

Last year, the Afghan Peace Volunteers (APV), young Afghans who host me and other internationals when we visit Kabul, began a program to help street children enroll in schools. The volunteers befriend small groups of children, get to know the children’s families and circumstances, and then reach agreements with the families that if the children are allowed to attend school and reduce their working hours on the streets, the APVs will compensate the families, supplying them with oil and rice. Next, the APVs buy warm clothes for each child and invite them to attend regular classes at the APV home to learn the alphabet and math.

Yesterday, Abdulhai and Hakim met a young boy, Safar, age 13, who was working as a boot polisher on a street near the APV home. Abdulhai asked to shake Safar’s hand, but the child refused. Understandably, Safar may have feared Abdulhai. But when Abdulhai and Hakim told Safar there were foreigners at the APV office who were keen to help, he followed them into our yard.

AS THE U.S. prepares to officially (but not completely) pull out its military from Afghanistan by the end of 2014, some wonder whether it all was a waste. More than a decade of war has cost tens of thousands of lives and hundreds of billions of dollars. But the balance sheet of “lessons learned” shows some less-depressing calculations.

In the last several years, U.S. generals have repeatedly told Congress and the U.S. public that “there is no military solution” to the war in Afghanistan. This marks a significant shift in military thinking. In the early 2000s, the boastful, overconfident views that wars in Afghanistan and Iraq would be quick and easy outnumbered more cautious and skeptical military voices. If nothing else, more military leaders today are forthrightly speaking out against the fantasy of firepower solutions to complex political problems.

The U.S. and its Western allies are also learning a related lesson: The lack of legitimate governance is a fundamental cause of much of the world’s violence. Afghanistan’s political leaders who opposed the Taliban became de facto Western allies, even though many had ruled by force and racked up their own long list of human rights abuses. In the rush to set up a new government to replace the Taliban, the West propped up corrupt and tyrannical warlords as provincial governors, dooming hopes for an Afghan democracy and authentic leaders with popular support.

Counterinsurgency projects attempted to pull support from the Taliban and other insurgents by winning Afghan hearts and minds so they would trust their government. But Western military forces learned that free handouts of Western aid money could not fundamentally change the corrupt nature of the Afghan government or its public image.

As Ramzi Kysia writes in "The Song Remains" (Sojourners, August 2013), after decades of work, Kathy Kelly’s commitment to peace and nonviolence remains strong. When Sojourners editorial assistant, Dawn Araujo, caught up with her in June, Kelly was between visits to Afghanistan and her work with the Afghan Peace Volunteers. She was spending her “down” time protesting drones, nuclear weapons, and organizing a U.S.

The United Nations issued a report on Wednesday stating that the number of civilians killed or wounded in Afghanistan rose by 23 percent in the first six months of 2013, with women and children faring the worst — killed by roadside bombs almost every day. An earlier UN report noted that

"Afghanistan remains one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a child."

Over a third of Afghans are living in abject poverty, violence is escalating as NATO forces withdraw, and years of international aid has done little to decrease the abuse of women and children.

Click here to see the Atlantic's photos series on Afghan children.

A military judge ruled Tuesday that Pfc. Bradley Manning was not guilty of aiding the enemy. In 2010, he was arrested for allegedly passing classified materials to the website WikiLeaks. If Manning had been found guilty of aiding the enemy, he could have been sentenced to life in prison. The sentencing phase of the trial will begin Wednesday.

The New York Times reports:

Private Manning had already confessed to being WikiLeaks’ source for a huge cache of government documents, which included videos of airstrikes in which civilians were killed, hundreds of thousands of front-line incident reports from the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, dossiers on men being held without trial at the Guantánamo Bay prison, and about 250,000 diplomatic cables.

But while Private Manning had pleaded guilty to a lesser version of the charges he was facing, which could expose him to up to 20 years in prison, the government decided to press forward with a trial on a more serious version of the charges, including “aiding the enemy” and violations of the Espionage Act, which could result in a life sentence.