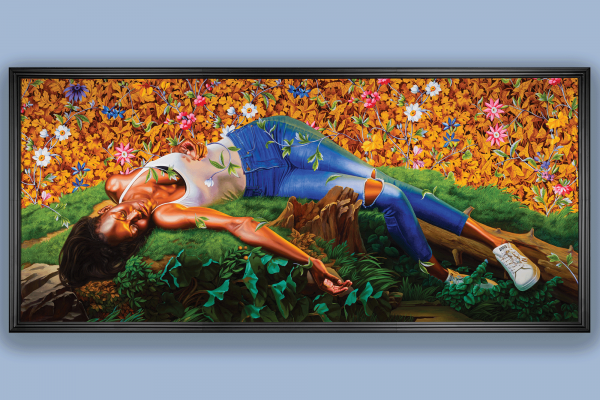

DID THE TRAVELER who saw me asleep on the floor of an airport prayer room think I was dead? I wore black leggings, a black hooded dress, and black socks. My black shoes were tucked neatly beside me. My puffy black jacket served as a pillow atop my black backpack. My scarf was a blanket over my face. Perhaps I looked like a shrouded portrait of death. But I was and am very alive, just tired. After a red-eye flight with a long layover, I came seeking rest.

I sought the hidden upper room, described on the airport’s website as “a calm respite before and after flights,” to restore my soul on a Sunday morning. After sitting, then kneeling, I finally curled up in a fetal position and drifted off to sleep until an employee entered the immaculate space. The keys on her hips jangled as she wiped and rearranged the holy books and beads on the altar. As she refolded prayer mats, I silently prayed for her. The jangling got closer as she announced that she needed to vacuum. I asked if I could remain in the room. She told me the room was not for napping and that a person had opened the door earlier, saw me, thought I was dead, and walked out. Dear traveler, dear prayer-room cleaner, if you are reading this, if you thought I might have been dead, why didn’t you first say, “Are you OK?”

Read the Full Article