EVER SINCE I was little, my imagination has been shaped by superhero worlds, lore, and comic and animated adaptations. And while more “realistic” adaptations are the trend on the big screen, what enthralled me about characters such as Batman wasn’t that I thought he could be real; I was tuned instead to the ethos behind the caped crusader.

Superhero stories often seem limitless. At their best, they stretch the imagination to ask what type of world we want to exist and what it would take to get us there, while acknowledging hardships along the way.

Recently, I began a rewatch of the DC Animated Universe: TV shows, feature films, and shorts that aired mainly from 1992 to 2006. These shows were the first to capture my attention and shape my imagination. Batman: The Animated Series was my first love, with Kevin Conroy’s Batman and Mark Hamill’s Joker seared into my consciousness. As I watched, I made a particular note about the moral imagination of these shows: Superheroes in these shows don’t just refuse to kill — a theme recurring across superhero worlds — they refuse to even let anyone die.

Take Season 1, Episode 11 (S1 E11) of Superman: The Animated Series: Lex Luthor’s weapons factory is about to explode, with spilled molten metal splashing about. Lana Lang is hanging by a thread above certain death; so is Lex Luthor, who unintentionally caused this mess in his attempt to kill Superman. But then, at the last moment, Superman bursts forth from under the molten waves, crashing out of the top of the factory just before it explodes, with Lana in one arm and the villain in the other.

It’s a scene that strains credulity. There’s an improbability of timing, a lack of “logic” in doubling back for the person trying to kill you, and the storyteller’s refusal to explain how Superman managed to save the villain. But what’s key here is the insistence, and flaunting, that Superman would save the villain. It doesn’t need an explanation; it’s assumed.

For a while, I was paying attention to how the writers made this subtext believable. Superman saves some villains in hopes they can be rehabilitated, others because they are being used by larger, more villainous characters. Why? The simple answer is that these were shows for families and children. The same reason the comic book’s “League of Assassins” became the TV show’s “Society of Shadows” and villains set out to “destroy” rather than “kill” heroes.

But this death-resisting subtext becomes dialogue in S2 E9 of Superman: The Animated Series when some kids plead with Metallo, a villain disguised as a hero, to save Lois Lane from an exploding volcano. “Superman wouldn’t let anyone die, no matter how bad they were,” the kids protest. “I’m not Superman,” Metallo retorts.

Apocalyptic nonviolence and the comics

THE RELATIONSHIP TO death in these shows isn’t denial of the reality of death; after all, Superman begins with the death of the planet Krypton and all its inhabitants, save our Man of Steel who is rocketed to Earth. Rather, death is treated as something to resist. Death comes for us all, but so far as it depends on our heroes, it won’t come today.

In this logic, I see the Christian nonviolence that Myles Werntz and David Cramer call “apocalyptic nonviolence”: the stream of the Catonsville Nine, William Stringfellow, and René Girard.

“Apocalyptic nonviolence takes as its starting point ... that Jesus’ death and resurrection call for Christians to actively oppose the machinations of Death in the world,” the two write in A Field Guide to Christian Nonviolence. “[What] is primary to apocalyptic nonviolence is the guiding conviction that nonviolence continues the work of God in Christ, which exposes Death for what it is. As such, apocalyptic nonviolence is more confrontational in nature, in keeping with what is at stake: the contest between the resurrection life of Jesus and the power of Death.”

This is a nonviolence that is willing to disregard the conventional wisdom that peace comes from the annihilation of enemies. Insomuch as our heroes represent the good in a story, they can be seen to represent Christ’s defeat of death. Central to being a hero is the assumption that you save every life you can. Following, however, is a second assumption key to these shows: The Big Blue Boy Scout will turn our villains over to the other blue — the police and prison system.

These assumptions work in tandem: It’s not Superman’s job to be judge, jury, and executioner, but it is someone’s job. In one particularly jarring episode, Superman saves the life of a man wrongfully on death row, only to nonchalantly turn the real killer over to the gas chamber.

I began to wonder why heroes were powerful enough to resist death but largely incapable of seeing past systems of incarceration. Superman just keeps returning his villains to “Stryker’s Island Penitentiary” in the river of Metropolis (a not-so-subtle nod to Riker’s Island in New York’s East River). Batman seems resigned to the cat-and-mouse game he plays with the Joker, never asking about root causes.

While crooked cops and corrupt systems aren’t foreign to these shows, the logic is that police are failing to live up to their role in society, not that their role is inherently harmful. This mirrors reality, where even the most heinous of police executions lead people to bemoan individual “bad apples,” despite the wealth of evidence that the structure and practice of policing itself is harmful.

For example, the Institute for Justice’s “Policing for Profit” report on civil asset forfeiture found that state and federal authorities took a combined worth of $68.8 billion from people suspected of crimes between 2000 and 2019. In three of the six years between 2014 and 2019, police took more in value than all burglaries in that year.

“We keep us safe”

THANKFULLY, I'M NOT the only one thinking about this. Eve L. Ewing, the sociologist, poet, and writer of Marvel’s Ironheart (2018) addressed abolition in comics on The Ezra Klein Show in 2021. Ironheart, aka Riri Williams, is a 15-year-old Black girl from Chicago, a genius being mentored by the AI ghost of Tony Stark (Iron Man) and wearing a self-made suit of armor similar to his.

“I consider myself an abolitionist, and so many comics that I grew up reading and so many stories end by the hero binding the bad guy up and turning them over — here you are, officer,” Ewing said. “But it’s funny that there aren’t more serious critiques of policing that emerge from the superhero world.”

For Ewing, questioning police presence in comics wasn’t just about her own abolitionist beliefs. “[Riri Williams] almost certainly has seen policing work in her community in ways that are harmful, ... has seen people who she knows to be good be victimized by the police. It just didn’t make sense to me that she would just inherently trust them.”

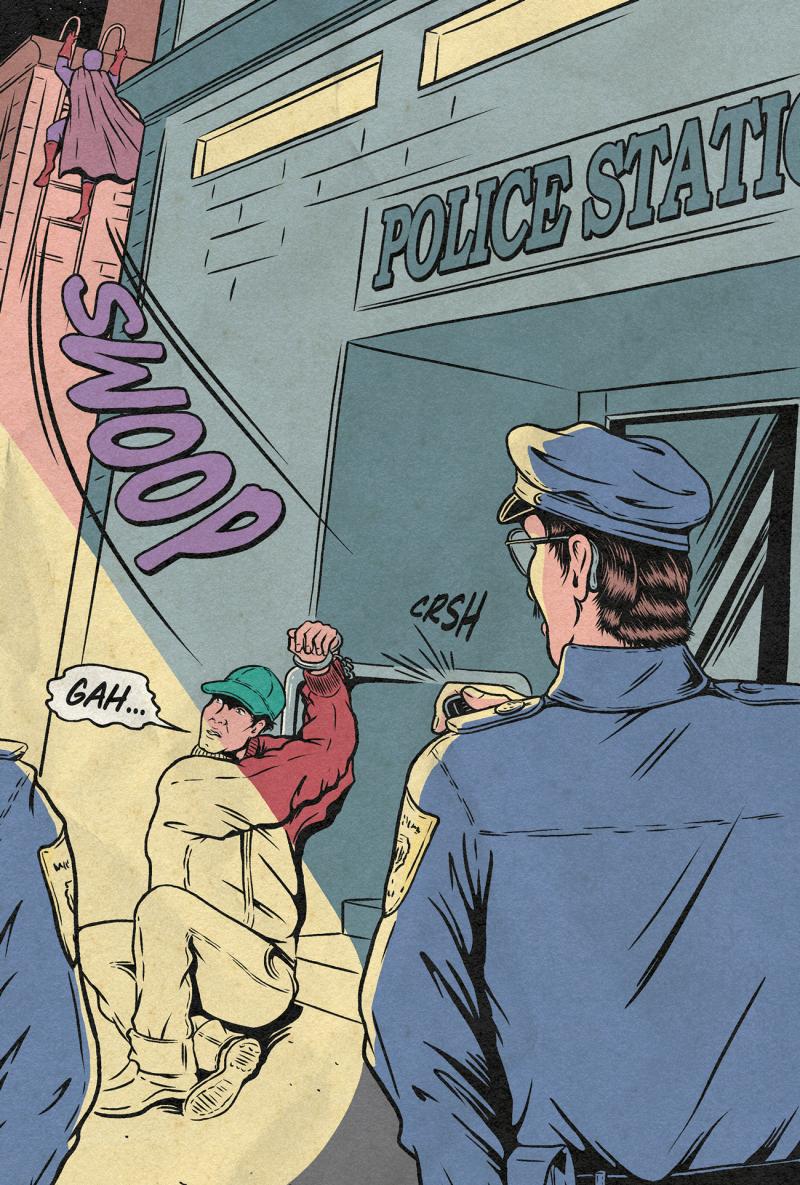

atencio.comics.inline1.jpg

When Williams interacts with the police in Ironheart, she is largely nonchalant. She doesn’t demand they quit their profession or go on a diatribe against policing — but neither does she laud their work nor interact with them beyond necessary. When a friend goes missing, Williams works her own networks and relationships. When the police make their way to the scene of Williams’ battle with a villain, she doesn’t feel the need to stick around and help them with detective work.

Instead, abolition is most visible in Williams’ impulse to turn to her friends, family, and community. She doesn’t kill (though it’s not clear that it’s entirely off the table, it’s just not her first impulse). It’s an exercise in imagining the oft-repeated abolitionist mantra, “We keep us safe.”

Abolitionist impulses don’t need to be reserved for Black heroes. A core motivation for Batman has always been bettering Gotham. The only thing holding him back from trying more radical approaches is the imagination of authors. We don’t need Batman/Bruce Wayne to undergo a Zacchaeus-like transformation and give away his wealth. But we do need a Batman who is trying to get to the root of the problem. It doesn’t take the “world’s greatest detective” to see that the system is designed to oppress and uphold hierarchies.

Crafting a world we can’t live without

THE POTENTIAL FOR these stories is built into the universe that already exists. What if Batman and Superman tracked the effect of overpolicing and incarceration in the lives of Gotham’s and Metropolis’ poorest citizens?

Batman would find that it’s by design, not coincidence, that so many of his villains are incarcerated at Arkham Asylum. A report from the Ruderman Family Foundation, a disability advocacy group rooted in Jewish values, notes that between one-third and one-half of people killed by police are disabled. And a 2017 study in the American Journal of Public Health found that Black disabled people are twice as likely to be arrested as white disabled people.

Superman would find that injustice is rampant within the legal system. About 90 percent of the people incarcerated on Riker’s Island (and perhaps its fictional counterpart) have not been convicted of a crime, according to the Center for Justice Innovation. And the Vera Institute of Justice reported that, as of March 2022, “there were 4,682 people waiting for their trials in New York City jails. Of them, 2,206 had been waiting for six months or more, and 1,474 had been waiting more than a year.” Superman’s desire for justice does not need to be constrained to “stopping crime” — a poor metric for any of us pursuing justice.

These are the types of realities that radical thinkers can explore through comics. Ruha Benjamin, professor of African American studies, says that we must “remember to imagine and craft the worlds you cannot live without, just as you dismantle the ones you cannot live within.” Comics give us a chance to take that maxim to the extreme.

Ironheart writer Ewing isn’t the only one exploring radical politics and comics. Ta-Nehisi Coates has authored Captain America and Black Panther runs, and recently Adam Serwer contributed to a Black Panther collection.

Coates said he sees comics as a chance to form imaginations. “This is rude to say, but there are people that I recognize I can never get to because their imagination is already formed. And when their imagination is formed, no amount of facts can dislodge them,” Coates said on The Ezra Klein Show. In writing superhero stories, Coates is trying to stretch imaginations, redefine what is possible, and use symbols and imagery to draw us back to our material reality. “The symbols actually matter because they communicate something about the imagination, and in the imagination is where all of the policies happen,” he said.

Theologian Walter Brueggemann writes in The Prophetic Imagination that a prophet uses symbols to “express a future that none think imaginable.” It’s the task of prophets to “recognize how singularly words, speech, language, and phrase shape consciousness and define reality.”

With superheroes, it just so happens these symbols are sewn on the chest.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!