IN 1998, I was 24 years old and had just been hired as an assistant to Harvey Weinstein, one of the most powerful men in Hollywood. Within two months, my new boss attempted to rape me in a hotel at the Venice Film Festival.

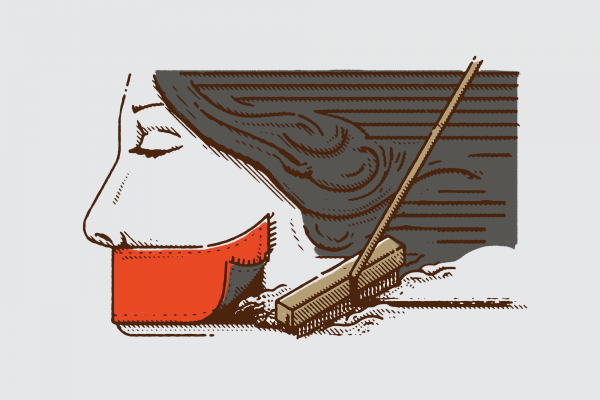

I wanted to report Weinstein to his superiors; instead I was silenced by an egregious and restrictive nondisclosure agreement that prevented me from speaking to family, friends, doctors, lawyers, or therapists about what happened. I was imprisoned in this silence for 20 years.

Two years after The New York Times and The New Yorker broke the Harvey Weinstein story, I broke my nondisclosure agreement. I also published an op-ed in The New York Times: “Harvey Weinstein Told Me He Liked Chinese Girls.”

I was deluged with messages of support from the Asian American community, from the Christian community, and a few from the intersection of the two. One message from a member of my home church stopped me in my tracks: “I’m so sorry you felt unable to share your struggles with us, back in the day. I wish we had been able to pray with you.”

Nondisclosure agreement aside, could I have come to my church for support at the time of the assault?

Read the Full Article