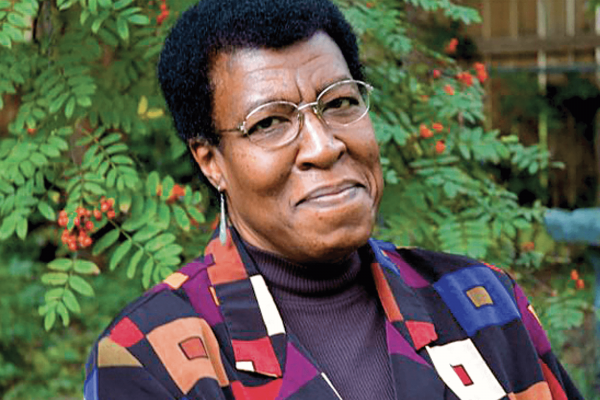

IN MARCH , I made my first, and hopefully last, “panic-buy” of the pandemic: three survivalist books that look more like they belong in a nuclear bunker than on my bookshelves amid the theology, poetry, and knitting patterns. My purchases were, however, inspired by my reading Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, classics by the science fiction literary giant Octavia E. Butler (1947-2006).

In these novels, Lauren Olamina—a young, disabled black girl—survives the apocalypse and helps rebuild society with her knowledge of edible wild plants, her sheer will and bravery, and her newfound religion, Earthseed. Lauren’s ability to adapt, to change, is her route through unimaginable suffering and the bedrock of her faith.

Originally published in 1993 and 1998, respectively, Butler’s Parable books were reissued last year, highlighting their current resonance. Sower introduces us to the United States in 2024, a dystopia ravaged by global warming, capitalism, and violence. Slavery, misogyny—the witch-burning kind—homelessness, and addiction are rampant. Lauren’s community is secure as long as the walls that surround it stand; as she rightly senses, walls are wont to crumble. She launches a backup plan that offers a hard hope within relentless loss. Talents continues Lauren’s, and her daughter Asha’s, journeys over the coming decades as the U.S. faces rising terrorist Christian nationalism and the election of an ultraconservative president who wants to “make America great again.”

Butler’s vision of the future is, as Talents’ back cover says, “shockingly prescient.” However, her gift is not simply the prophetic. Countless scenes evoke historic atrocities—transatlantic slavery, the Holocaust, U.S. Indian boarding schools. Beholding widespread poverty, illiteracy, and disease, Lauren wonders what century life in the 2030s is approximating. The 19th? 18th? As society regresses, Lauren’s journey and religion make clear that we can’t “go back.”

As with COVID-19, the Parable books reveal deeper fissures, preexisting pressures exploding at the foundation.

The strength of Butler’s storytelling is its personal appraisal of this societal cataclysm. Lauren observes, “People ignore one another in self-defense. I find this both useful and frightening.” Relationships—sibling, parent, stranger, neighbor—inhabit the heart of the novels and social collapse.

Butler resisted claims of literary clairvoyance and instead framed her books as cautionary tales. She named Sower and Talents after Matthean parables containing this assessment of human capacity and choice: “Whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” Abundance and lack determine fates.

When I purchased extreme survivalist literature earlier this year, I misread Butler’s lessons, erring (though with less lethal outcomes) like those who panic-bought guns. What we have may well determine our survival, but discerning what to have in abundance is key.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!