JEWISH NEW TESTAMENT scholar Amy-Jill Levine claims that all religions are a little bit supersessionist. Christian supersessionism — which understands God’s covenant with Christians to nullify God’s covenant with the people of Israel — has been so mainstream throughout most of Christian history that it has hardly required articulating. It was just the anti-Jewish water in which we swam. Following the Holocaust, however, Christians recognized how much we’d weaponized supersessionism into antisemitism, which provided support for Nazi and white supremacist ideologies and perpetuated anti-Jewish violence. Unfortunately, Levine argues, no exegetical maneuver can fully expunge supersessionism from the New Testament — though many have tried. It’s there. And the authority of God’s word in Christian lives keeps its dangerous power ever-present.

Still, Paul’s letter to the church in Rome (which we read this month) contains Paul’s own grappling with these questions. Chapters 9 to 11 — wherein Paul corrects some of the Gentile converts who think God has now rejected the covenant with Israel — comprise the hook on which most contemporary attempts to dismantle supersessionism hang their hat. So, we’ll pay special attention to these.

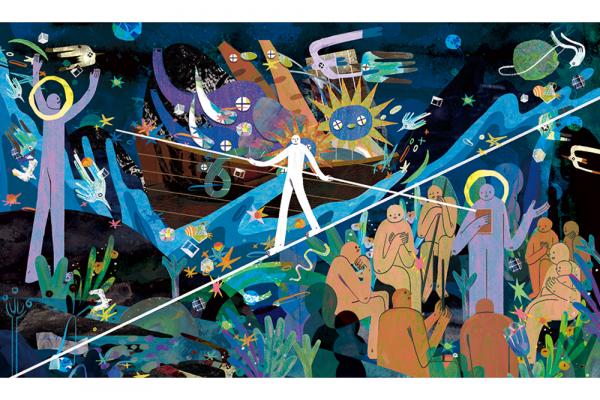

This isn’t going to be an easy fix — particularly for Christians (like me!) who want to hold fast to the gospel, atone for complicity with antisemitism, and stand in solidarity with Palestinians under occupation. Still, I trust God’s promises: I believe both that God’s covenant with Israel endures and that Jesus is the Messiah. So, this month, we are going to sit with the discomfort of failing while attempting the impossible. Because, in trying, we might find a new way through.

August 6

Taking a First Step

Isaiah 55:1-5; Psalm 145:8-9, 14-21; Romans 9:1-5; Matthew 14:13-21

IN THE CHRISTIAN IMAGINATION, theologian Willie James Jennings interprets early church antisemitism as a training camp where we learned how to hate “the other” — a skill Christians then transferred to every “other” we helped construct. For Jennings, this means Christianity is now infected with the original sin of this hatred. To repent of this sin in the full sense — not just regret it but turn back from it — we must recall that Jews are not the other to Christians, but that Christians are the other to Jews. Put differently, the people of Israel are not “saved” by being grafted onto Christianity; rather, the fullness of Christian salvation comes through Christians being grafted into Israel (see Romans 11:17-24).

To repent — first to look back, then look forward anew — requires directing our penitent gaze to where the Old and New Testaments connect. (I’m avoiding the easy non-fix of just changing Old and New terminology here.) In this week’s readings, a penitent gaze wouldn’t interpret the psalmist and Isaiah’s promises that God will feed Israel as merely prefiguring Jesus feeding the 5,000 (Matthew 14:13-21). A penitent gaze, rather, would recognize that God fed Israel so Israel could feed others (Psalm 145:15), and realize that this is precisely what Jesus did with the 5,000. He didn’t erase God’s promise to Israel but, rather, participated in it—as had many Jews before him.

The difference between the supersessionist and penitent gaze is slim: Now you see it, now you don’t. But here’s a humble first step: Whatever we do with Matthew 14 — devotionally or homiletically — let’s locate Jesus more fully in God’s promise to Israel. In so doing, we start healing any overly decisive break between Old and New Testaments that our infected Christian imaginations harbor.

August 13

One More Step

1 Kings 19:9-18; Psalm 85:8-13; Romans 10:5-15; Matthew 14:22-33

ANOTHER SUPERSESSIONIST WAY that Christians read the Bible pits an Old Testament “God of fear” against a New Testament “God of love.” Even though this distinction has long been declared heretical (see Marcionism), versions of it persist today — particularly among progressive Christians. For example, when we cite Jesus’ embrace of the marginalized to combat contemporary forms of oppression without acknowledging his Jewishness, we can make it sound like the “God of love and acceptance” didn’t exist until the Common Era.

Similarly, a progressive supersessionist biblical hermeneutic often gets deployed to argue that we should no longer (that’s the supersessionist bit!) fear God. This week, this hermeneutic would supersede the supposed abusive God who desires our fear (Psalm 85:8-13) with the nonabusive Jesus who says, “Take courage! It is I. Don’t be afraid,” thereby calming fear with gentle love (Matthew 14:22-33). But, without the supersessionist interpretive turn, progressive Christians must deal more deeply with the biblical claim (which runs across both Christian testaments) that the God who calls us to repentance is a God who is actually terrifying.

Our penitent — rather than supersessionist — gaze lets the psalmist remind us that fear is the only response that can prove we’ve truly encountered God and that salvation only comes to those who have done so (Psalm 85:9). That the disciples, in Matthew 14, become afraid when they encounter the fullness of God’s glory in their friend is, therefore, a sign that they’re being saved (verses 25-26). Reading with an eye toward Jewish-Christian dialogue, then, I’m left wondering if it’s not just God’s wrath we fear, but also God’s love. And I’m wondering if this is a fear with which Jews and Christians could grapple together.

August 20

Paul Steps Forward

Isaiah 56:1, 6-8; Psalm 67; Romans 11:1-2a, 29-32; Matthew 15:10-28

THE REVISED COMMON LECTIONARY (RCL) tackles supersessionism head-on in Romans 11. After Paul’s opening remark — “Did God reject his people? By no means!” — the passage jumps from verse 2a, “God did not reject his people, whom he foreknew,” to verse 29, “for God’s gifts and call are irrevocable.” This jump isn’t duplicitous — lectionary editors trim passages all the time. More important, though, this editorial decision illuminates the chapter’s meaning in ways that a supersessionist reading would obscure.

Christians have weaponized against Jews much of what the lectionary editors jumped over. For example, the terminology of “the elect” is set against “the hardened” (verse 7) and the false dichotomy of God’s covenant with Israel being of law (or “works”) is pitted against the covenant with Christians being “by grace” (verse 6). When God uses Gentiles to make Israel “jealous” (verse 14), it’s too often presumed that all Jews have stomped off in a huff. But only a supersessionist Christian reading requires Jews who want to be included in God’s covenant to “exit and reenter” through Jesus. Paul, however, names no such requirement.

However, by limiting the poisonous uses of verses 2-28, the lectionary editors also limit the cure. For example, God pruning Israel’s tree and grafting the Gentiles into the remnant gets lost (verses 17-21). These verses that Christians have used to condemn Jews are also the ones that put Christians in our rightful place — even warning that we too could be pruned (verse 21). Is it time to stop minimizing risk and, instead, embrace it? Is that where our penitent gaze will lead next?

August 27

Less Impossible

Isaiah 51:1-6; Psalm 138; Romans 12:1-8; Matthew 16:13-20

I’VE ALWAYS HEARD Paul’s “many parts, one body” metaphor in Romans 12 as God’s delight in diverse community (verse 5). This past semester a small group of my students instead taught me that it’s the process by which such communities are forged that releases God’s transformative power.

Every other Friday, these five students and I squished into my office to talk about their ministry placements — conversations that required significant mutual vulnerability. When I saw who was going to be in the class, their identity dynamics looked like a pedagogical minefield: Two straight, theologically conservative, cisgender men — one older and white, the other younger and Black — and three younger students who identify with diverse queer and trans identities, two of whom were white (heavily tattooed) and one Black (clean-cut). But, as our group prayed, wept, broke bread, and even danced together, we became (as Paul promises) minsters, teachers, leaders, providers of compassion and cheer, and prophets in each other’s presence (see Romans 12:6-8). It wasn’t easy. The group worked hard and wrestled through a lot. Then, suddenly, it happened: many parts, one body. God transformed us into Christ’s body, complete with the flame of Christ’s Spirit descending.

Why am I telling this story here? Because I’ve been in too many contexts where a Christian desire to grapple deeply with supersessionism has led to an erasure of Jewish-Christian difference. “Christian Seder meals” are an extreme version of erasure. What my students reminded me, though, is that when it is truly God who is making us one, God will also preserve the dignity and difference of the many. And when that happens — well, I think that’s when the mysterious impossible finally becomes possible.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!