May 1, 2018

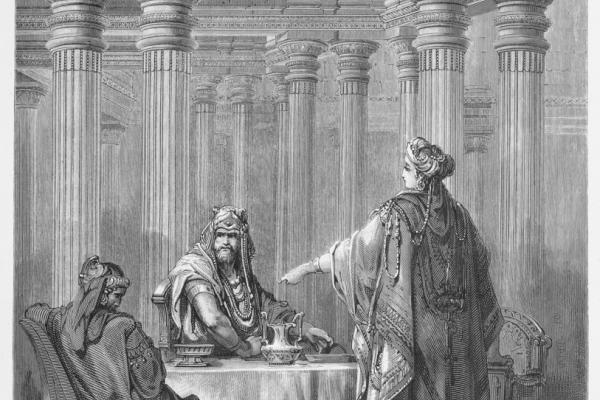

It’s not surprising that Christians don't relate to Zeresh. She’s one of the monsters, a biblical Lady Macbeth. But one group could stand to examine her character more fully.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login