Jan 25, 2022

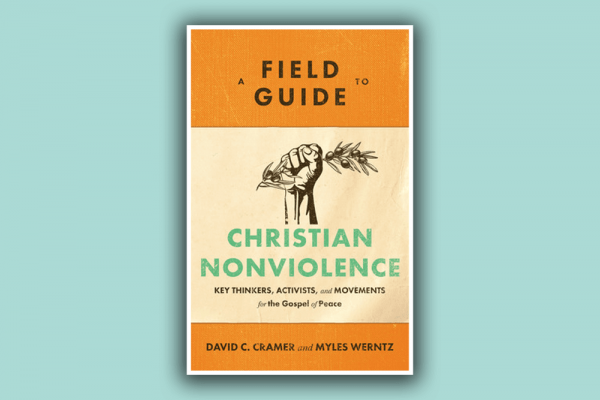

For most folks, Christian nonviolence evokes unified images of civil rights marches, Vietnam War resisters, and bumper stickers calling us to “turn the other cheek” or “beat swords into plowshares.” Yet Christian nonviolence isn’t a single school of thought, “but rather a rich conversation wrestling with what it means to live out the biblical call to justice amid the complexities of ever-changing political, social, and moral situations.”

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login