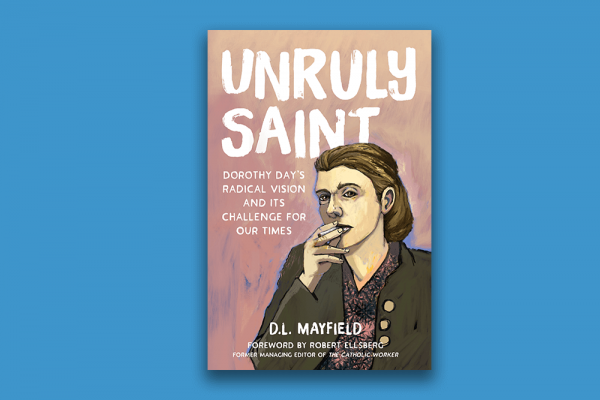

D.L. Mayfield begins Unruly Saint with a confession: “There are many excellent biographies of Dorothy Day already written. This book does not claim to be one of them.”

Instead, Unruly Saint is a personal, vulnerable, dynamic engagement with the life and words of Dorothy Day. Mayfield, who is neither a Catholic nor a historian, is someone who has “felt the long loneliness and [has] been both unsettled and comforted” by Day. Unruly Saint is a testimony to the challenge and solace of Day’s words in one writer-activist’s life as Mayfield processes her own tangled questions about God, loneliness, and how to love and live ethically in the world.

Mayfield discovered Day “in the thick of a personal crisis moment.” Mayfield was raised in the white evangelical church in the U.S., and as she began to ask questions about unjust systems in the country and the world, people within her community called her a heretic and made her an outcast. It was in her sadness, anger, and loneliness that she encountered the “smiling, stubborn, unruly saint” through a quote on a pin she was given at an event. The more she learned about Day, the less alone she felt. To Mayfield, Day is “a woman who carries a lantern for us lonely souls in our current chaotic and confusing time.”

The book follows Day’s life from her childhood in turn-of-the-century Chicago to her years as a radical in 1920s New York, her conversion to Catholicism, and the Catholic Worker years that began during the Great Depression. Mayfield includes stories about the people in Day’s life who made her who she is, including her daughter, Tamar, and her Catholic Worker cofounder, Peter Maurin.

While writing about the events of Day’s life, Mayfield depicts the inner emotional landscape of what Day was enduring, based on careful, between-the-lines readings of various accounts and journal entries: Day often wrote of the great joy of her conversion to Catholicism, but Mayfield points out that it was also a time of anxiety and heartache. People Day loved (including the love of her life and father of her child) left her because of it. The night of her baptism, “she went into the church alone and came out alone, a fact I think about often,” Mayfield writes.

God’s constant pursuit of Day, and Day’s longing for God, is the electric tremor that runs through the book. Day had always been “haunted—pursued—by God, and she felt this in her bones,” writes Mayfield. This tremor underscores everything Day does — it drives her to write, be in relationship with difficult people, and makes her believe in a world where everyone is taken care of and able to thrive. In writing about her conversion, Day “made it plain that God was with her in all the threads of her life,” Mayfield writes, “in all the tragedies and exultations, her yearning to be close to people in poverty and her urging others to change the world as soon as possible.”

Tamar, “often a silent and wide-eyed spectator” in the story of Day’s life, offers a lens into Day’s personality that “often get[s] overlooked by her biographers, the majority of whom are male,” Mayfield writes. Mayfield, as a mother herself, pays close attention to Tamar’s story. While Day lived a life of voluntary poverty, Tamar’s life of solidarity among the poor was “was chosen for her.” Tamar missed her mother painfully when she was on the road for so many weeks at a time. Tamar’s story, Mayfield writes, shows us “the downside of allowing one group to share all the burden of radical hospitality.”

One of my favorite chapters is about the “duty of delight,” Day’s spiritual ethic of noticing and appreciating small, everyday gifts of beauty. Day was “nourished by so many odd and beautiful things” — freshly rolled cigarettes, her black cat named Social Justice, the smell of perfume, a piano song, and Dostoyevsky books. These small things were “precious gift[s] to be savored, to give strength to the one who needs to get up and face the realities of the world again and again.”

Day is who Mayfield looks to when her soul is parched and she longs to be renewed with God’s love “in order to keep going.” I found Unruly Saint spiritually nourishing in this way: It wrestles with the questions of how we keep going, how we keep having hope in our exhausting world, how we keep our inner light burning. “She wanted to keep a flame lit for people wondering how to break the cycles of war and oppression built into our histories and hearts,” Mayfield writes.

Day criticized the church she loved throughout her life, calling out its hypocrisy and pushing it to do better. “Canonize me,” Mayfield imagines her saying. “And canonize everyone else too.”

At once contemplative and challenging, Unruly Saint is a lantern in the dark from one lonely soul to another across time. Perhaps, Mayfield points out, this is what it means for Day to be a saint — she is a disruptive friend, constantly nudging us to give our coats away, reminding us to “never stop asking why, and never stop hungering for God.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!