Jul 8, 2022

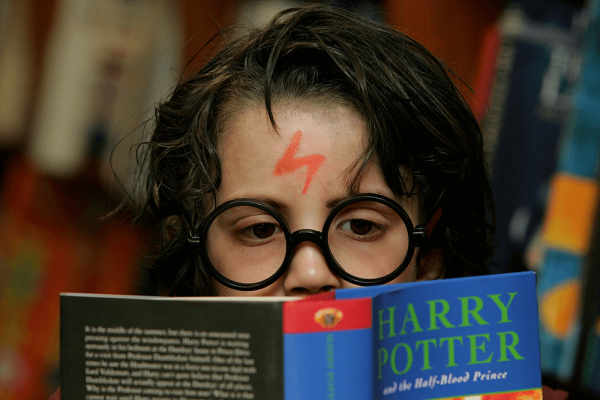

I was in elementary school when the first Harry Potter books were published in the United States. At the time, I was a painfully shy and awkward child; I treasured my library card and found solace in the stacks of books I carried home from our local branch. Though I was a prime target for a sensational new children’s book series, my parents — like the rest of our fundamentalist Baptist church — deemed anything about witchcraft inappropriate reading for good Christian children.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login