In the wake of the murders of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and George Floyd, a remarkable number of white people have joined the #BlackLivesMatter movement – even some evangelical Christian celebrities not known for making overt political statements. Joel Osteen, for example, participated in a #BLM march in his hometown of Houston to support the Floyd family. But Southern Baptist Convention President J.D. Greear has demonstrated a more tepid support, saying that while he believes that “Black lives matter” in a theoretical and apologetic way, he adamantly opposes #BlackLivesMatter as an organization due to its “liberal” causes.

Perhaps an article published by the Falkirk Center for Faith and Liberty best demonstrates this white evangelical opposition to #BlackLivesMatter. The conservative thinktank out of Liberty University argues that #BLM “is ostensibly built upon the pursuit of justice, but a different kind of ‘justice’ altogether than that laid out for us in Scripture. Not only is the organization deeply rooted in a false, cultural Marxist narrative, their secondary and tertiary goals are far more sinister than simply eradicating racism.”

Those goals, the article asserts, include the destruction of the “nuclear family,” supporting Planned Parenthood, and “the destruction of Western civilization as we know it” by rejecting “every godly value upon which our nation was founded.”

Although more politically conservative and evangelical voices are joining in the #BLM chants of “No Justice, No Peace,” there are undoubtedly shaky voices and (perhaps hostile) minds who hold that while Black lives do matter “in theory,” radical institutional change is far too dangerous and subversive, if not completely un-American. Other Christians, like Washington Times columnist Everett Piper, assert that saving souls and having more revivals, alter calls, and personal repentance experiences are the correct Christian responses to the current racial protests — not supporting a movement that Piper finds contradictory to the faith because of its ‘divisive’ rhetoric and encouragement of ‘harboring’ racial resentment.

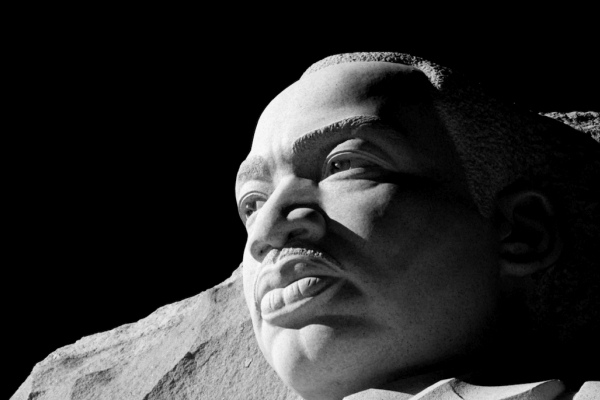

These key points of opposition ring strikingly similar to Christian opposition of another movement for racial justice: the civil rights movement. Many of the evangelical Christians who point to the civil rights movement, under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as the standard of dignified protesting, are the same Christians who oppose #BLM today.

The Black church was a pillar of the civil rights movement. It served as a resource hub for political mobilization, a meetinghouse for activists, and an incubator for developing the movement’s key leaders (including King, John Lewis, and Ralph Abernathy). Leaders across faith traditions, from Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel of Conservative Judaism to Archbishop Iakovos, the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church in the United States, walked hand-in-hand with King and supported the movement during a time when it was considered too radical for white faith leaders to do so.

White Mainline Protestant denominations and their faith leaders were generally readied theologically and politically to support King and the movement toward attaining civil rights for Black people because of their conviction that ushering the Kingdom of God included societal reform as a prerequisite.

Many other white faith leaders, however, were either silent or opposed to King and the civil rights movement, particularly white evangelical and fundamentalist leaders. At best, they saw the civil rights movement as a precursor to protests that could result in societal chaos and disorder. To them, the civil rights movement, and King specifically, were attempting to mend in society what faith alone could heal within an individual. At worst, however, they saw the movement as a ploy of communist opportunists and Soviet-Union sympathizers who sought to add discord to racial relations in tearing the fabric of godly, American society. One Southern, independent-Baptist preacher remarked in his sermon, after questioning the sincerity and nonviolent intentions of King and other civil rights leaders for their “left-wing associations”:

It is very obvious that the Communists, as they do in all parts of the world, are taking advantage of a tense situation in our land, and are exploiting every incident to bring about violence and bloodshed.

And he continued:

Preachers are not called to be politicians, but soul-winners.

This soul-winning preacher, hailing from a white, blue-collar family in the city of Lynchburg, Va., was a 31-year old minister named Jerry Falwell.

Falwell, like many other Southern fundamentalist preachers, was opposed not only to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, but to outright desegregation initiatives as well. Falwell was highly critical of the Supreme Court case that integrated public schools, Brown v. Board of Education, asserting that Chief Justice Earl Warren and the Supreme Court Justices were ignorant in knowing “the Lord’s will.” And according to Max Blumenthal of The Nation, Falwell was enlisted by J.Edgar Hoover of the FBI to spread FBI-compiled propaganda against King and the movement.

Prior to the Cold War, American fundamentalism arose as a reaction to modernism and the liberal theology rampant in mainline Protestantism that seemed to challenge long-held church teachings. The Platonic philosophical dualism found in the Pauline Epistles of the Bible — body vs. spirit, church vs. the world — reinforced their separatist beliefs. And their literal reading of the Bible, particularly passages in the Mosaic law that forbade the Israelites to intermarry with the ‘different tribes,” were utilized to paint racism as God-ordained and natural, and segregation as a political reflection of the Word of God.

The Communist Party USA’s support of the civil rights movement further alienated evangelicals from racial justice. The Cold War had made “Communism” the boogeyman of conservatives and mainstream culture, and certainly influenced how conservative Christian faith leaders would view a movement like the civil rights movement. (Bayard Rustin, a close advisor of King, was a former member of the Communist Party and openly “homosexual,” both reasons that forced civil rights leaders to keep him hidden and behind-the-scenes within the movement). This association with communism led many to see civil-rights activism as simultaneously subversive, un-American, and ultimately rooted in an infinite, ideological enmity.

The 1950s saw the United States equating ‘Judeo-Christian values’ with the sight and sound of The Star Spangled Banner, adding “under God’ in a Pledge of Allegiance that was originally written by a socialist minister, and adding “In God We Trust” on the dollar to implicitly affirm God’s approval on the laissez-faire market system by which America stands.

At that time, Falwell and his fellow fundamentalists believed religion and politics must be kept completely separate. It is unbecoming of a Christian to engage in worldly affairs, they rationaled, and heaven forbid one should engage in civil disobedience — a direct affront to the oft-quoted Romans 13 passage on "obeying the authorities of the land.” However, once Falwell saw the effectiveness of protests from the political Left in the’70s on Black Power, feminism, and gay rights, he changed his tune on political engagement and activism.

He apologized for his 1965 “Ministers and Marches” sermon that criticized the civil rights movement, and accepted the wave of America’s cultural tide toward racial-integration. It is noteworthy to point out that Falwell, along with Paul Weyrich and others who founded the Religious Right in 1979, were motivated to organize, in part, due to the federal government retracting tax exemptions on Christian schools that refused to admit Black people into their student bodies, which was to them a classic case of “state infringement on religious liberties.” Several years later, Falwell Sr. would invoke King’s legacy — swaying and singing “We Shall Overcome” with Alveda King (Martin Luther King Jr.’s niece and evangelical anti-abortion activist) at a Black church in Philadelphia where he decried the decisions and unrighteousness of liberal judges in the court system.

A young, Hollywood-looking, charismatic preacher named Billy Graham also had some thoughts on King and the rising tide in support for Black civil rights — this time from the evangelical perspective. A few days following King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Graham said:

Only when Christ comes again will the little white children of Alabama walk hand in hand with little Black children.

With those words, Graham dismissed the “I Have a Dream” speech. He rejected King’s aspirations for concrete civil-rights legislation in favor of a born-again, eschatological yearning for a racially brighter day across the metaphorical Jordan River upon one’s death.

In terms of theology, Graham and Falwell had much in common. Both believed in the divine inspiration and factual inerrancy of the Christian canon, both believed that eternal salvation from the fiery flames of hell was only possible in consciously accepting the idea of Jesus of Nazareth as one’s ‘personal’ lord and savior, and both stressed that societal change could only occur through an inward, individual transformation. The difference, however, and a notable difference that generally and historically marks an evangelical from a fundamentalist, is the former’s willingness to engage with the world outside one’s own.

Evangelicals (or neo-evangelicals) tended to be first or second generation fundamentalists who were educated in Bible schools and institutes, yet wanted their faith and culture to engage and not shun society. They took the Bible seriously, yet they also read the newspapers. They held a firm, unshakable faith in their convictions, yet carried a sense of dignity and decency in their interactions with non-believers. They came from the lower ring of the socio-economic spectrum, and their beliefs were dismissed as archaic by the religious and cultural elites, yet they desired public respectability. This was the Christian zeitgeist where Graham’s persona, convictions, and publicity instincts developed to help him become the darling and ideal of American evangelicalism even to today. This is also why American evangelicalism failed the civil rights movement.

Initially, a few mainline Protestant figures had high hopes for Graham’s ability to convince evangelicals and fundamentalists to push for civil rights. One theologian at Union Theological Seminary at the time, John C. Bennett, wrote that Graham was possibly the only person who could show “Bible-believing Christians” the implications of their faith on social matters, particularly on race relations. And to some extent, Graham did push the boundaries vis-a-vis the color line. He integrated his crusades, even personally cutting a cord dividing white and Black audiences at one of his events after one of his ushers refused to do so. And he reportedly bailed King out of jail after one of the civil rights marches. Though he agreed that desegregation was necessary, he also believed that a Christian shouldn’t break the law and engage in civil disobedience, much like similar voices today who eschew the tactics, protests, and rhetoric of the #BlackLivesMatter movement.

He then encouraged members of his denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention, to not participate in the civil rights marches. The last thing that America needed was more expansion of federal government power in combating what Graham believed was merely a personal moral failing of the individual(s). If racism was going to be combated, it had to be fought through the born-again experience, and the inner transformation that comes along with a Just-As-I-Am conversion.

Graham regretted deciding not to go to Selma and participate in the civil rights movement. When he received word that King had been killed, Graham was reported to have said, “I wish I had protested.”

King’s death created a paradigmatic-shift on white tolerance for racism. His assassination marked the moment where support for segregation was no longer culturally acceptable, and that overt racism was no longer welcomed in the public square. Graham’s regret perhaps is also the collective regret of many whites, including white evangelicals, today. The evangelicals were silent when King was alive, and they witnessed racism kill King at a bullet’s speed.

Perhaps this is why we see some whites performing awkward acts like washing the feet of Black clergy at a #BLM protest, or Chick-fil-A’s CEO Dan Cathy shining the shoes of Christian hip-hop artist Lecrae, or House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Democratic congressional leadership kneeling in silence while wearing Ghanaian kente fabric around their shoulders. To be seen in a humble stance in a public setting, especially in relation to a Black person, is an attempt at optical repentance — an attempt to perform a certain symbolic action, infused with rich meaning, to give the performer(s) some feeling of absolution. But symbols are only as good as the realities of which they represent.

Today, the media landscape often blurs the terms “fundamentalist” and “evangelical.” An individual who was once seen as a fundamentalist is now described as an evangelical, because the Religious Right has given fundamentalists a medium to not only engage with the world, but a golden opportunity to shape the very world it once isolated itself from in their own image.

Lately, many of these evangelical voices have stumbled in their conversations vis-à-vis race. Jerry Falwell Jr. is currently facing public scrutiny for the drain of Black members of Liberty University’s campus following his blackface-on-mask tweet. Evangelical megachurch pastor Louie Giglio’s “white blessings” framing on white privilege was an attempted hot-take that turned into a hot-mess. And Pentecostal megachurch pastor Rod Parsley implicitly made the founding fathers look like they might have also founded racial reconciliation.

But upon George Floyd’s death, Rod Parsley released a video statement about the state of racism in America, invoking Martin Luther King Jr.:

I remember standing on that balcony when we lost one of the greatest men that ever lived, taken by a racist’s bullet. I would to God that his anointing will be picked up. That someone will be mantled with that great anointing. That nonviolent heart of God reconciling, restoring, reaching out …

Quite a few evangelicals hold King as the standard bearer of civil rights activism, selectively uplifting pious quotes on love, nonviolence, and peace as a way to denounce #BlackLivesMatter. The irony of the prophet is that the prophet is usually only seen as a prophet in hindsight.

The Christians who oppose #BlackLivesMatter today are no different from the Christians who opposed King and the civil rights movement. Their blindness is an inherited racism that comes from the same theological streams — from the same nationalistic political mobilizing of the civil-rights era fundamentalists and evangelicals. Likely, several decades from now, these Christians will wish that they had marched with the #BlackLivesMatter activists — those who will one day be considered the civil rights leaders of our generation.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!