This interview is part of The Reconstruct, a weekly newsletter from Sojourners. In a world where so much needs to change, Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair. Subscribe here.

I’m going to let you in on a little secret: If you see a book about politics published in 2025, it’s very possible the world is different than what the author hoped for when they pitched it.

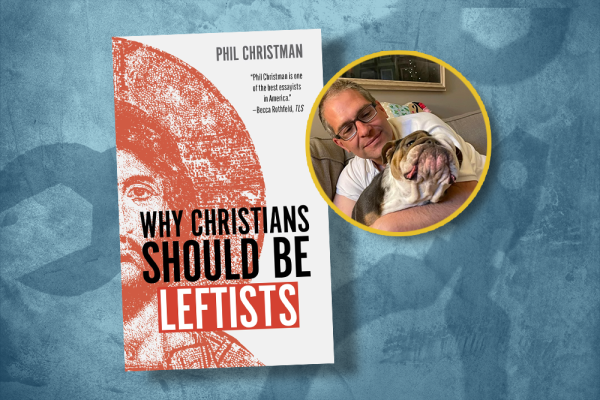

When I asked Phil Christman, author of Why Christians Should Be Leftists, whether he had thought he’d be publishing this new book under a President Kamala Harris, he looked at me with dismay and asked, “Is it that obvious?”

I quickly reassured him that it’s not obvious in any sense. I just happen to know about publishing schedules. His new book, out Sept. 16, must have been pitched well before the election. He was forthright; after the election, he took time to reassess a few sections.

“This book is aimed at Christians who have gotten off of the conservative Christian train in the last 20 years,” he said. The goal is to convince them to not stop the train at voting for Democrats, but instead to join leftists in a fight for a world where capital and violence don’t have outsized control in our societies.

Christman’s coal in the fire—or, more fittingly, solar power that energizes the eco-friendly train—is not a systematic theology or a polemic. Instead, it’s a testimony.

Chapter by chapter, Christman walks readers through his own faith story. He grew up in a fundamentalist household, making his way to the left under the guiding hand of Jesus, who preached that the “last shall be first,” not to hate losers and chastise the poor. He explains to readers why caring about neighbors necessitates caring about politics, economics, and even the labels we use to identify our politics.

In our interview, we discussed the concrete ways his faith impacts his leftist outlook, why the left and the church both need “moms,” praying for kings, and the CIA-endorsed list of “sins” that leftists and Christians all too regularly commit.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mitchell Atencio, Sojourners: I know authors rarely choose the title of their book, but “should” was an interesting word, rather than “can” or “must.” Instead of placing leftism as one option for Christians or insisting that Christians are only Christians if they are leftist, it says that Christianity should lead us to the left.

Phil Christman: Fundamentally, that’s just kind of what I think. The autobiographical portions of the book lay this out in more detail than I can do in an interview. But every time I’ve tried to take my faith seriously—live a life as right with God as I can manage it—I inevitably find myself acting in ways that are most legible to the world as forms of leftism.

These days, I’m bougie enough that I am tempted to become one of those white guys who just buys records 24/7. And to some extent, I yield to that temptation. But, instead of doing that, I try to throw a lot of my disposable income at people’s medical GoFundMes. I try to always have a fiver, a tenner, for random homeless people who ask me for money. Just everyday stuff like that.

As a leftist Christian, I have a lot of anxiety about the many coats in my closet, because John the Baptist said I only need one. And yet, I’m trying to update my wardrobe from cheaply made and poorly compensated items to clothes that will last, and that feels sort of bougie too. Are there areas where you feel caught in the structure of capitalism? How does that relate to the book?

Let’s ask the question like this: What difference does Christianity make for leftism? A common move at this point in the conversation would be for a leftist to say, “Well, Mitchell, there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism. We’re men of the world, we know this. Marxism isn’t about moralism; it’s about laws of history.” I’d make that conflict very abstract and impersonal.

As Christians, we don’t have that option. Because Jesus is always saying you. “You, you, you, you.” Jesus is concerned with the state of society, but he’s also concerned with the state of our souls. We should be concerned about what kind of people we’re shaping ourselves into; we may have to live with ourselves for a lot longer than three score and 10 years.

The personal consumption—that’s tough. Clothes? Anyone who looks at me every day knows that clothes are not the big temptation for me. I look like a person who is on the autism spectrum and can’t dress himself—which I, in fact, am. For me, it’s books, it’s records. [Author’s note: It’s also books and records for me.]

I’ve tried different approaches. It would be interesting to get into this in a follow-up book and try to think this out more systematically. I go through periods where I try self-imposed rules; the danger there is moralism, legalism.

READ MORE: Andrew Wilkes Is Convinced That the Gospel and Socialism Go Together

I go through periods of thinking “It’s not my library, these books are all going to go to someone else when I’m dead, I’m curating at most.” And I ask myself, because we’re not raising children, does this go to the Christian Study Center on campus? Do I make a point of willing everything to the U of M library? Do I make a point of willing everything to the library of a much poorer college that isn’t as snooty as U of M? That isn’t always giving yourself an excuse to buy stuff.

Probably the smartest thing to do, which I’m too disorganized to implement, is give yourself a hard number every month that immediately goes to charity. Pick a number that you feel safe with and then go higher than that. And then make all your spending decisions within a context where you’ve already shoveled the X amount out the door.

Maybe 10%.

Right! Start with the classics. At this point, I have a union job, and my wife has tenure. We should probably be starting out higher than 10%. And I haven’t sat down and counted it all out to make sure that’s the case. But that’s probably the move.

Something that I did not expect to show up in your book so much was the idea of moms. Your mom is at the front of the book, and you write about the category of moms toward the back of the book. Why were moms on your mind so much when you’re writing about why Christians should be leftists?

As soon as I deconstructed out of fundamentalism, but didn’t lose my faith, I had to start looking more seriously at my relationship with my mom and basically being nicer to her and taking her for granted less.

Part of trying to be a Christian has meant looking at the person in my intimate and family life who has often been a type of Christ—in that she is dealing with everyone’s garbage at once. It’s not just that patriarchy forces women into that position. Some, once forced into that position, try to imitate Christ in the way they live out that position. My mom is one of those.

Now, every time she steps into a voting booth, she does radical harm to the fabric of this country. She is in the tank for radical evil, electorally. And then, in terms of the way she treats the people in her life, she’s amazing.

I’ve also noticed how churches and left-wing organizations both have de facto “moms.” They have certain people—often women, but not always—who step up for the most boring tasks that there’s no glory in. The good mom is a type of Christ.

One of the ways that the world must be fundamentally reordered is that you shouldn’t be forced into the “mom” role because you’re a woman. More guys have got to embrace their inner mom! [Phil gestures toward Mitchell] They’ve got to do interviews for Sojourners while carrying their baby wrapped up on their chest.

And to take any hint of gender essentialism out of this, I talk about my best friend, the writer Adam Petty, [as a mom.] He’s been a stay-at-home dad for years. He has gone from being somebody who moved through the world as a free agent to being somebody who always has a bag with Band-Aids in it. We’ve all just got to get better at that.

Speaking of moms, are there things from your upbringing in a fundamentalist faith that moved you toward leftism or felt like a natural fit once you got there?

That was one of the things that I wanted to narrate and clarify in the book. One of my hopes for this book is that I could hand it to my people in my family and be like, “OK, this is why I actually thought I was listening to you guys when I reached all these conclusions that you completely reject.”

READ MORE: How My Conservative College Made Me a Leftist

It’s hard to see this as part of Christian fundamentalism today, because these days when I hear about Christian fundamentalism it means a church where they think the Sermon on the Mount is too woke. The actual biblical content has receded a certain amount. I don’t know how widespread that stuff is, but I know it exists. There’s an extraordinary moral slackness that goes along with that. Anybody who thinks that joining ICE can be an expression of their Christian identity is someone who’s just giving themselves excuse after excuse after excuse to do what they feel like doing.

But fundamentalism, as I experienced it, was constant agonizing about every choice you make. It was an extreme moral rigor. You know—feeling guilty that you thought a girl was cute, feeling conflicted about listening to heavy metal, scrupulosity about everything. Which can certainly become neurotic and can certainly be misapplied, but in general, I think we could all use a little more of that. Being some degree of morally serious and agonizing a little bit about how you live your life is very good.

On balance, I guess I would pick being raised in the fundamentalist version of that over internalizing the idea that it doesn’t matter what I do or how I live.

There’s an interesting point in the book where you talk about how there’s no biblical proof text that says, “Thou shalt run things democratically.” For a few years now I’ve been joking that the Bible tells us to pray for kings, and that I can’t be a biblical Christian if I’m not praying for a king.

The fundamentalists are trying to fix that for you.

Right. My curiosity becomes: Do we draw a political program from the Bible? You intentionally don’t settle debates between social democrats, socialists, anarchists, and communists and instead settle for a broad definition of “the left.”

To respond to the last part first, it’s important for readers to know there’s a reason the book has a very precise and also very vague title.

Christians should have a politics that, at the moment, usually means you default to voting Democrat. Better a possible eventual death from cancer than getting shot in the head right now. But we should be somewhere to the left of the Democratic Party. There are a million tendencies over there, and I do not make a call about which one.

I’m honest in the book that I have sort of instinctive, emotional preferences for some kind of social democracy, but I’m actually not sure that that goes far enough. If you leave anyone with hoarded economic power standing, they can pull that economic power to get rid of your social democracy. Something more like socialism might be the right place.

I also learn a lot from reading anarchists. I think their suspicion of the state forces them to use their imagination in ways that other people don’t. At the same time, I’m not always convinced by anarchists, because I think you’ve got to take seriously some of the reasons and situations that have caused people who weren’t rich to willingly opt for the state.

That tells you something about how specific a program I think we can draw from the Bible.

You are against any violence that is used to reify hierarchies and oppressions. The violence that is an attempt to escape from oppression, or self-defense, you seem a little less skeptical of. What do you understand Jesus to be saying when he says to turn the other cheek?

Turn the other cheek, go the extra mile, I think that’s prophetic hyperbole. The prophets will say, “The sun was darkened, life ended, and the world blew up.” What they mean is “Israel lost a battle” or “Israel split into two kingdoms.” Jesus is in that literary tradition. What Jesus is saying in those moments is, “OK, even if you’re fighting someone, don’t descend fully to their level. Don’t give back to them exactly as they’re giving you.”

If I joined ICE and became one of these marauding thugs in masks, and some kid comes at me with a knife with the intention of subduing me—not killing me—they are fulfilling Jesus’ command there. Because I’m trying to kill you, and you’re not trying to kill me.

But we are constrained to find ways to love our enemies. I do think that is binding. I don’t happen to be a member of the Peace Church traditions, but I think the Peace Churches are an example of the fact that Christ’s words are so fruitful that you can interpret them with a little too much literality or rigor and still wind up with something generative and beautiful.

Big picture, we should not be looking to do our enemies as dirty as they do us. I don’t know what that always looks like. I’m not getting down on my knees and praying for Trump’s salvation every day. Although, I don’t think that would be a bad idea.

What does it mean to do good to those that persecute you, which is also a thing that Christians are told to do? Politically speaking, what does that mean?

One thing it definitely means is pursuing policies that are actually good for everybody, even though that means you are helping out people who voted wrong the last 12 elections. You are aiming at a society that works for everybody, including people who opposed you and were your enemy.

In the book, you cite the Simple Sabotage Field Manual, written by the organization that preceded the CIA. It’s essentially a list of ways to obfuscate, delay, and nitpick a movement to death. You say that we should relate to it as a list of sins, repenting on each occasion we find ourselves committing one of the acts. One of the sins is, “Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions.”

Listen, I’m so glad you brought that up. Because to me, that’s one of the most important parts of the book, and nobody has mentioned it. It’s really funny that the CIA made this list of how to kneecap labor unions in post-fascist Greece, and it’s just a list of stuff that those on the left naturally do. I mean, probably sometimes someone doing it is a fed. But we just naturally do this stuff.

And every church committee flounders on the exact same behavior. It’s another one of those funny little parallels between Christians and leftists that I kept noting throughout the book. If you get nothing else from this book, please read that passage. And then don’t do any of those things.

My church met in high school gymnasiums for 12 years. We kept buying property and then selling that property, buying a different property, developing plans to build a church on that property, and then selling that property. When I was 15 or so—baptized and old enough to go to the church meetings—somebody complained that we’d been waiting eight years for a real church building. And I responded, “Israel wandered the desert for 40. I don’t know that we get to complain yet.” I don’t think I made a lot of friends as a 15-year-old being that pedantic in the meeting.

I would have shoved you into a locker. That’s amazing. Actually, there’s a point when I definitely would have been that kid too.

Christians should have a politics that, at the moment, usually means you default to voting Democrat ... But we should be somewhere to the left of the Democratic Party.

What difference does Christianity make for leftism?

I’m not getting down on my knees and praying for Trump’s salvation every day. Although, I don’t think that would be a bad idea.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!